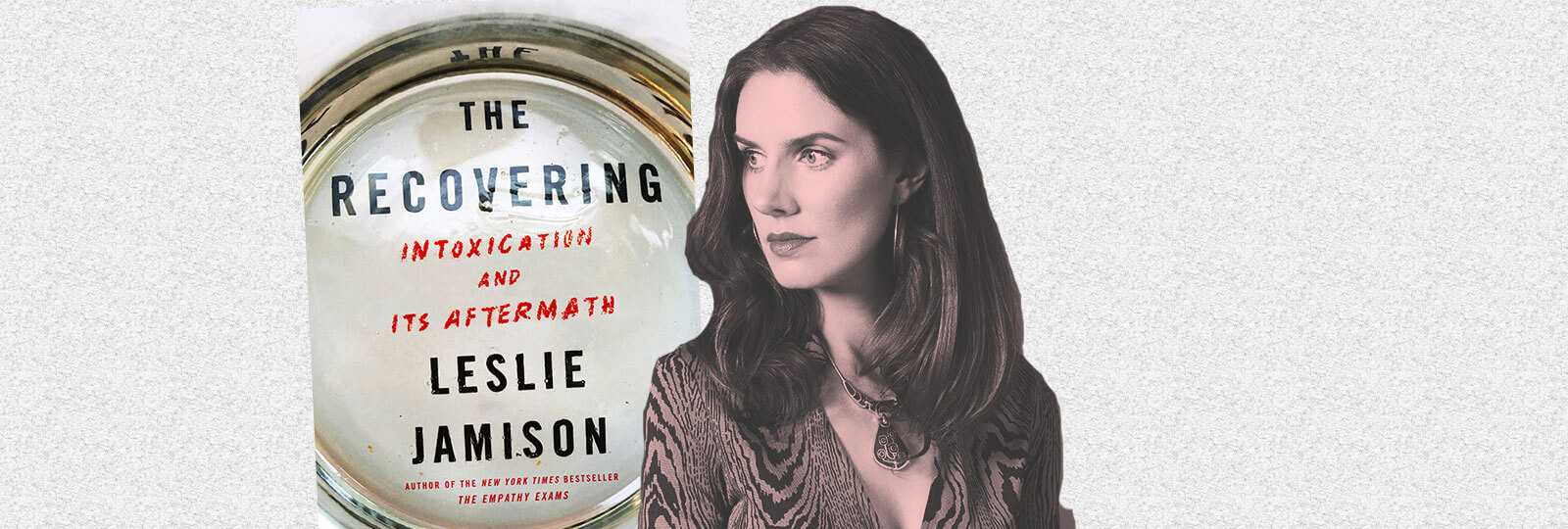

Beowulf Sheehan

Reading Women

Beowulf Sheehan

A Sobering Meeting With ‘The Recovering’ Author Leslie Jamison

The best-selling essayist of the 'Empathy Exams' talks with DAME about her deeply personal new literary memoir—a provocative meditation on addiction and recovery, and its impact on the creative process.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

When Leslie Jamison’s book of essays, The Empathy Exams, came out in 2014, it established her as one of the stars of a new wave of women writing nonfiction that felt urgently relevant. The essays blended personal writing and journalism; Jamison’s point of view was powerful and flexible, encompassing both an expansive humanity and a jeweler’s eye for the strange and unsettling. The title essay refers to one of Jamison’s graduate-school jobs, in which she tested medical students on their reactions to her simulated complaints.

In her new book, the memoir The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath, Jamison writes about her alcoholism (as well as disordered eating and self-cutting), set against a backdrop of a largely successful academic and professional life: Harvard, Yale, the Iowa Writers Workshop. At more than 500 pages, it’s longer and more literary than the typical addiction memoir, although there are passages in it you could find in nearly any drunk’s tale, as when Jamison shares this memory: “A year after my first AA meeting, I found myself drunk in a bathroom stall in Mexicali, snorting coke off the flat top of the toilet-paper dispenser.”

And that’s partly the book’s point: There’s a sameness to the story of addiction, just as there’s a sameness to the struggle of being human. For a writer trained to value individuality as a necessary part of genius, it took the long slog of AA meetings, at which personal stories are valued not because they’re original, but because they’re not, for Jamison to begin recovering.

The Recovering is a deeply personal narrative—Jamison chronicles both the risky choices she made while drunk and the searing shame she felt afterward—but its range is far greater than mere memoir. Much like Andrew Solomon did in The Noonday Demon, his book about depression, Jamison portrays the context in which her own story takes place. She also draws on her doctoral dissertation, which looked at alcoholic writers and what happened to their work after they got sober (or failed to, in the cases of Elizabeth Bishop and Jean Rhys). The result is both an immersive story and a provocative meditation on addiction and recovery, and how they intersect with ideas about creativity. Above all, it’s a book about learning to tell a different kind of story, one that embraces the humility of sobriety.

Clad in jeans and flannel, baby strapped to her chest, Jamison is as formidably intelligent in person as on the page, but she’s also down-to-earth. We talked in the Brooklyn apartment she shares with her husband, step-daughter, and newborn daughter.

You seem so sane and mentally healthy, which is not always what I might have gathered from reading your work. And especially in this book, there’s a sense that you’ve worked on yourself, and that you were really a mess. Do you still sometimes think of yourself as a mess?

Yes! I think, even in times when I really felt like a mess, one of my responses to feeling like a mess is to try to exert control over whatever I can. So, externally my life might not have looked as messy as it felt inside. One of the things that one of my sponsors in recovery said to me was that I would get in my own way, because I only felt comfortable articulating my emotional life once I felt like I could say it in some kind of cogent way.

You mention that moment in the book, the idea that you couldn’t just spew it out, you had to make it a clean enough story to tell.

I think that’s always meant that I presented as more together than I felt, because the narrative that I’m providing about my internal life is more polished than what the internal life feels like. So I think there’s a little bit of the messiness inside, that looks like something else once it makes its way into the world.

I always think that I live in a pretty different way than I did a decade ago. I think that my life is more about showing up for daily living now than it was then. I don’t have as much time to be so interior, or having a nonstop dialogue with my own feelings. Not that I never had things to do. I’ve always had jobs, usually more than one job, but just having an emotional life now that includes a lot of caregiving, it doesn’t leave as much room for the state of falling apart as there maybe used to be room for.

But some of the people you talk about meeting in recovery were in caregiving situations and still were really active, fucked-up addicts, so caregiving doesn’t save you from that. But I’m interested in the difference between interiority and then facing out. Is that something you thought about before you were in recovery?

One quick thought on the caregiving: I think you’re absolutely right, it doesn’t save you from anything. And certainly there are many people, and many people who I think are fantastic and very loving parents, who were also actively using for parts of their kids’ lives. And I know that in some way they got through those years … I do think sometimes, God, what would it be like if I were still drinking now? It’s kind of impossible for me to fathom. I have no doubt that I would have made it work, but I would have resented every moment of it. With my stepdaughter, I would have resented every bedtime that went late, because I would have been thinking, she goes to bed at 9, and after that I can really let it go. Not that there aren’t non-alcoholic versions of that! But just for me, I think the presence of the child would have been this obstacle standing between me and surrender. So I think about that a lot, this alternate world in which I was trying to live that life and this one. And it’s mind-boggling.

In terms of interior and exterior, I think it’s something that I thought about my whole life, but there was a certain framework or language for it in recovery that really resonated. That logic can be operative even if you’re not explicitly narrating it as such, like, why does friendship mean so much to me? A friend can engage with your life, but a friend can also save you from yourself, by being like, here’s my problem, and then you’re in their landscape for awhile. That was always like a form of salvation in my life, even when it was just happening inside of relationships. I think my writing has also been interested in that toggling between exteriority and interiority.

Yes! Your work in this book and in Empathy Exams spans personal essay and reporting, and then you also have a novel. As a student of writing and as a writer, do you ever assign like different mind states to the different forms that you work in?

The pieces in Empathy Exams, because I wrote them between 2006 and 2012, straddle my own recovery. I think recovery is one substructure of that book that’s never named. Part of it is that I feel like recovery really informed my relationship to reporting, and made me both more interested in formalizing and structuring the way that I was going to engage with other people’s lives as part of my work, and also helped me feel more comfortable doing that. At this point in my life I don’t identify as a shy person, but I did for many, many years. To commune with another person, hold eye contact with another person—all of those things were major character struggles for me! And recovery, among other things, you just spend a lot of time holding other people’s words. I think that did become both part of my desire for my writing life, and also a kind of strengthened capacity in my writing life.

But also, on a more philosophical level, it’s interesting to me the way some readers and writers experience a real cognitive dissonance around writing that tries to hold both personal narrative and other lives. It’s almost like trying to do both at once can make the personal feel like this invasive plant or something, like it’s taking up too much room or invading where it’s not supposed to be. Almost in this way where it’s like writing that has a first-person eye and other lives in it can seem more narcissistic or self-absorbed than just a straight personal essay or memoir, because somehow it’s like colonizing somebody else’s life. And that’s an interesting thing to me, because I can see the logic of it, but also part of what I loved about recovery is that it proposed a model of a kind of space where there wasn’t an antagonistic relationship between telling your own story and genuinely engaging with other people’s stories. There was room for a bunch of different “I”s in this room and those “I”s telling their respective stories isn’t about self-absorption—it’s an offering to the room, and there’s not that sense of finite real estate.

It’s also not a competition, like the one you describe in Iowa, with people trying to impress each other, to prove how charming they are, or what a great storyteller. The kind of stories that get told, and the way they get told, in the meetings that you write about attending, seem to work in a more reciprocal way: Everybody else is listening to your story as a way of holding you. And yet, you refer more than once to the telling as a kind of service. I’m curious about the parallels between meetings and writing workshops.

Especially nonfiction writing workshops! I wasn’t in a lot of nonfiction writing workshops as a student, but now I teach only nonfiction workshops. I think that part of the reason that my workshops feel different from other people’s workshops has to do with my experience in meetings. Not that I get the two things confused—I don’t think of a workshop as primarily a therapeutic space, or a recovery space—but I’ve seen what can happen when you make a space feel safe. That value of safety, and making people feel like their stories can come into a room and be held with compassion and grace, is absolutely something I’ve seen in meetings that I want to make happen in my classroom as a teacher. And so I do think that there are real resonances there.

I think there are just some basic human truths—like, how exposed you are when you share some part of your life, and what that means for what productive feedback would look like. All that said, I don’t essentially think that the metrics of literary value apply in a recovery meeting, nor do I think that the complete permissiveness I would bring to a recovery meting is the most useful way to come into a workshop. I think that if you’re writing stories for a public audience, as literary works, there are evaluative metrics that make sense. But there’s definitely a conversation between those two spaces for me.

At one point in the book, you mention one of the recovering writers you cover writing down things he overheard in AA meetings. Not that you would betray the trust of a meeting or replay its stories. But is there something about meetings that feeds you as a writer?

Yes! One of the ways it feeds my writing is that reminder that—not to sound cheesy, but that there’s a story in everyone, or really a thousand stories in everyone. There’s kind of a perpetual critique of personal writing that can follow the line of “too many people think their stories are worth telling,” and I guess implied in that is that there are only a limited number of people with stories worth telling—

And the rest of you really need to shut up!

Exactly! And I deeply disagree. It’s not like any story that ever gets told is equally good. But within any experience there are infinitudes, and you go to a meeting and you see that process enacted. You see 30 strangers walk into a room and any one of those strangers is someone you could have seen on the street or in the grocery store, and you would have no idea what was going on inside of them. And then you hear them speak, and you get some glimpse of what’s going on inside of them. And I feel like watching that happen over and over again is just this reminder that feeds both the personal writer in me and the reporter in me. It feeds the part of me that writes about my own life because it’s like, you’re not saying there’s anything special about your life when you write about it, you’re saying you are like any of these people who have something to say, and you’re trying to figure out how to say it. And it feels the reportorial self, because it’s like, right, any subject that I come across, if I’m doing my job right, I can try to figure out where the stories are in them, because I know that there are stories in them.

I’m curious about the idea, especially among book critics, that a memoir needs to have really high stakes, like that personal writing isn’t worth reading unless the stories are really explosive. There was a piece about you recently in New York magazine called “Where’s the Train Wreck?”—what do you think about that criticism?

I think that question, Where’s the train wreck?, is one that the book itself wants to wrestle with. Not only in the context of the literary marketplace, where I provide this reading of James Frey that isn’t meant to excuse him, but more of a projection of my own sympathetic impulses onto him, particularly around that question of wanting your story to be bigger. It gets back to that disconnect between the internal mess and the external composure: Sometimes I wanted the external mess to look more like a one-to-one correspondence with what it felt like inside. I think that was one of the ways I made sense of my eating disorder, as an attempt to make concrete and physical and undeniable what just felt nebulous, a set of internal feelings. And certainly it was a self-consciousness that I brought to meeting. I assumed that I would be judged at meetings. I was so struck by the fact that there was very little sense of “you don’t belong here, you haven’t lost enough,” and more a real desire to see the ways in which certain kinds of pain and longing and craving could be resonant across very different lives.

A lot of the book draws from the work you did on your dissertation, all of these threads following the writers in recovery. Did you approach their stories with some terror that that could be you?

Yes. But it felt really important to have recovery stories not just that weren’t successful in terms of people struggling to stay sober, but also where somebody might stay sober but that didn’t mean that everything got better. One of the payoffs for the structural mind-fuck and difficulty of having so many different threads in this book was the idea that it was a structural solution to the problem of imposing a kind of single narrative onto recovery, because essentially I’d given myself 15 different stories that were going to play out rather than just one. And that’s just a way to illustrate that there are a thousand ways this can go. It felt important to stay true to that by showing some of the harder ways that it can go, too. There’s something that’s always frightening about seeing what depression can do, and that the same kind of mental tumult that took you to substances can kind of creep up and destroy you like 15 years after you thought you were done with them. I think that there’s something also kind of anchoring about that fear. Recovery logic asks you not to think of your story as a closed story. It’s still ongoing. Alcoholism is not behind you.

That’s why people always say they’re a recovering alcoholic, always recovering, never recovered.

Yeah, and it’s why this book is called that, in part. There’s something tonic and useful about seeing myself as being in the same woods as these people, even if I don’t feel in the midst of a depression now. Not to conflate our lives, but to sort of feel a certain amount of humility around not knowing exactly where things will go, and not assuming all of the hard parts are done. That humility does hold some fear in it, but there’s something helpful and grounding in it, too.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.