Climate Crisis

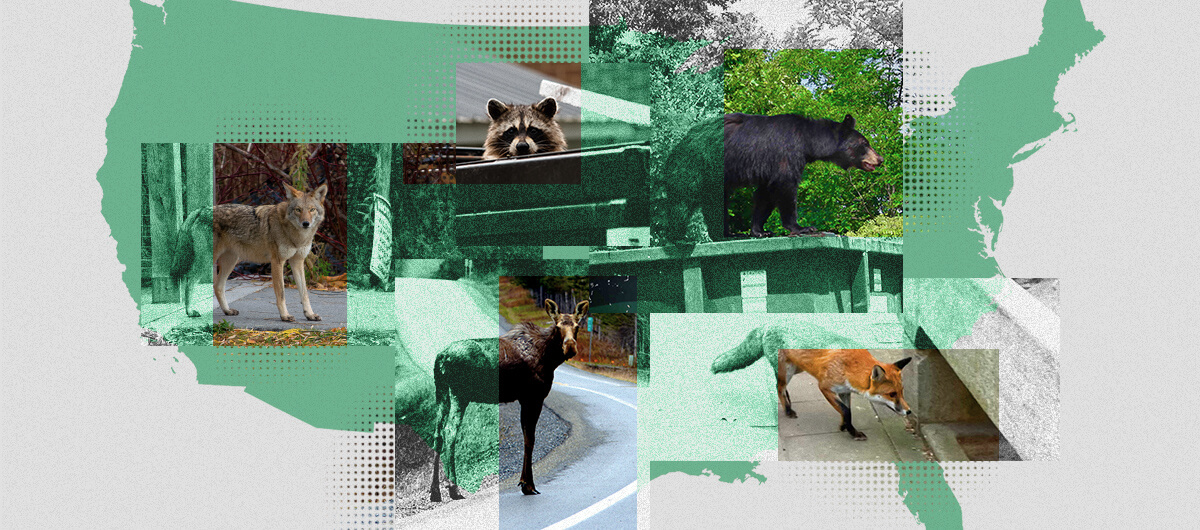

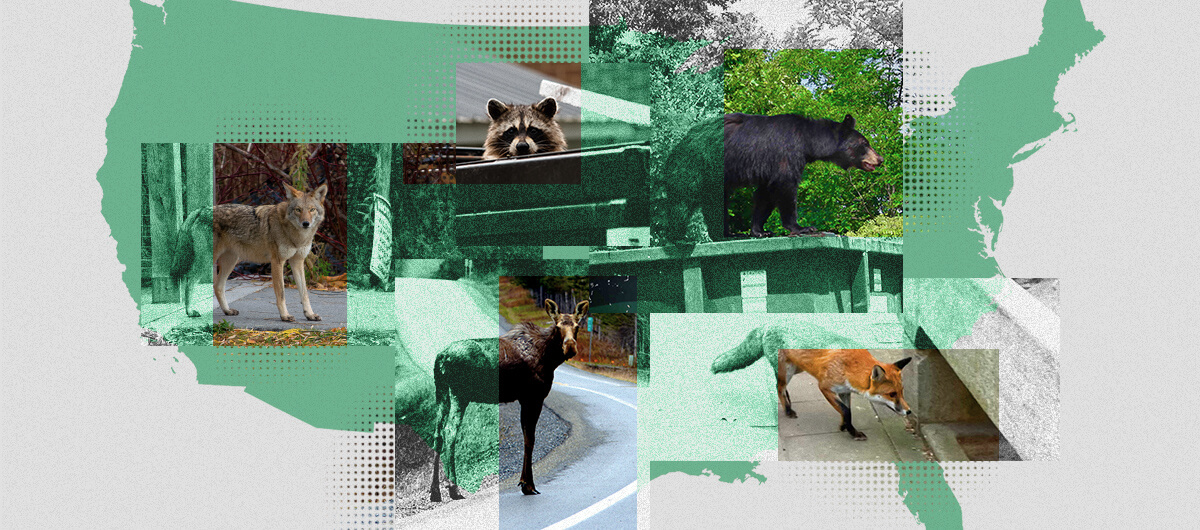

Sharing Is Caring: How We Give Back Land to Animals

Animals have been forced to adapt to people since we started messing up their land. To save them, it's time to reimagine the status quo.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Life in the early lockdown months of 2020 was slower, so much so that it became known as the “anthropause.” As people stayed home to combat the severity of Covid-19, a curious pattern emerged: Many became more aware of animals. Bobcats wandered along the Bronx River; people noticed birdsong. The earnest phrase “nature is healing” spread online.

In some ways, it did heal. Global air pollution levels dropped, and there was a quieting of noise pollution. In places like Florida, where closed beaches meant less trash and fewer sand castle obstructions, loggerhead turtles experienced a 39 percent increase in nesting success. But nature as a whole did not improve. Some animals struggled without the protections—and food—provided by tourists. Although lockdowns relaxed the fear certain animals, like mountain lions, have of urban spaces, wildlife-vehicle collision rates increased in the United States during the pandemic. “Nature is healing” became a meme.

Ultimately, analysis of the anthropause shows the temporary lockdown resulted in positive and negative effects on wildlife, contrary to the expectation that a natural world with less human interference would be better. To some scientists, this highlights how humans are both threats to and custodians of the environment. But it also underscores why a unifying theme has increasingly emerged in conversations over how to protect wild species and their habitats: coexistence.

Justine Smith is an assistant professor at the University of California, Davis and researches wildlife restoration and human-wildlife interactions. If humans on Earth suddenly disappeared, animal life would continue, muses Smith. But as we are here, we need to stay involved in efforts to protect wildlife because people will continue to interact with it. “A lot of the interventions that we need are to manage ongoing relationships with people,” Smith says.

She points to efforts to reintroduce grizzly bears to California as an example. The big question is not whether or not they can live in available habitats, it’s if they can coexist with the nearly 40 million people in the state.

Restoring the Human-Wildlife Balance

Over the last 10 years, there’s been a surge in studies focused on human-wildlife interactions and the concepts of coexistence, tolerance, and acceptance. But these aren’t new ideas: Some communities, including many Indigenous peoples, have long-established practices for living harmoniously with wildlife. It’s more so that certain institutions, like the U.S. government and mainstream science, are now paying attention. Research on some Indigenous techniques, for example, is now countering the Western belief that conservation requires the absence of people. Meanwhile, President Joe Biden’s 2021 America the Beautiful initiative aims to “conserve, connect, and restore” 30 percent of lands and waters in the U.S. by 2030, in part through these principles.

“I think we’re realizing, in the United States, that human use of landscapes is not going away,” Smith says. “So if we want to restore connectivity or increase the viability of wildlife populations, we have to start from that point because people will be there regardless.”

One of the core elements of the America the Beautiful initiative is the advancement of wildlife corridors. In April, the Department of the Interior announced a new round of funding for corridors in the American West. Wildlife corridors are connections across a landscape that link habitat areas and increase survival for many species. Corridors, alongside the reintroduction of mammals, have emerged as two powerful tools people can use to protect and sustain wildlife.

While these two techniques might look different, Smith describes them as related concepts that serve the same goal. “When you think about restoring wildlife populations, you can either do that actively or passively,” Smith says.

Reintroducing animals to a place they may have lived before, or need to live to survive climate change, is an active approach. Corridors are more of a passive process, where “you’re trying to let the animals move themselves into places where they can survive, given the environmental conditions that humans have created,” she explains.

Wildlife corridors are one focus of the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, a nonprofit located in Montana which supports projects that spur ecological connectivity. One ongoing initiative is the US-191 project, a possible corridor that could facilitate animal movement between Yellowstone and the Teton range. The hope is that an endeavor like this could help animals migrate despite growing tourism and development. It would also save lives: An assessment attached to the project found nearly a quarter of crashes reported on US-191 are due to wildlife.

The next steps involve evaluating what points in the road are most likely to facilitate safe crossing, what structures could enable this movement, and how human behavior may affect the process, explains Abigail Breuer, a senior program officer at the Center.

“For wildlife survival, movement is absolutely fundamental,” Breuer says. Further, conservation science suggests this connectivity is most likely to be successful if people buy in.

“We have to find a way for wildlife and people to coexist,” she says. “We can’t conserve it all.”

Coadapting to a Changing Environment

Further West, people are considering taking an active approach to sea otters. This means possibly reintroducing the animal to its historic range in northern California and Oregon. In the early 1700s, the worldwide population was at a minimum of 150,000 individuals. By 1911, after being hunted for their fur, there were fewer than 2,000 sea otters. The last wild sea otter in Oregon was killed in 1906.

But in 2020, Congress directed the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to assess the feasibility and costs of reintroducing sea otters to the Pacific Coast. The genesis of this idea was “the recognition of the critical keystone role that sea otters play in the nearshore marine environment,” says Michele Zwartjes, a field supervisor in the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office.

Sea otters help mitigate climate change by keeping sea urchin populations at bay. Sea urchins left unchecked decimate kelp forests—seagrass systems that assist with carbon capture. Zwartjes points to the ripple effect of the sea star wasting disease as an example of how out-of-balance parts of the Pacific Coast are. Even though northern California and Oregon lost sea otters long ago, sea stars kept the sea urchin population under control. But when the blight hit, the sea urchin population exploded, and “they just mowed down the kelp forest,” she says. The overall loss of biodiversity resulted in a less resilient ecosystem.

Zwartjes is part of a team that produced a recent report evaluating the feasibility of reintroducing sea otters to restore balance. It marks the early stage of a long process; moving forward would involve a legal evaluation, biological assessments, and an appraisal of the socio-economic impact. If reintroduction does move forward, there are two potential sources of animals that could repopulate the area: wild otters from other regions or released stranded pups reared by otters at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

The report found that reintroduction is “undoubtedly feasible… we know it can be successful,” she says. But what’s most uncertain is how the event would impact local communities and whether or not they’ll be on board. Some clearly will benefit: people who work in tourism and in fisheries. The Confederate Tribes of Siletz Indians already advocate for the return of the sea otters. But it’s possible people whose livelihoods depend on shellfish may not like the predator in their work range.

Stakeholder engagement is an aspect of reintroduction that is “every bit as important — if not more important — than the actual logistics and biological questions that go along with a reintroduction,” Zwartjes says. “Ultimately, if you don’t have that kind of engagement and support, it’s very unlikely that any reintroduction effort is going to be successful.”

This engagement — alongside these passive and active approaches to restoring wildlife — connects to a third key ingredient spotlighted by Smith: behavioral management. This refers to animals and people. Ecological projects are more likely to be fruitful if an animal’s behavior is factored in. For example, a wildlife corridor in California — which will be the world’s largest wildlife bridge when it’s completed in 2025 — is intended to help mountain lions. But anxiety over its success stems from asking whether or not the lions will actually use it.

Meanwhile, wildlife success is also more likely if human behavior is compatible. Killing predators is seen by some as a form of coexistence. But that action is clearly not conducive to the ecological aims of people seeking to restore biodiversity and mitigate climate change.

“We still have a fairly low tolerance for animals inconveniencing us in general,” Smith says. “There’s this idea that coexistence requires coadaptation. At the same time, the animals that are going to be able to coexist with us are going to be the ones that can coadapt to us as well.”

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.