Feminism

What White Women Should Learn From Fannie Lou Hamer

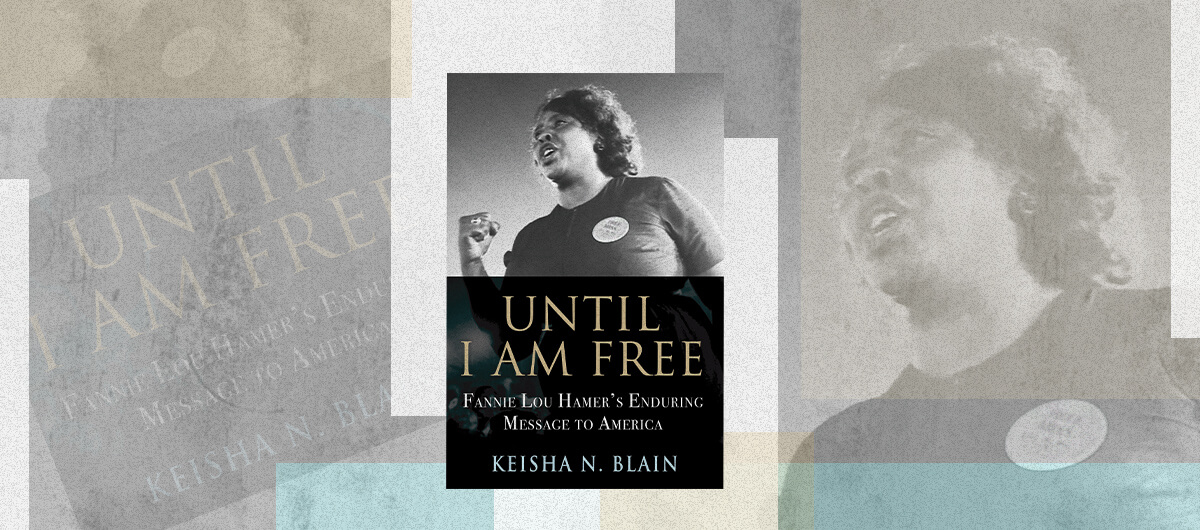

In this exclusive excerpt from 'Until I Am Free,' historian Keisha Blain shares the civil-rights activist's frustration with the women's liberation movement's erasure of Black feminists.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

In 1971, Fannie Lou Hamer delivered a powerful speech at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund Institute in New York City on the topic of women’s liberation. As she had done many times before, Hamer began by centering Black women and their experiences. She took the opportunity to emphasize that Black women’s lives are shaped by numerous hardships in American society, not solely gender oppression. “The special plight and the role of black women is not something that just happened three years ago. We’ve had a special plight for 350 years,” she began, alluding to the history of chattel slavery in the United States.

While her remarks were intended to offer insights into the experiences of the Black women too often erased from mainstream narratives, Hamer did not resist the urge to take a jab at the women’s liberation movement. By arguing that Black women’s plight was not new, or “something that just happened three years ago,” Hamer revealed her frustration with how public discussions on women’s rights and liberation framed the movement as unprecedented. While the women’s liberation movement certainly helped to raise greater awareness of gender inequality in American society, Hamer’s remarks served as a bitter reminder that Black women needed no such consciousness-raising; their daily experiences—as well as the experiences of generations of Black women who preceded them—had already revealed to them the nature of gender oppression. Along those lines, Hamer reminded audience members of her family history: “My grandmother had [a special plight]. My grandmother was a slave. She died in 1960. She was 136 years old. She died in [Mound] Bayou, Mississippi.”

Hamer went on to explain how she viewed liberation—a term that was central to the women’s rights movement of the period. “I work for the liberation of all people,” Hamer argued, “because when I liberate myself, I’m liberating other people.” White women were certainly included in this group. Hamer carefully explained the kind of liberation these women needed. It was a liberation from their own thinking and complicity:

“But you know, sometimes I really feel more sorrier for the white woman than I feel for ourselves because she been caught up in this thing, caught up feeling very special, and folks, I’m going to put it on the line, because my job is not to make people feel comfortable. You’ve been caught up in this thing because, you know, you worked my grandmother, and after that you worked my mother, and then finally you got hold of me. And you really thought, people—you might try and cool it now, but I been watching you, baby. You thought that you was more because you was a woman, and especially a white woman, you had this kind of angel feeling that you were untouchable. You know what? There’s nothing under the sun that made you believe that you was just like me, that under this white pigment of skin is red blood, just like under this black skin of mine. So we was used as black women over and over and over.”

Hamer’s remarks hit to the core of a fundamental problem with the women’s liberation movement: how the majority of white women failed to acknowledge their own privilege and investment in white supremacy. American society conferred a special status for white women, tracing back to the era of slavery. They were so “caught up in this thing,” as Hamer argued, that too many white women in the movement lacked introspection and failed to acknowledge the way they had long contributed to the oppression of other women. She turned to her own personal experiences to reinforce the point. “You know I remember a time when I was working around white people’s house,” Hamer noted, “and one thing that would make me mad as hell, after I would be done slaved all day long, this white woman would get on the phone, calling some of her friends, and said, ‘You know, I’m tired, because we have been working,’ and I said, ‘That’s a damn lie.’ You’re not used to that kind of language, honey, but I’m gone tell you where it’s at.”

In recounting this simple yet profound story, Hamer captured how interlocking systems of oppression—in this case, racism, sexism, and classism—shaped her life and the lives of other Black women. The domestic work of Black women in the intimate spaces of white people’s homes often brought these issues to the surface. Though Black women certainly shouldered the burden of sexism, it was by no means the only burden they carried. Hamer reminded white women that their race provided them freedom at the expense of Black women and other women of color: “So all of these things was happening because you had more. You had been put on a pedestal, and then not only put on a pedestal, but you had been put in something like [an] ivory castle.” If the women’s liberation movement removed the veil from many women’s eyes, then Hamer argued white women should have to glimpse the struggles Black women had encountered for decades. “[W]hen you hit the ground,” Hamer candidly explained, “you’re gone have to fight like hell, like we’ve been fighting all this time.”

It was a message of truth, difficult as it may have been for many white women to accept. But Hamer’s message made it clear that for all of the real challenges white women endured on account of gender oppression, they had not experienced the depth of oppression and mistreatment Black women endured in American society. White women’s position in society—as beneficiaries of whiteness and, often tacitly, white supremacy—afforded them more opportunities than Black women. Hamer therefore resisted any narrative that focused solely on gender oppression without a consideration of race oppression and class oppression.

Excerpted from Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America, by Keisha N. Blain. Copyright 2021. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press. (To purchase a copy, you can click on the link.)

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.