First Person

This Land Is Not Your Land. Or Mine.

The iconic Pete Seeger folk song has become an anthem for the predominantly white environmental movement. But can a colonized nation built on the backs of slaves ever really make that claim?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I remember it like it was yesterday: April 2017 in Washington, D.C., at the People’s Climate March. The first such march in 2014 had led throngs of more than 300,000 through the streets of New York City to the United Nations Plaza to demand climate action. This D.C. march was only slightly smaller, with about 200,000 participants, but there were many more at satellite marches across the country.

My co-worker Darnell called me over and whispered, “Are you seeing what I’m seeing?” As he gestured over the crowd, what I saw was blinding: a crowd of white faces as far as I could see, while Darnell and I were the only Black faces, and among only a handful of faces of color.

There was more color in the signs and the costumes.

At that point, I had been a Black person in green spaces for three years, so I wasn’t so much shocked as dismayed. In fact, my anticipation of this exact awkwardness had kept me from attending earlier environmental marches, including the inaugural 2014 event. I’m a Black woman from Birmingham, Alabama, and rural Mississippi, so I avoid large crowds of white people on pure instinct.

I’d been quite content to sit behind a desk and help other people with their signs and their talking points, thank you very much. But this year was different. Donald Trump was president and he was doing everything in his considerable power to erase any hope of a livable future.

Fuck my awkwardness. Fuck my fear of crowds. It was time to show up.

So we marched on because—damn it—this is our planet, too. Darnell and I are both aware that while climate change may be an equal opportunity destroyer, our society is structurally racist to its bones. In the event that there can be sacrificial lambs, those lambs will look a lot like us—if they aren’t us ourselves. In other words, the burdens fall heaviest on the people already structurally situated to be least able to carry them.

As we neared the White House, I heard the familiar song that made my shoulders shoot up, cringing:

“This land is your land. This land is my land…”

Legendary folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote that iconic song in 1940 while traveling the length and breadth of the country. Through his travels, he became both enamored of the beauty of the landscape and frustrated by the Depression-era income inequality. It was meant as a populist response to “God Bless America,” which dominated the radio waves at the time.

But this song makes my stomach ache. As it entered my ears, my face—hyper-emotive to a fault—contorted into knots. I walked a little faster and tried to keep my eyes focused on the road. I saw a woman to my right eyeing me with concern. Despite my fervent (but silent) protests, she made her way over to me and shared her lyric sheet with me. Of course, she thought I didn’t know the words. Of course, she thought I looked out of place.

I summoned all the manners I had been raised with to say, “No, thank you,” but my grimace was irrepressible, and so I moved away as quickly as I could. Because what I wanted to tell her was that this land is not her land. It’s not mine either. And it never was.

The song, first recorded in 1944 in New York City, was not released on the radio until 1951, by which time the economic woes of the Depression had largely eased. The song was performed by schoolchildren and even used in car and airline advertisements. It didn’t make a comeback as a protest song until the 1960s.

Granted, some verses are more protest-oriented than others, and those verses were nearly lost until the 1990s. But none of those verses acknowledges the country’s genocidal history of colonialism and slavery. In other words, there is not a single verse that I, as a Black woman, can relate to, not one that speaks to my experience nor my complicated relationship to the land on which I stand.

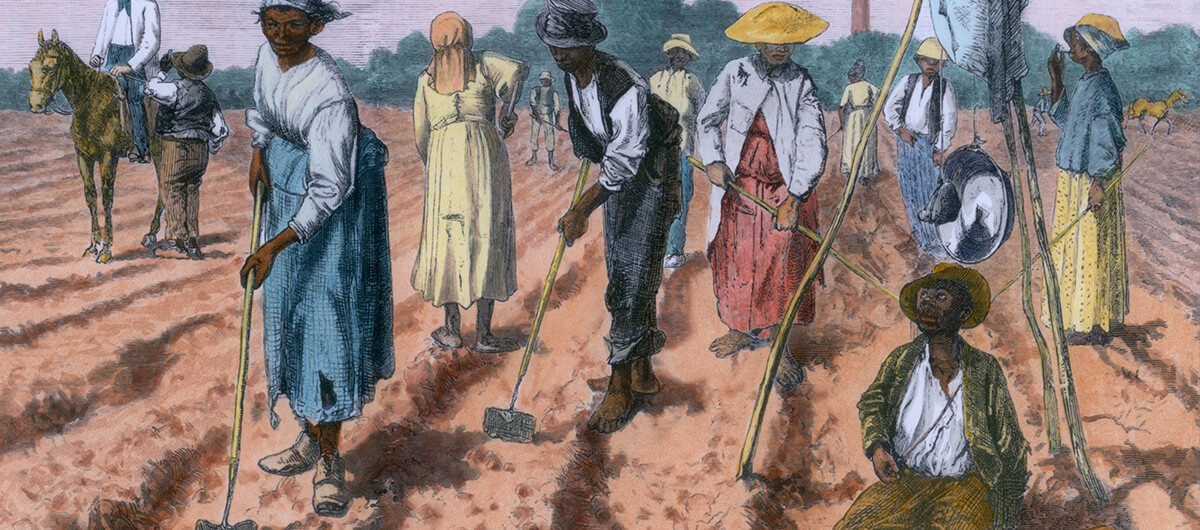

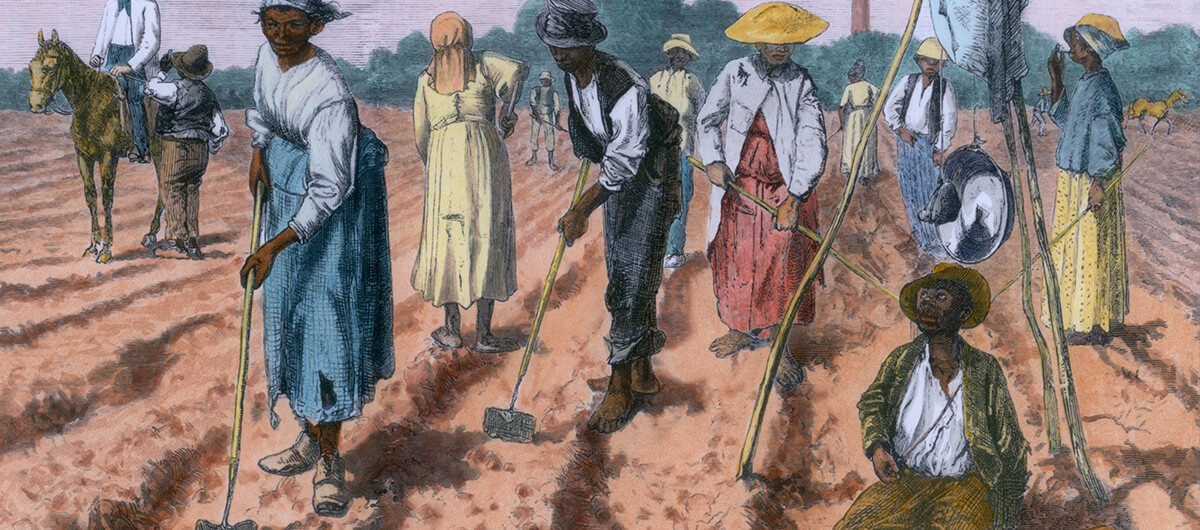

This country was built on the backs of Black people. But the United States of America has never belonged to us. Our relationship to this soil began with kidnapping, bondage, and torture. For centuries. Follow that up with yet another century of codified terrorism, most of which was either officially legal on the books or illegal in name only. And here we are today, when the school-to-prison pipeline remains strong, the wage gap is growing wider, and simply saying that our lives matter is seen as an act of aggression. The right to vote—the very baseline for citizenship—wasn’t afforded to us until 1965. A cool 100 years after the “end” of slavery. And even today, that right teeters on and off of life support. Ask Stacey Abrams.

So, no, America is not mine. She’s made that very clear. Not to mention, the idea of land belonging to me is quite alien to me. Sure, I feel a kinship to this land, but never a sense of ownership.

The Black community is not alone in this. America has thrown Japanese Americans in internment camps. Just recently, in a move reminiscent of the Chinese Exclusion Act of the 1800s, it instituted a “Muslim ban” that shamelessly targets Arab countries, ripping families apart literally mid-air. And, speaking of ripping families apart, we need to look no further than the ongoing cruelty at the Southern Border. Meanwhile, hate crimes continue to rise and three-fifths of them are motivated by race.

How is this song supposed to sound to Indigenous communities, whose very existence is an act of profound resistance to the colonial sentiment of those lyrics? For one thing, we know now that their genocide at the hands of European settlers literally changed the climate. For another, the Dakota Access Pipeline and Keystone XL pipeline fights are just part of a larger system of dispossession. Just last month, the government took its sweet time responding to severe, abnormal flooding at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

In 1968, the same year the Voting Rights Act was passed, Lakota Sioux Chief Henry Crow Dog pointed out the colonial overtones in “This Land is Your Land” to folk singer Pete Seeger, who then commissioned a new verse from an Indigenous perspective: “This land was stole by you from me.”

But that’s still not a verse I can sing. I didn’t steal this land, and it wasn’t stolen from me. And had the land not been stolen, we probably wouldn’t need this march.

In a lot of ways, “This Land Is Your Land” and its colorblindness are indicative of the problem within the larger environmental movement, which can trace its roots back to the conservation movement of the 1900s. And that movement was steeped in oh-shit racism. Its founding fathers were just as passionate about eugenics and controlling women’s reproductive rights as they were about preserving the environment. For them, it was less about protecting nature than it was about laying claim to it—for people who looked like them. It should come as no surprise then, that the authors of conservation were also the authors of the aforementioned Chinese Exclusion Act.

In today’s environmental movement, it’s not so much outright hostility toward people of color. It’s more that people of color represent a blind spot for the environmental movement. White people don’t stop to think, for example, how this song sounds to… people who don’t look like them. We are an afterthought. And how can you care about someone you literally refuse to see?

That color blindness is as crippling for the movement as a whole as it is alienating to people of color. By ignoring our stories and our struggles, the environmental movement becomes divorced from the parallels to other movements for justice—including the Civil Rights Movement, where freedom songs were paramount—and unable to learn from the past. For example, it doesn’t notice that the very same people who criticize Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s environmentalism because she rides in cars sometimes are also the same people who say that blue lives matter,” to discredit the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s the exact same playbook of bad faith arguments.

These connections are as blinding to me as the whiteness of that crowd. And that’s why I know that this movement needs me, needs every one of us, as much as we all need a planet to live on. But, like 16-year-old climate activist and daughter of Ilhan Omar Isra Hirsi, I want to march with more people who look like me.

You know what would be a big step in that direction? Ditching a song that so blatantly ignores our existence.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.