LGBTQ

The Language of Gender

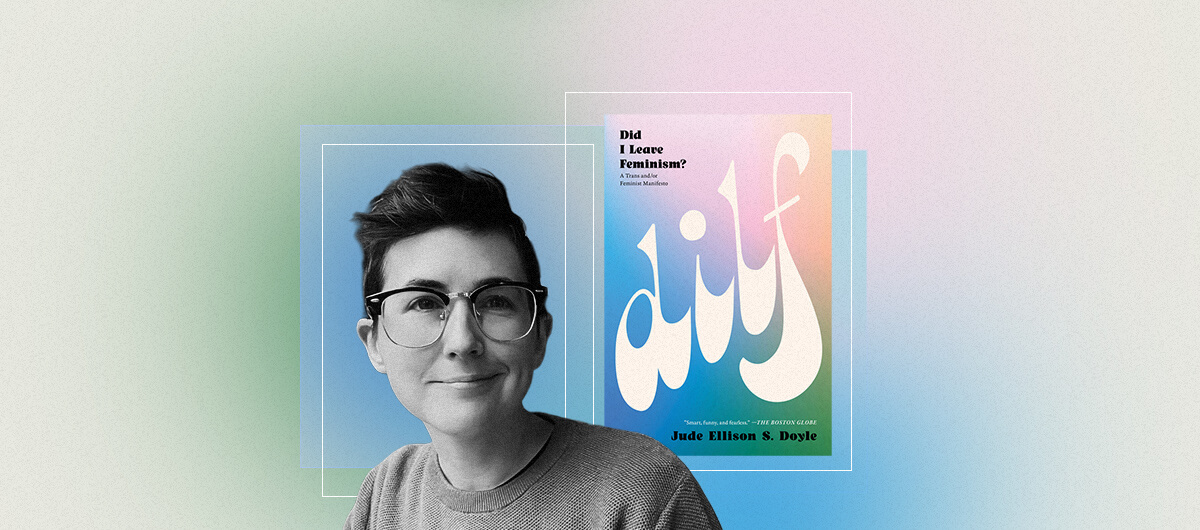

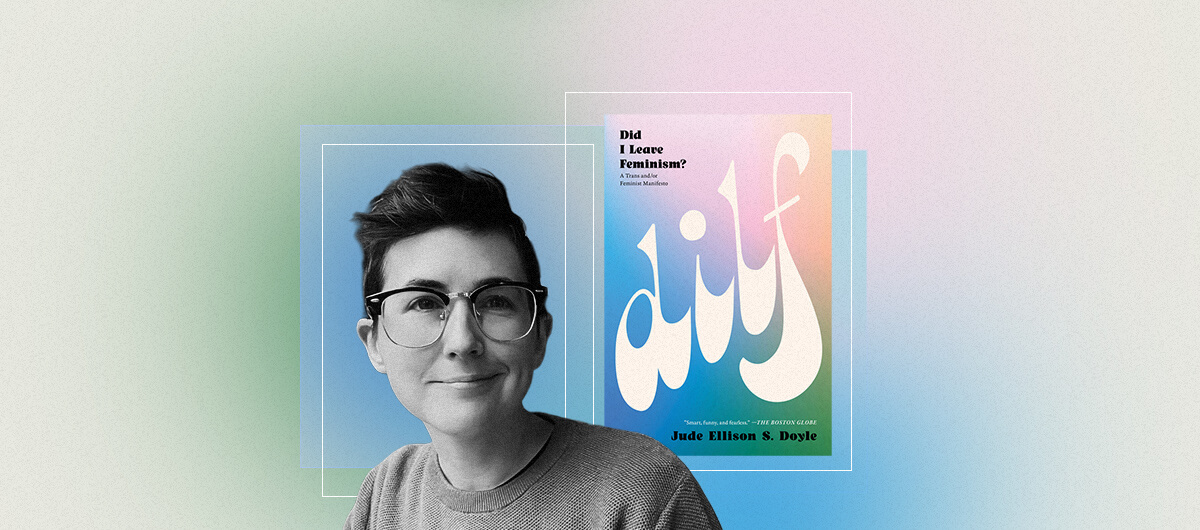

When he transitioned five years ago, our former "All the Rage" columnist Jude Doyle discovered just how much we all — cis and trans people — play dress-up with our gender presentation, which he explains in this exclusive excerpt from his new book, 'DILF.'

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Gender is not just a personal experience. It’s a social phenomenon. It’s not enough to know you are a man or a woman; other people must also know this about you, and in order to make that happen, you need to communicate your gender to the world.

The traditional conception of trans people doesn’t go any further than this: Trans people are people who dress up in the “wrong” gender’s signifiers. This is why transphobic commentators often accuse trans people of confusing gender stereotypes with gender identities — thinking that wearing lipstick is the same thing as being female, or that liking soccer is the same thing as being a boy. “‘Woman’ is not a costume,” quoth J.K. Rowling.

Of course, the world contains lipstick-wearing men and soccer-playing women; The Cure frontman Robert Smith and former soccer player Megan Rapinoe are not unknown to my people. For that matter, there are plenty of cis people with exaggerated or stereotypical gender presentations: Clint Eastwood, Marilyn Monroe, female ballerinas, male NFL quarterbacks, etc. Yet transgender presentations receive extra scrutiny, often a cruelly double-edged variety: If trans people conform to traditional gender norms, we’re “reinforcing stereotypes.” If trans people are gender nonconforming — and many of us are — then we’re “not passing,” which makes us freaks. At all times, the assumption is that we are playing dress-up, imitating cis people, who set the standards for what is real.

Yet everyone is playing dress-up in their gender, whether they are trans or not. Even if “woman” is not a costume, you have to wear the right costume in order for people to know that you’re a woman. As a culture, we have an array of signs and symbols and, yes, stereotypes that signify gender, and we have to incorporate them into our presentations — not because those symbols and stereotypes are objectively true, but because, otherwise, people won’t be able to guess what gender we’re trying to put across.

I will show you what I mean. Take a moment, right now, and draw two stick figures. Make one of them male and one of them female. Do it on the side of the page, on the cover, on a notepad, whatever you can get your hands on, but don’t read anything else until you’re finished drawing. Got it?

Now: If you are like most people, your “female” stick figure has a little skirt, and maybe long hair, if you’re feeling crafty. Your male stick figure has been allowed to rest comfortably bald and nude — given the vagaries of stick figure fashion, we can never be sure he’s not wearing pants.

Of course, you know that not all women wear skirts, just as you know there are men with long hair. You didn’t draw your stick figures this way because you’re a hardened misogynist, you did it because symbols are less complex than reality. Long hair is not a woman, but long hair means woman in the language of gender.

It’s true that our ideas of what “men” look like tend to change over the years. In 17th-century France, you could identify a manly man by his high heels, silken tights, and long, flowing curls; in 1980s America, hypermasculine hair-metal bands wore lip gloss and glitter eye shadow. Behavioral standards change: “Boys don’t cry,” for example, is a new one. In The Iliad, Greek and Trojan soldiers alternate between dismembering each other and breaking down into messy, public tears. I was taught that straight men should never touch each other — even in a movie theater, you had to leave an empty seat between you and your bro, lest you brush hands and accidentally become gay in the middle of Saw 7. In parts of the Middle East, I’m told, male friends often casually hold hands while walking down the street, and there are no sexual connotations.

But you’re not trying to pass as a 17th-century aristocrat or a member of Whitesnake, are you? You’re trying to use the men’s room in a Target without being kicked out. Thankfully, you and everyone else in that men’s room already share an idea of what a “man’s” haircut and or a “man’s” outfit looks like, one so simple and widely shared that you can take it more or less for granted.

This is gender as a language: Not an eternal truth, or an essential quality, but something you can use to communicate with the world.

This might seem low-stakes or frivolous: What kind of feminist spends a whole section of a book defining appropriate hairstyles? However, knowing your society’s acceptable gender expressions can be a matter of life and death. The boundaries of gender are patrolled with violence, and the more obviously gender nonconforming you are, the higher your risk. Trans people often obsess over the finer details of gender signaling — how you use your hands, how you stand, who you make eye contact with, how you pitch your voice at the end of sentences — because being able to clearly and accurately convey our gender, and fulfill other people’s gendered expectations, is what keeps us safe.

An example: I was going through a maze recently with my 6-year-old daughter. She got away from me, and I sped up to catch her. As I rounded a corner, I nearly bumped into a woman — about my own age, a little bit shorter than me — who recoiled away from me so hard she hit the opposite wall, clutched her chest, and, pointing me out to her companion, gasped, “This guy!”

This is a pretty common experience for trans guys: We don’t fully realize that we look like cis men until women start reacting to us like we’re Jason Voorhees. Now, I mean this woman no harm, but in order to communicate that, I need to be fluent in gender.

I know, for instance, that many women experience real fear when a man intrudes on their personal space, and that some women carry terrible memories; she’s not overreacting, and being surprised by “some lady” probably wouldn’t provoke the same reaction. She may already be mentally rehearsing her set of responses to a dangerous man, trying to figure out how to repel me without getting hurt. I also know that this situation is dangerous for me — cis women are just as likely as cis men to be transphobic, and to enforce their transphobia with violence. (Consider the infamous “bathroom problem,” wherein butch women are routinely harassed or accosted for using the women’s restroom.) If this woman realizes I’m trans, her fear could result in me being assaulted or kicked out before I find my kid.

For both of us, reestablishing safety relies on finding some quick and obvious way to signify that I am not a threat. This is not as easy as you’d think. Certain responses that would have read as comforting or maternal prior to my transition — reaching out a hand to steady her, calling her “hon” when I ask if she’s okay — would come across as intrusive or scary now. Thus, I decide not to prolong our interaction, but to simply demonstrate respect for her space, which I do by saying “sorry,” backing up, and giving her a wide berth as she walks past me. I look at the ground to avoid making eye contact. I hold my hands up, so she can see them, the entire time.

I don’t think it’s wildly sexist for me to acknowledge the realities of male violence, or to take those realities into account when being polite to strangers. I also don’t think it’s anti-feminist to minimize my own odds of being attacked. To accomplish either of those things, though, I have to refer to an internal Rolodex of stereotypes, both the ones I want to abide by (men don’t touch strangers; men don’t use terms of endearment without sexual intent) and the ones I want to defy (men are predators; men are bullies; men careen through the world like circus elephants that have snapped their tethers, trampling all in their path; and so on).

If this is still hard to swallow, consider that we signal our identities on many fronts, not just gender. Take another look at your bald, nude stick man: What sort of man is he, this hairless enigma? Is he an artist? A chef? Is he, perhaps, the Judge from Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, for whom baldness and nudity — along with a profound and ageless evil that represents, I think, American imperialism — are the defining parts of his presentation? There’s simply no way to tell under the present conditions. So, if you don’t want your stick man to stand for all the depravity of conquest, you had better draw a little firefighter’s hat on him and fix him in some more noble profession.

“Woman” is a costume. “Man” is a costume. “Firefighter” is a costume. We are all constantly calibrating our presentations to show the world who we are, or who we want to be. Yet, when we do it with gender, people get anxious. The question I want to answer is why.

From DILF: Did I Leave Feminism? Used with permission of the publisher, Melville House Publishing. Copyright © 2025 by Jude Ellison S. Doyle. You can purchase the book here.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.