Author photo: Stanton J. Stevens

Q&A

Author photo: Stanton J. Stevens

Can We Love Art Created by Loathsome People?

In this in-depth interview, Andi Zeisler sits down with Claire Dederer, the author of the brilliant new book ‘Monsters,’ about the ethics of consuming art by people we have come to know as monstrous.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I’m probably not the only woman who, in November 2017, clicked on the link to Claire Dederer’s Paris Review essay “What Do We Do With the Art of Monstrous Men?” hoping that it might offer, well, an answer. The piece had splashed down into the furious churn of media chronicling the global #MeToo reckoning, but the question was a new and far blunter version of a queasy little voice that had interrupted me for years, barging in on my enjoyment of music and literature and underground comics like a vaporous docent to ask Why do you love this thing that hates you?

As it turns out, there was no answer, only more questions. Questions about the ethics of consuming—of wanting to consume—the art of people we know to be monstrous (“Do we vote with our wallets? If so, is it okay to stream, say, a Roman Polanski movie for free? Can we, um, watch it at a friend’s house?”). Questions about whether an inability to separate the art and the artist is an objective failing (Which of us is seeing more clearly? The one who had the ability—some might say the privilege—to remain untroubled by the filmmaker’s attitudes toward females and history with girls? Or the one who couldn’t help but notice the antipathies and urges that seemed to animate the project?”). Questions about whether monstrousness might, in fact, be a necessary part of making art in the first place. (“The critic Walter Benjamin said: ‘At the base of every major work of art is a pile of barbarism.’ My own work could hardly be called major, but I do wonder: at the base of every minor work of art, is there a, you know, smaller pile of barbarism?”)

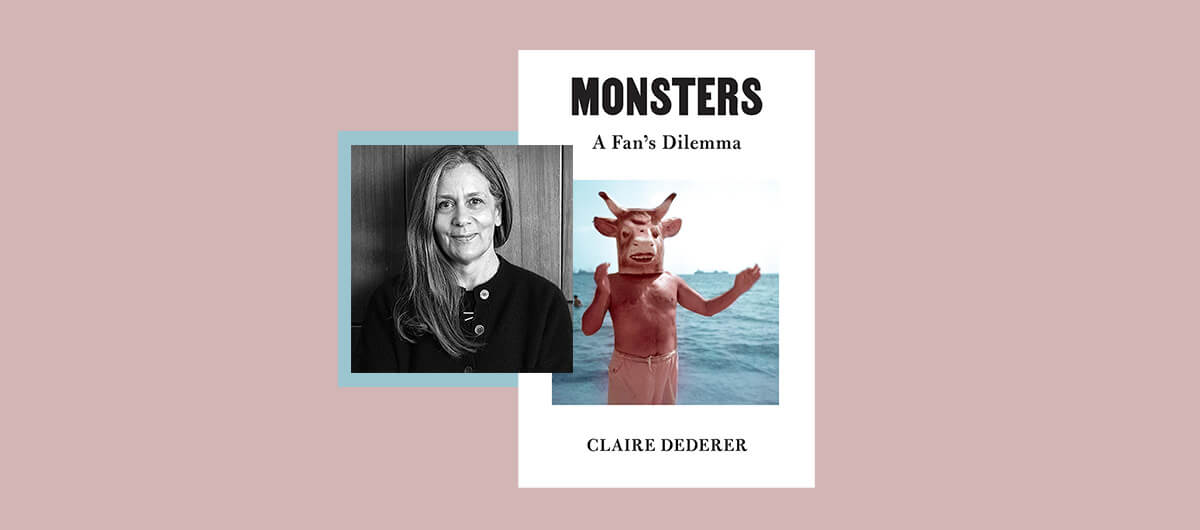

Dederer, the author of Poser: My Life in Twenty-Three Yoga Poses (2010), and Love and Trouble: A Midlife Reckoning (2017), builds on those questions in Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, a relentless and exhilarating tussle with history, idolatry, and selfhood. In 13 chapters that probe the complexities and contradictions of art, audience, critique, and condemnation, she examines the lives of artists whose monstrousness is inseparable from their art (Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, Richard Wagner) as well as those whose determination to create rendered them monstrous (Doris Lessing, Joni Mitchell), grappling with indelibly gendered beliefs about art and nurturance. In considering the critical shibboleth that demands we “separate the art from the artist,” she challenges the historical idea of a universal authoritative lens.

The moment I finished reading Monsters, I wanted nothing more than to talk with its witty and constantly questioning author. With my wish granted, here is how that conversation went.

Monsters grew out of an essay you published in The Paris Review, “What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?” Back then, you’d revealed that you were working on a book about “the relationship between bad behavior and good art.” Were you referring to Monsters?

CLAIRE DEDERER: In my previous book, Love and Trouble, I was talking about predatory men in the 1970s and ’80s and what it was like to grow up in that world, and the book contained two open letters to Roman Polanski. When I finished it, I’d done all this research on Polanski and knew all about his crime. And I was still able to watch [his] films. So I began to have the idea that this was a rich vein to mine, this question of How, if I know everything I know, am I still able to sit down and watch Rosemary’s Baby, etc.? I began noodling on that question in 2016, I think, and began writing what became Monsters. I was always intending to write a work of criticism [and] of personal exploration. So when #MeToo exploded in 2017, I already had the first chapter of the book written—the essay that was published in The Paris Review. I always conceived of that piece as an opening salvo. And then it went out into the world and was a standalone thing, which was a very strange experience, because I felt like, Well, I’ve only just begun! This is a throat-clearing! I have a lot more to say!

You’ve noted that of all the things you have written, that was the piece that men responded to, more so than anything you’d written before it. Were there any particular responses that still stand out to you?

CD: I’d been working on that piece for a year before it came out, but it looked [like] it was a hot take. It came out right in the midst of the [#MeToo dialogue], and it looked as if I was lobbing this little bomb into the conversation. The fact that people responded so strongly to it made me feel excited that there could be an exploration of this—or, in fact, of any subject—that could go beyond having a fight. I hadn’t realized how close the Woody [Allen] defenders were aligned with the men’s-rights movement. I’d written about Allen before, and I hadn’t really experienced their wrath, but this piece got so much attention—and I think also, I [got] caught up in a changing way that the internet is used, which is to name-search and attack. I got a lot of people who were creating accounts [just] to attack me about Woody. And that was really surprising, especially because I went out of my way to not talk about the Dylan situation; I was very specific in saying that this [piece] had to do with my response to [Allen’s] relationship with Soon-Yi, that my response was personal. And of course there were men who were like, Okay, here’s a feminist who says I can still consume these works, I’m going to align myself with her for cover, rather than engaging with what [I was] doing in the essay, which is trying to dismantle the idea of critical authority.

You write early in Monsters that you wanted to write an autobiography of the audience. And a running theme in the book is you checking yourself for using the collective “we” to describe the behaviors and expectations of audiences. It’s an interesting needle to try to thread: You’re a critic, but you’re also a fan. You’re a writer, but you’re also a consumer.

CD: What I was trying to look for were places where I was using “we” as a kind of escape route out of sloppy thinking. One of the ideas in the book is that when we’re consuming work, we’re having a subjective experience that has to do with our own historical identities. And so, in that way, the “I” voice became even more powerful, because I had to acknowledge who I was as a reader, as a consumer. I’m asking other readers and other critics to acknowledge their historicity, so I tried to bring that forward in my own analysis.

One of the things that’s happened with #MeToo and the other cultural reckonings of the past couple decades is a reconsideration of the belief that we should aim to separate the art from the artist. Do you think there’s still value in trying to separate them?

CD: Well, who’s the value for? Who is served by separating the art from the artist? I feel like the concern about that separation has [always] had to do with not interrupting the smooth flow from male artist to male audience, with male critic in between. If you say, “As a woman,” or “As a person of color” in responding, you disrupt what was formerly an unimpeachable—I use the word “alpine” in the essay, and I think in the book—and lofty exchange of ideas unmuddied by the mess of history. I feel like even in the time since I wrote the essay, and since I’ve been working on the book, the centrality of separating the art from the artist has started to seem kind of hoary and out of date.

It is still out there, though. And because it’s such a culturally enshrined thing, people who aren’t part of that white male creator-critic-consumer loop have certainly been told, overtly and otherwise, “You shouldn’t be feeling. You should be thinking.” Even when they themselves are feeling.

CD: Exactly! You’re feeling, for instance, comfortable. You’re feeling valorized in your point of view. You’re feeling untroubled. There’s all sorts of things you’re feeling! [Laughs.] I was just talking with another writer, and he was complaining about his experience of being perceived as a white male writer, and how much he hates for identity to define everything he does. And it’s like, That feeling you’re having is what everyone on Earth has had before you. This is the normal experience when [someone] is not you! They’re experiencing themselves as an identity, and they’re furious. So what do you do with that kind of grievance?

That really is the question. They can no longer pretend that the playing field is level, and are angry that other people made them see that.

CD: I think a lot about this text I got from a man, who I won’t name, about three years ago, talking about a female musician who was a pain in the ass. [His] text said “What do we do with the art of monstrous women?” As if he was catching me out. There was a really, really, really serious chapter in [Monsters] titled with [the question in] his text, in which I just had this enraged argument with him. Which I had to take out [laughs] because it was less writing and more just having a complete meltdown on the page. [That] refusal to see the power dynamic is something I encounter constantly. It’s a similar impulse that leads people to accuse [others] of “reverse racism.” I don’t want to co-opt that issue, but it’s the same kind of refusal to see that there’s an inherent power imbalance. If this person—the texter—acknowledges that there is a power imbalance that makes these two questions very different, what is he afraid will happen?

Monsters isn’t just about male artists, but it struck me that most of the men you write about are monsters because collective beliefs about what art is has let them be monsters. The women you write about are monsters because that same set of beliefs constrains them, and that’s a really major difference.

CD: Right. The beliefs about women are constraining, and the beliefs about men have to do with license.

I wish you had included that ranty chapter.

CD: I knew you were going to say that!

Well, if we’re going to talk about women as monsters, it should be about more than what they did in response to the forces keeping them from being artists. Obviously there are women artists who do terrible things, and that’s a fascinating subject in itself.

CD: Yes. And it’s something that people are starting to step into, in a very uncomfortable way. It’s a difficult dialogue, as you’ve seen from the way people have responded to Tàr. And it’s a problem of representation, right? I mean, the complaint is that if we’re going to have representation of one female [conductor] ever, then she has to be quote-unquote good. So it has to do with access, with telling more and more stories.

I think it also has to do with the idea of the male experience as the universal one. It’s historically less likely for men to consume stories about women artists, and if our stories are always about the one woman who did X or the first woman to do Y, you’re not going to be able to make one-to-one comparisons.

CD: Right. And that goes in a lot of other directions, where we can look at our own complicity as it relates to queer stories and stories from BIPOC people. How do I flip the paper over and look at what I’m doing, where I’m guilty of that same normalizing of my own experience?

That’s what makes this book so intense. There’s so much grappling. You’re not writing from an above-it-all vantage point. You’re in it. And it made me wonder about your writing process.

CD: My process. [Laughs.] The process was interesting. I’ve written a lot of criticism: I started out as a critic, I’ve written a lot of journalism, and I certainly know how to move through a series of ideas. But it’s very hard to write a book-length work of criticism. How do I both think my way through this problem, and also appear as a character in the book? What level of exposure do I have, of myself? How much do I appear? How much does a disembodied thinking voice appear? But I knew I wanted to tell Monsters as a story, so there was a lot of struggle with figuring [that] out. When you’re writing criticism, it’s floating free, it exists in this kind of atemporal space. But embedding that in story, it becomes complex. Wanting to show the story of my thought echoes the theme of the book, which is that our work [as artists] doesn’t just appear to us absent our historical experience, or our experience based on [our] identities. Struggling to put story around my thoughts is what I was doing on the page and what I was doing as a concept. One of the really hard things was realizing that my truest self is so ambivalent around these issues—that I really am divided, that I really do keep coming up against the ambiguity of the question [about the art of monstrous men]. The problem was getting through a draft and looking at it and knowing this is what I really thought, but [also] questioning myself. Like Am I trying to cover all my bases because I don’t want to get yelled at on Twitter? The only way I was going to be able to publish this [book] and be protected, psychically, was to know that I had [written] what was most true to me.

There’s an incredible interview with Melissa Febos where she talks about how you have to write for the good-faith reader. And I wish I’d read that at the time, but somehow I blundered my way to that [same] realization. I can’t surrender my own ambivalence because I’m afraid of overreacting to the bad-faith reader. I can’t not go in a [particular] direction because of the bad-faith reader. Once I thought that stuff through, it became much easier for me to poke and interrogate every sentence in the book and make sure I really believed it.

You use the term “art monster” in the book as a kind of shorthand for the person you have to be if you’re an artist and you’re going to get shit done. Is “art monster” an aspiration?

CD: What I’m getting at is that the self has to be held up, enshrined, and protected in order to make work. Talking about the art monster and the abandoning mother, along with the idea of “the shit in the shuttered chateau” who gets to be alone and make their work, is [talking about] the feeling that constrains me—the feeling that, when I shut the door and do the work, I am abandoning care. I’m trying to kind of scrape away the laughing ways we talk about this issue and say that underneath [is] the feeling that if I do my work I am letting down the people I care for. That really has to do with the essentialism that says [women] are the ones who can care. So much structure is built upon that idea. What if we start to take apart that idea and realize that care can be done by other people as well? Then does the would-be art monster start to get some relief from this problem of How do I make my work without feeling like a monster? And the idea that comes up vis-a-vis Doris Lessing and Joni Mitchell—and even Hemingway—is Will I ever make great enough work to justify the times I didn’t take care of people? There’s this idea that maybe you spend the rest of your life trying to make something good enough to justify the focus on the self. Which is a way to get things done. But I also know that taking care of people is what has kept me going in my darkest moments, and that I’m really lucky to get to do it. Which sounds really Pollyanna-ish, but it’s just a fact.

What do you hope that people take away from this book?

CD: Rather than an idea takeaway, I’d like people to have a kind of perspective or attitude takeaway, which is looking at one’s own assumptions about your relationship to this stuff and looking at your choices and your decisions as being a function of your own history, your own identity, your own subjectivity. That’s what I hope. And I feel like it’s happening. Although most people just want to know if they can still listen to Kanye. [Laughs.]

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.