Broken Medicine

Ectopic Pregnancies Are Not Viable Pregnancies. Period

It took centuries for medicine to recognize ectopic pregnancies. Now Ohio legislators want to force doctors to "reimplant" them in a woman's uterus—which is medically impossible.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

In cases of ectopic pregnancy, there is only one life to save: the pregnant person’s.

Yet ectopic pregnancy—when a fertilized egg implants outside of the uterus, usually in a fallopian tube—is the latest target in the fight against safe, legal abortion. An Ohio anti-abortion bill would see doctors required to attempt a nonexistent procedure to “reimplant” an ectopic pregnancy in the uterus or face charges of “abortion murder.”

But pregnancies outside the uterus are never viable. If left untreated, they can be life-threatening. These pregnancies may go away on their own after the body stops producing pregnancy hormones. But in many cases, the growing embryo will eventually rupture and cause internal bleeding. Burst ectopic pregnancies are responsible for somewhere between 4 and 10 percent of pregnancy-related deaths, and are the leading cause of maternal deaths in the first trimester. Thankfully, it’s an area of medicine where significant progress has been made.

“Until the 19th century the ectopic pregnancy was known as a universally fatal accident,” obstetrics professor Samuel Lurie noted in his 1992 paper on the condition’s history. “The main achievement in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy is the dramatic decrease in mortality rate: from 72 to 90 percent in 1880 to 0.14 percent in 1990.”

References to extrauterine pregnancy first appeared around 963 C.E. when Arab Muslim physician Al-Zahrawi, known as the father of modern surgery, described tending a patient with a swollen abdomen and small fetal remains emerging when the swelling was drained.

In the 1500s, a handful of procedures were recorded in Europe where a surgeon extracted an extrauterine fetus through an abdominal incision. It would be nearly 100 years before similar procedures were described. Unfortunately, as with many woman-centric ailments, a lot of patients died before medical men figured out what was actually going on. The word ectopic simply means “in an abnormal place.”

It wasn’t until the late 1600s that doctors began investigating the actual anatomical location of such pregnancies. After French surgeon Benoit Vassal performed an autopsy on a woman who had died from a burst ectopic pregnancy, he declared the embryo was growing in an “adjunct uterus.” (Despite fallopian tubes having recently been discovered and named.)

The woman had suffered for two and a half months before it burst, which “cast the mother into such violent convulsive motions for three days together, that she died of them,” Vassal wrote.

Peering through his rudimentary microscope, Dutch physician Reinier de Graaf did his best to scrutinize the reproductive tracts of rabbits and humans. Despite the instrument’s low power, what he observed led him to conclusions that challenged many long-held assumptions about reproductive anatomy. One being that the purpose of fallopian tubes was to deliver air to a developing fetus.

In a letter to the Royal Society of London, de Graaf declared eggs use the tubes to pass from the ovary to the uterus, and ectopic pregnancy occurred when a fertilized egg got caught in transit: “As such a fetus grows it prepares death for its mother,” de Graaf warned. He concluded that Vassal had mistaken the tubes for a “second womb.”

De Graaf was also the first to notice that damaged tubes were more likely to house an ectopic pregnancy. The risk of ectopic pregnancy is now known to be higher if you have pelvic inflammatory disease or endometriosis, use tobacco, have an IUD, or undergo fertility treatment.

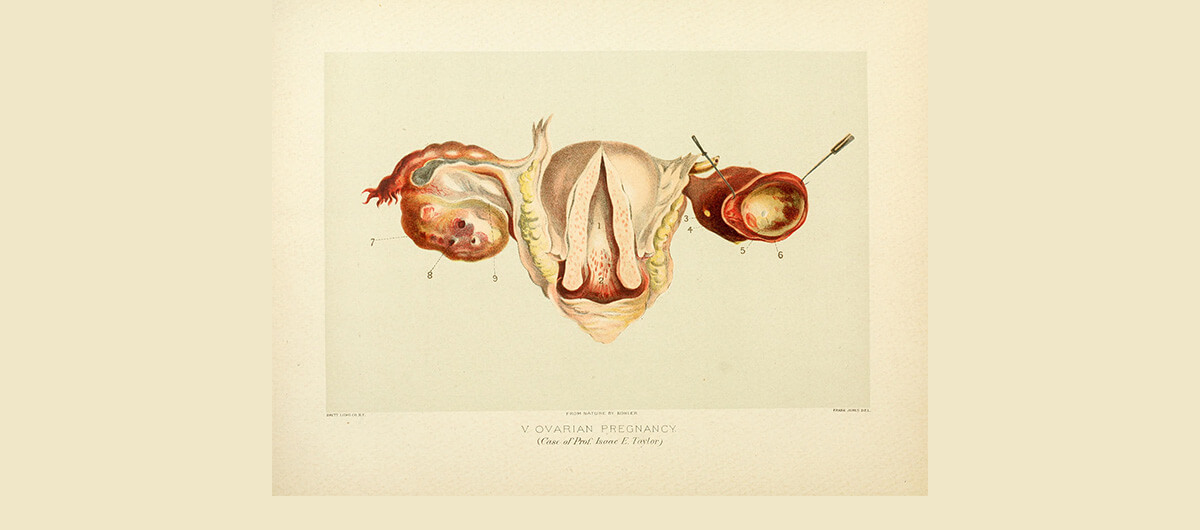

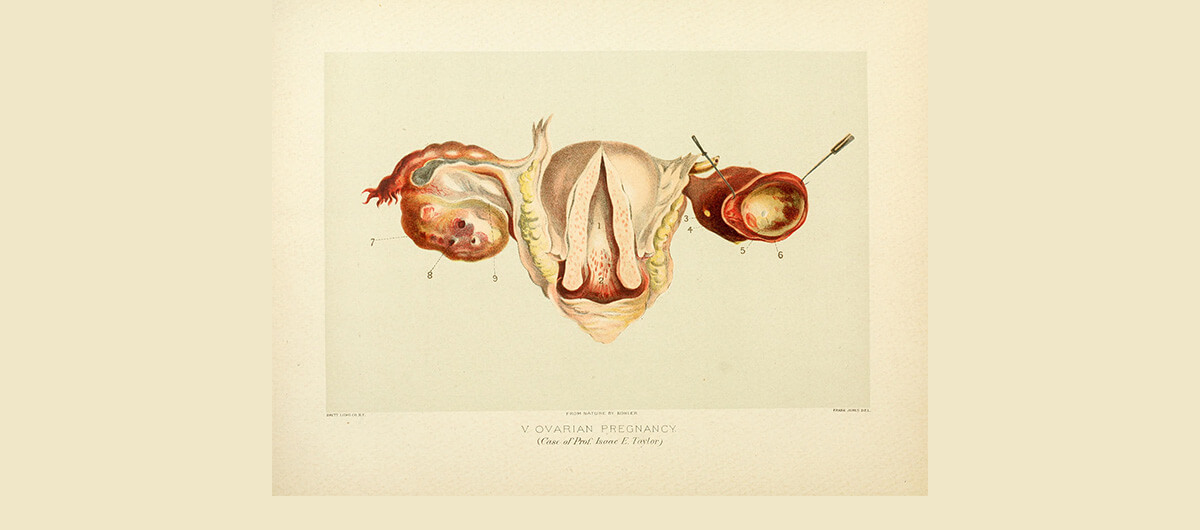

It’s important to note that at the time, the term “ovary” was not yet widely used. Women were considered underdeveloped versions of men. Ovaries were referred to as testicles. Most ectopic pregnancies happen in fallopian tubes, but they can also inhabit ovaries, c-section scars, and the cervix.

In 1683, the first case of an ovarian pregnancy was described in the French Journal de Medicine. Just before her death, the woman “complained of a great colick in the region of the right groin,” her physician reported. “This colick was so violent that as I was going to touch the place, she prayed me not to press it, and told me I would make her fall into a swoon.” Upon examining her body post-mortem, the doctor found the woman’s “testicle” (ovary) had been “torn longways and through the middle.” Inside, he found a fetus about the size of a thumb. Pain and bleeding only occur in about half of ectopic pregnancy cases. The rest of the time, there may be no symptoms at all prior to rupture.

Most treatments focused on attempting to destroy the fetus before it killed the mother. Doctors’ therapeutic arsenal included strychnine, starving, purging, and blood-letting of the mother, and morphine injections and electromagnetic currents applied to the ectopic mass. But whatever the treatment, the prognosis was grim.

Of the next wave of operative interventions, the first two procedures proved successful (meaning the pregnant person survived): one in 1759 in New York and one in 1791 in Virginia. Of the 30 operations that followed, five women lived.

By the time they sought medical attention, many of these women may have already been in shock or near the point of rupture. Anaesthesia and germ theory were still a long way off. If you weren’t already in shock, being awake during surgery might take care of that. A surgeon’s tools and clothing were rarely cleaned between procedures. Those who underwent surgery were often more likely to die than those treated with other methods.

Things started getting better in the late 1800s. In the U.K., Robert Lawson Tait was hard at work investigating the anatomy of women who’d died of a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. A trailblazing surgeon, he’d recently performed the first ovariotomy and the first appendectomy. And he dared to wash his hands, boil his instruments, and launder his linens prior to operating.

Before long, Tait developed a new and improved surgical procedure. It involved tying off the broad ligament of the uterus, removing the affected section of fallopian tube, and suturing any bleeding vessels. Thus the “salpingectomy,” or surgical removal of fallopian tube, was born. After Tait’s first successful salpingectomy in 1884, it became the go-to ectopic pregnancy treatment worldwide for the next 70 years.

It was the development of anaesthesia that made surgeons like Tait more daring in their abdominal operations, and some feared, too overzealous. Doctors didn’t always agree on whether to err on the side of caution by operating at the first sign of a suspected case of ectopic pregnancy, or to wait things out. Many times, surgeons found no misplaced embryo, but instead uncovered the true cause of the symptoms, such as ovarian cysts.

Even into the 1950s, a preoperative diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy was found to be wrong in about 20 percent of cases. Conversely, of all the ectopic pregnancies discovered during surgery, 20 percent had been diagnosed as something else. A few doctors thought operating immediately after an ectopic rupture was also ill-advised: too little, too late. One Dutch physician favored ice packs and opium, believing it might stem internal bleeding.

Belief that an ectopic pregnancy wasn’t always the result of a diseased fallopian tube, combined with the realization that women wanted to preserve their future fertility led to more conservative treatment options. Still, accurate diagnosis of an unruptured ectopic pregnancy remained elusive. When ultrasonography was finally widely employed for gynecological use in the 1960s, diagnostic accuracy shot up to 40 percent.

Throughout the 1900s, thanks to the introduction of aseptic surgery, antibiotics, blood transfusions, and improved pregnancy hormone tests, the mortality rate from ectopic pregnancy dropped precipitously. Between 1908 and 1920, it was 12 percent, but from 1937 to 1947 it was down to 2 percent. Between 1980 and 2007, only 876 people died as a result of ectopic pregnancy in the U.S.

Today, if discovered early, most cases can be treated with a low-dose injection of methotrexate, which acts to stop rapidly dividing cells. And 85 percent of women who’ve experienced an ectopic pregnancy go on to achieve a uterine pregnancy within two years. To willfully assert that ectopic pregnancies are viable is to eschew centuries of treatment improvement, and likely return to near-universal fatality.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.