Racism

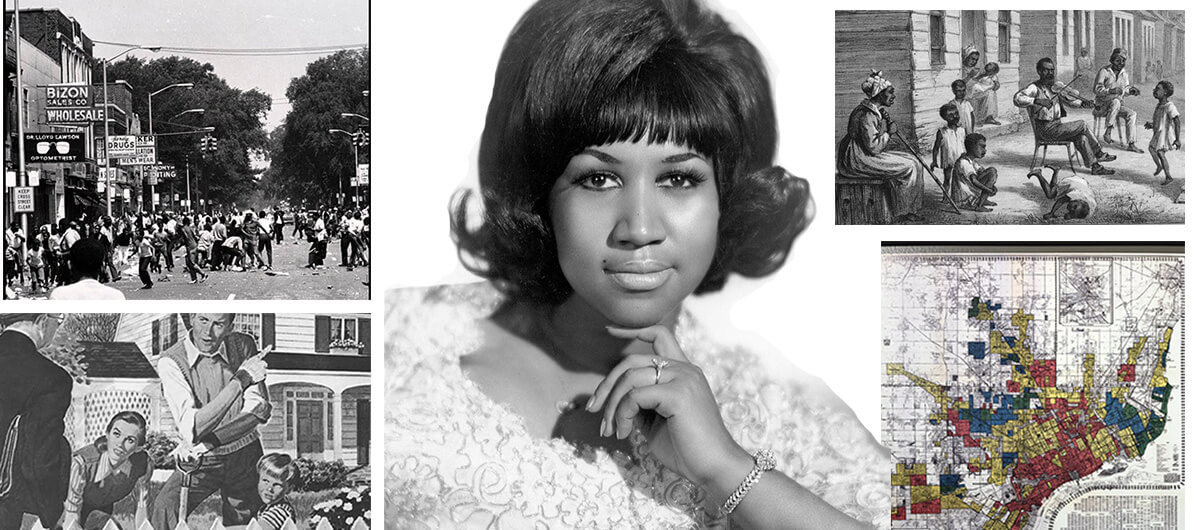

What Aretha Franklin Taught Me About White Flight

A white Jewish writer reflects on his family's role in segregation politics, and how the Queen of Soul and other Black artists connect him to this history.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Before I knew anything about slave songs, their nature or traditions, I relied on Aretha Franklin’s version of the popular spiritual, “Mary Don’t You Weep” from her live album, Amazing Grace, as a ballast in moods of frustration. I’ve been thinking about it a lot since watching the long-delayed, finally released Sydney Pollack concert documentary, Amazing Grace—about Franklin’s legendary performance—which was released worldwide this past April, and which will be coming to DVD in August. The more I investigated the song, the more I felt it is too easy for a white audience to consume powerful Black art as a salve, when it is actually a prophetic call for repentance. At first, I felt this disconnect in a vague, impersonal sense. As a white writer living in Harlem, aghast at the cruelty of white supremacy in our country, I felt a dissonance in casually consuming Black Art. When Aretha soothed her people with the chorus of the spiritual, “Mary don’t you weep, don’t your mourn, Pharaoh’s Army they got drownded in the Red Sea,” wasn’t that blasphemous, I asked myself, to use that solace for my mundane middle-class life, while Pharaoh’s Army continues to gun down Black people in the streets, on their front and back lawns?

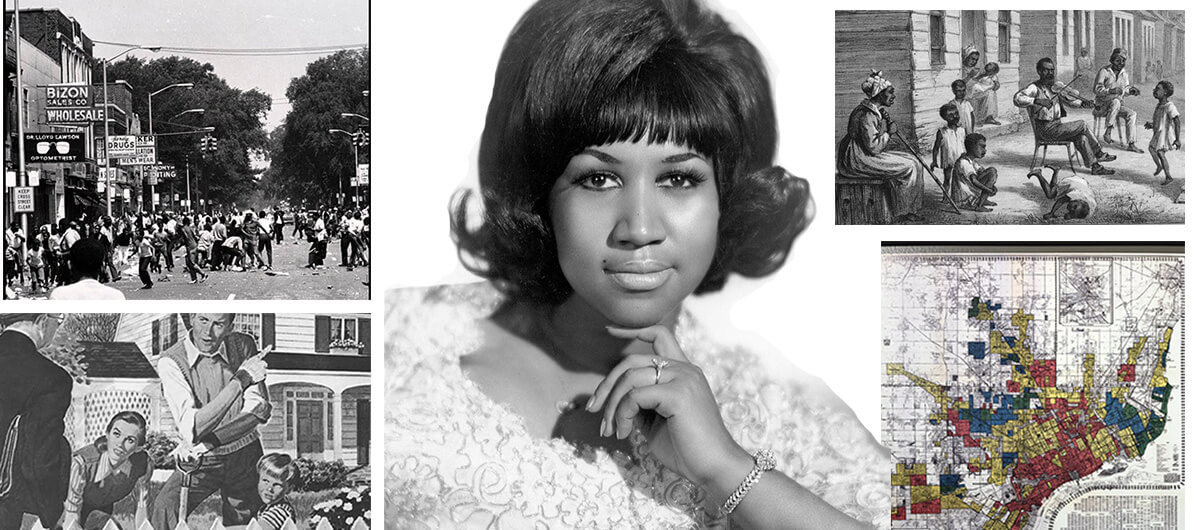

This sense of unease led me to research Aretha’s life in Detroit, along with the history of slave songs. What I learned turned this vague sense of dissonance into a personal indictment of my American Jewish experience. Looking into the unspoken history of my family in Detroit, I understood that when Aretha was urging her people to hope with the watery death of Pharaoh’s Army, my family was included in that call for vengeance. My people were part of Pharaoh’s Army to the Black Detroit community. We were, along with other white immigrant groups, the perpetrators and beneficiaries of a White Flight that sucked Detroit dry. How then do we relate to art that implicates us? What responsibility does it engender in the listener or viewer, I kept asking myself.

Aretha was only 30 when she performed the now-historic two-night concert for a packed house at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Watts, Los Angeles. The album, Amazing Grace, would be released in June of 1972. It was only seven years earlier that a Black uprising in Watts rocked the neighborhood. Watts was still reeling, and gang violence was on the horizon. The neighborhood, like too many American cities, was home to Black migrants from the South looking for a better life, only to be divested by White Flight and oppressed by an all-white police force.

Aretha would win a Grammy for her performance of the hymn “Amazing Grace,” a song written by a white slave trader, and the album would go on to be the best-selling of her illustrious career. It currently reigns as the best-selling gospel album of all time. With her recent passing, many used the album to highlight how Aretha’s career and trajectory was grounded in her gospel roots. The record (and the long-delayed, finally-released Sydney Pollack documentary of the famous concert) opens with the slave song, “Mary Don’t You Weep.” Over a rhythmic organ the Southern California Community Choir under the direction of Reverend Dr. James Cleveland, chants, “Oh, oh Mary,” over and over again. The organ and bass start up and almost a minute later we finally hear Aretha, “Mary … don’t mourn,” she croons over the organ and the choir. “Listen Mary, tell your sister don’t mourn. Pharaoh’s Army, all them men got drownded in the Red Sea.”

On this song, she sings like her father, himself a reverend in the Revivalist style, with a colloquial twang in a rousing voice. Her voice is young but assured, gentle yet commanding as she consoles the crowd with a reminder of the slave master’s death, of the downfall of evil empires, of unexpected resurrection. By the fourth minute she’s shouting with joy over the waltzing claps of the audience. By the end, seven minutes in, her mezzo-soprano is no longer in the realm of joyous consolation, but has taken the crowd to a soaring feeling of redemption, of a communal resurrection as miraculous as Lazarus.

In fact, Aretha’s version of “Mary,” as explained in one of her father’s more famous sermons, was a direct indictment of this White Flight. Before he was known as the father of the one and only Queen of Soul, Reverend Clarence LaVaugh Franklin was one of America’s most famous pastors and civil-rights activists. His rousing sermons on topics of hope, justice, and salvation were heard by millions around the globe. Growing up, Aretha often followed him around on tour. He fought for the Black United Auto Workers in Detroit, and was one of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s strongest supporters, even when others in the community thought MLK too radical. His home in Detroit was like a saloon for artists, musicians, preachers, and activists all of Aretha’s life. One of his more popular sermons, “Without A Song” was on the topic of singing in a foreign land, of the Black experience in America, and of the power of song in the Black community. He specifically references one of these examples of Black Americans singing in the face of oppression in the slave song, “Mary Don’t You Weep.”

He begins by recounting the story of the biblical Israelites in Babylonian exile. Their Temple was destroyed. They were taken as slaves from their homeland, and thereby the rivers of Babylon, the Book of Psalms records, their captors asked the exiles to sing. The slaves replied, “How can we sing God’s music on foreign shores?” Here Reverend Franklin argues, “The Israelites should have sung!” For Franklin, singing in the face of the oppressors has been the unique spiritual heritage of African Americans. They sang where the Israelites would not. To sing in the face of the oppressor is not an act of cowardice, of pleasing the master, but of spiritual strength.

He then builds his case, using historical precedence of singing with and to the oppressor. Traditionally, the Mary of the song has always been Mary, the sister of Lazarus in the New Testament, crying over her dead brother, but Franklin offers a more contemporary explanation of Mary’s identity. Mary, he explains, was a Southern slave who wanted to hear a white preacher preach in a white Church, but her masters would not let her listen. They could not accept praying with their slaves. Rejected, a fellow slave consoled her and urged Mary not to stop praying, not to stop singing God’s songs, because eventually Pharaoh’s army was drowned, eventually the Israelites had their prayers answered. So too will all these modern-day Pharaoh’s armies, all these white masters and enablers, get drowned in the Red Sea. The slave song, the music of black communities, Franklin opines, is hope in the form of Divine vengeance.

With this example in mind, he brings the sermon to a conclusion with a contemporary focus. Whereas Black people in America have had the spiritual strength to sing their oppression to their oppressors, white people have fled from Black people because they are afraid to listen. Referring to all the white people who fled Detroit for the safer white-only suburbs, he diagnoses their problem as religious: “When you got too much religion that you can’t mingle with people, that you’re afraid of certain people, let me tell you got too much religion …”

Essentially, he compares White Flight to the slave masters inability to pray with their slaves. In both cases, he argues, White people were too cowardly to properly hear the song of the oppressed. Instead of listening to these songs of sorrow and freedom, they segregated themselves so as to not have to see the true consequences of their sins. It is a shocking comparison, especially as I came to realize Franklin was not talking to me in any abstract way as a white American, but directly to my great-grandfather, among other white immigrants who fled to the suburbs of Detroit.

My great-grandfather, Rabbi Yosef Ben-Zion Rabinowitz, was the scion of the Brezener Hasidic dynasty. He was desperate to leave post-revolutionary Russia. On a trip to America in 1929, his prayer was answered in the form of the American Brezener Hasidim living in Detroit. The small group implored him to stay in America. He needed little pushing, and although the immigration gates were closed in the cruel and racist Immigration Act of 1924, the status and strength of the Jewish community allowed him safe passage into America. He first lived in a modest apartment on 12th Street, above his small synagogue, only a few blocks away from Reverend Franklin’s Church, New Bethel Baptist. Just a few years later, Rabbi Rabinowitz followed his community toward the suburbs and found a new two-family home on Blaine Street. The community helped him buy the house at a low price from the bank, during the Depression. It needs to be said that there would have been no way for a Black person at the time to get a loan from the bank, let alone buy a house from the bank at a cheap price. At this time, Realtors were gouging prices and rents for Black people, when they were letting them buy houses at all. Locals gathered into community groups to intimidate and threaten Black families trying to move in. A few years later Rabbi Rabinowitz was able to buy a posh, seven-room home on Dexter Street, on the border of the suburbs. The new shul was built in the Modernist style, and its opening was covered in the paper. My family had arrived. This lowly rabbi from Russia now had a fancy home with a master bedroom, and a backyard, surrounded by people who were white like him.

As our family established themselves firmly as middle class, as my great-grandfather successfully fulfilled the American dream, all the while Detroit seethed from decades of an all-white police force, of hiked-up rents and negligent landlords, of divestment and redlining, of racist banks and violent white people who simply could not imagine themselves living next to Black people. Eventually, after moving twice to “better neighborhoods,” as my family would say, my great-grandfather, born in the land of the Russian Empire, who was saved by the American one, took final refuge in Israel, a young budding Empire, still unfinished in its business of colonization. The transformation from Israelite to Egyptian was complete. He left his home in Detroit to move to Jerusalem about six weeks before the summer riot of 1967, as the white community came to call it.

The Black community knows it as the Detroit Uprising. These different viewpoints sound like the difference between an Israelite and Egyptian viewpoint, but I’m certain my family doesn’t see it this way, or even think about it. But this is the untold story of my community of white immigrants. We don’t talk about it. We don’t reflect on the moral obligations created by our embrace of White Flight, how we benefited from it, how we made money, bought houses, and established ourselves as stable in our middle-class status. To save ourselves, we bought into oppressing others.

It doesn’t help to know my great-grandfather wasn’t alone in his cowardice. Describing the contrasting experiences, the historian Dominic J. Capeci Jr. writes that during these 30 years of prolonged White Flight, “Most Blacks endured an American nightmare; many Jews experienced the American Dream.”

In the same vein, in her book, Metropolitan Jews: Politics, Race and Religion in Postwar Detroit, the historian Lila Corwin Berman writes that “As urban dwellers,” Berman continues, “Jews often championed the ideals of integration while personally benefiting from a racist housing system that exploited Black Americans’ desperation for and exclusion from decent housing and mortgages. And when Jews left cities in the second half of the 20th century, they materially disinvested in urban life in the same way as countless white Americans.”

Returning to Aretha’s version of Mary, knowing what I now know, it is impossible to respond to it as I once did, in my naïveté. The song is a gift, but not in the simple form of spiritual uplift. Instead, the song accuses and interrogates. Now when I listen to it, I feel called before the court of Justice. Surely this ought to be true of Black art for white people in the American cultural landscape; it’s often asking an accusatory question about unfulfilled justice. However, like the masters before us, we’ve adapted new ways not to listen, though we might champion Black art and artists. We listen, but we do not act. We listen, but do not sacrifice. The best and most assured way not to listen is to indulge in the mundane white American ignorance of history and nature of Black culture, is to not see the prophetic in Black art.

It became apparent how ignorant I was and continue to be as a white consumer of Black art. I was taking spiritual sustenance from a song that was a direct indictment of my American life. To casually consume Black art is to miss the raging prophecy at its heart. Prophecy is nothing less than a constant reminder of our sin. Slave songs, I learned, beautiful, elegiac, were a central component of slave religion. Without permission to pray in the white church, enslaved people took to the forest and sang these songs of hope and justice. These songs were always subversions of the white order in which they were able to honestly depict their masters as Pharaoh’s army and themselves as the true Israelites. The songs were also used in acts of rebellion, written up in righteous books of condemnation, as proof of Black spiritual genius.

In 1849, at age 29, Harriet Tubman steeled herself to run away from her master’s house in Maryland. But how do you tell people the news, she asked herself that fateful day, how do you properly say goodbye to your friends and family without giving away your plan? Runaways were hunted down and captured. They were often severely punished. Some owners branded runaways with an R on their cheek. Knowing she needed subtlety, we are told in Sarah Bradford’s Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, Tubman sang about her freedom. She chanted a hopeful slave song:

I’ll meet you in the mornin’

Safe in de promised land

On the oder side of Jordan

Boun’ for the promised land.

All the Black people, all her family and friends, understood what she was singing about. Only a year later, in her freedom, Tubman used the songs to guide slaves through the Underground Railroad, to tell them whether it was safe to hide or emerge from the forest.

Four years earlier, in 1845, newly freed slave Frederick Douglass used the slave songs as part of his righteous polemical purpose. “I have often been utterly astonished,” he writes early in his second chapter of his Narrative of a Slave Life, “since I came to the North, to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness.” Rather, the songs, he writes, “told a tale which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones, loud, long and deep, breathing the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains… Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds.”

After the Civil War, the songs took on widespread popularity because of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. In 1871, facing dire financial issues, Fisk University sent out nine students as an a capella group singing spirituals to raise funds. Despite the endless racism they experienced, they became a beloved act that performed in front of the American president and European royalty. They made $150,000 and with those funds, the historic university was able to build its first permanent building, the Jubilee Building. Ella Sheppard, one of the original nine choir members, who composed and arranged the music while singing, playing the piano, the organ, and the guitar, explained the spiritual dynamics of popularizing slave songs:

“They were sacred to our parents, who used them in their religious worship and shouted over them… It was only after many months that gradually our hearts were opened to the influence of these friends and we began to appreciate the wonderful beauty and power of our songs.”

In Sheppard’s telling, they are a sacred gift that is shared with white people but surely that act of sharing a sacred slave song about white oppression requires something from its white listeners. A few decades later, W.E.B. Du Bois, would add to this idea, explicating the nature of the gift in what he called the Sorrow Songs. In 1903, in the 14th chapter of the book The Souls of Black Folks, Du Bois described the history and power of the sorrow songs, echoing what Douglass said, but, given that it was already almost 50 years since the end of the Civil War, Du Bois added a new layer to the sorrow songs that had accumulated in the preceding decades. Speaking of the sorrow songs as a body of work he wrote that, “it has been neglected, it has been, and is, half despised, and above all it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.”

Slave songs, he contends, are a gift to white people, to the oppressor, but what is the gift here? “Through all the sorrow of the Sorrow Songs there breathes a hope,” Du Bois writes “a faith in the ultimate justice of things. Is such a hope justified? Do the Sorrow Songs sing true? Generation after generation we have pleaded with a headstrong, careless people to despise not Justice, Mercy, and Truth, lest the nation be smitten with a curse…”

They are, I believe he is explaining, the gift of prophecy and of moral clarity. They are accusations and reminders of broken promises and empty values of White America. This is the gift of a song like Mary Don’t You Weep. For what white person can say they are not a part of the Pharaoh’s large army?

I’m reminded of a speech James Baldwin gave at Berkeley College in 1979. He was discussing the strangeness of being born into a language that is antagonistic toward the Black person. He notes how white people sanitize the language to erase Black people’s experience. The term ‘Civil Rights movement’ is an American creation to sterilize the true intent of what had happened, he argues. “Instead, he says, “of speaking about a Civil Rights movement, which is an American phrase, which upon examination means nothing at all, let us pretend, that I stand before you, as a witness to and a survivor of the latest slave rebellion.”

If American history is truly the history of an unfinished slave rebellion, then Pharaoh’s Army still exists and thrives. From that measurement, it’s hard to see what, short of actual rebellion and revolution, would be enough as a reply to Black art. In a time when we want our art to be just, to do the work of social justice, to change the world and create political waves, I think we artists, especially white ones, need to wonder if our art is the answer to these accusations, to these reminders of justice deferred and wished-for vengeance. Is writing enough to answer the charge of these sorrows songs, or are we simply evading the radical responsibilities these prophecies engender? More and more I remind myself that for white people in America, Black art is too often used as balm, when we should utilize it as a thorn, as constant, painful reminder of our broken promises and of cosmic justice, deferred.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.