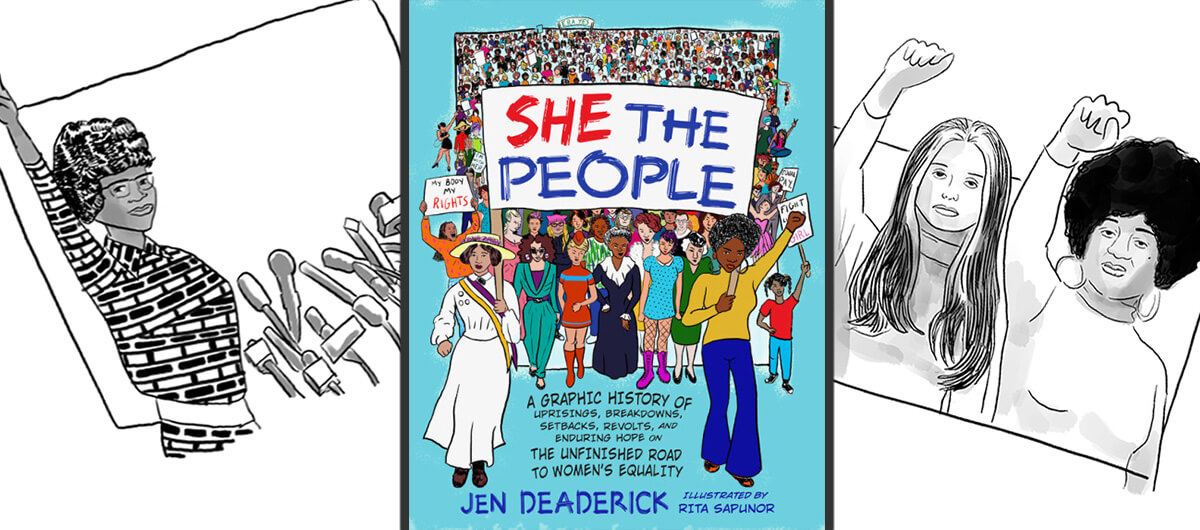

Illustrations by Rita Sapunor

Women's History Month

Illustrations by Rita Sapunor

The Feminist Roar Heard ‘Round the World

From Rep. Shirley Chisolm's bid for the presidency to the passage of Roe v. Wade, here is a primer on one of the most exciting eras of feminist rebellion in this exclusive excerpt from SHE THE PEOPLE, a graphic history of our path to equality.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

There’s really only one thing you need to know to understand how cool and mainstream feminism was in the early 1970s.

On January 18, 1973, the Dingaling Sisters, an in-house singing group on the Dean Martin Show—yes, that Dean Martin—appeared wearing amazing shimmery bell-bottomed pantsuits with enormous feathery pom-poms on the sleeves and sang the feminist call to arms, “I Am Woman.”

This was not a gag, either. They were serious, despite their required showgirl smiles. They commanded the stage, charging forward, stepping with conviction, strong and invincible. The soloist in the number was Jayne Kennedy, who went on to an incredible, groundbreaking career, and the camera moved in for close-ups when she talked about wisdom born of pain. Her hair was at least styled to look natural, done up in an afro with a braid headband and maybe just a little bit of straightening on the front. This, of course, was a big deal. Kennedy was an African-American woman presented as desirable and glamorous on a television program hosted by one of the Rat Pack, and her hair wasn’t straightened. The early ’70s were magical.

The video clip ends with each sister—Kennedy, Helen Funai, Michelle Dellafave, and Lindsay Bloom—getting a turn at a close-up, staring defiantly and proudly into the camera as she sang the words “I am woman” over and over. When you learn that this act was sandwiched between Dean and Steve Lawrence doing a bigamy sketch and a rousing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” medley with the whole cast and the two guest stars, it makes the whole thing even more amazing. The hope and confidence in the future that comes through is so intoxicating that it’s easy to forget what happens later. But we’ll get to that.

Right now we need to celebrate the remarkable feminist cultural explosion of the early 1970s.

Yes, behind-the-scenes legal work was still happening. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, already considered one of the finest legal minds in the country, founded the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and started knocking down gender discrimination right and left with a fervor that would make her notorious.

No-fault divorce was legalized, meaning no evidence of an affair or other misdeeds was needed to end a marriage; the two people in the marriage simply had to mutually agree to end it. Divorce rates shot up. This was, of course, a mixed bag, as any kid who grew up in the seventies could tell you. The social and legal systems weren’t yet set up to handle the repercussions, and things got sort of chaotic. As is still the case, divorce could be devastating financially for a woman, particularly if she was left to raise the kids on her own.

Still, it was empowering for a lot of women just to know that they were able to walk away from the domestic sphere. There was a moment of reckoning in a lot of marriages. Some survived, some didn’t.

When Mary Tyler Moore decided to produce a show in which she would star as a single woman, it had to be made clear in the first episode that her character had broken off an engagement with a schmucky doctor, and was not divorced from the beloved Dick Van Dyke. Specifically centered on a single woman, Mary Richards, whose primary focus was a career that she loved, the show was aimed at women around the country who were trying on this new possibility. The title sequence started with clips of the character anxiously but determinedly driving into her new life, with the classic theme song echoing the concerns of so many women in 1970s: How will you make it on your own? This world is awfully big, and girl, this time you’re all alone.

It concluded with the reassuring “You’re gonna make it after all,” sung twice for emphasis. Then we fade in to Mary Richards’s world, with its close-knit workplace, gruff but encouraging boss, and cool apartment with a best friend upstairs. The job, working for a TV news show, is interesting and challenging and allows her to develop her skills and advance up the ladder. Over the course of seven seasons, we watch her grow from a nervous young woman into a competent professional, and though she dates a lot of men over the years, and ends up in a happy romantic partnership with someone who treats her as an equal, she never marries, by choice.

The show was an idealized portrayal of a single woman’s working life, but no more idealized than most television shows about men’s working lives. Moore had, after all, starred on The Dick Van Dyke Show, which portrayed a work life even more fun than the newsroom at WJM. Like her previous show, The Mary Tyler Moore Show also explored issues of the day like equal pay, white male privilege—few have ever been a greater example of White male privilege than Ted Baxter—and the day-to-day realities of being a woman in the world. But funny. Really funny. Women whose single lives were less ideal appreciated the chance to visit with Mary Richards once a week.

In an early episode, Mary’s scrappy best friend Rhoda is shown reading a copy of Ms. magazine. Founded in 1971 by Gloria Steinem, the best-known feminist leader of the time, and Dorothy Pitman Hughes, an organizer and activist in New York’s Black community, the magazine was conceived as an alternative to the women’s magazines of the time that were owned and controlled by men, which devoted a lot of pages to fashion and housekeeping. Ms. focused on politics and social issues filtered through a feminist lens and devoted space to stories that were considered tangential by the male editors and publishers of other news magazines.

For years, the magazine’s most difficult task was finding advertisers that weren’t the traditional women’s magazine advertisers, like makeup lines and fashion producers, who often expected strict control over editorial content and were economically dependent on shaming women about how they looked.

Other companies resisted marketing to women, thinking it would dilute the seriousness of their brand, or simply refused to see themselves as producing products for women. Steinem has often told of approaching auto companies armed with statistics about the growing number of women buying cars on their own to ask them to produce ads for the magazine. Over and over, male auto executives responded, “Women don’t buy cars.” Even with the numbers laid out in front of them.

Shirley Chisholm saw future possibilities more clearly. A skinny Black woman in glasses, she had a powerful charism and brilliant brain that overpowered anyone who underestimated her. In 1968, using the slogan “Unbought and Unbossed,” she was the first Black woman elected to Congress. In 1972, she decided to run for president. As she put it, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.” Although she was serious, and truly would have been a hell of a president, few others took her seriously. Prominent white feminists backed her at first, but not seeing a possibility of her winning even the nomination, they hedged their bets by also backing more conventional candidates. At the convention, though, to honor her bravery and accomplishment, several of the candidates who also had no chance of winning the nomination threw their delegates to her. It didn’t put her over the top, but it showed her the respect she had earned.

Also looking to the future, Marlo Thomas, former star of the very first TV show to portray a happily single woman, That Girl, produced a feminist kids album Free to Be…You and Me in 1971. The gentlest possible feminist propaganda, the album pulled in some of the country’s most popular entertainers to talk about gender roles, sharing work, and feelings. Rosey Grier, the football player, encourages boys to cry in one of the most touching songs ever recorded. Alan Alda joins Marlo Thomas to tell stories of a boy who wants a doll and a princess who doesn’t want to marry right away. Dick Cavett reads a poem about trying to determine his dog’s gender based on plumbing skills, Diana Ross sings about the oppressive exceptions of gender roles, and Carol Channing lets kids know “Your mommy hates housework, your daddy hates housework, and I hate housework, too. And when you grow up, so will you.”

The album sold half a million copies in its first year, and the project was expanded into a TV special two years later, with the same songs and poems and stories plus added content. Copies of the show were made available to school systems, meaning that every single child in certain liberal enclaves grew up knowing about William, the boy who wanted a doll.

As women continued to roar—in numbers too big to ignore—two major political shifts occurred.

The first came from the Supreme Court. Whereas birth control had been fully legal for almost a decade, termination of a pregnancy was still illegal in most states, meaning women were still having to go underground if they wanted an abortion. Performed outside of hospitals, and usually with limited medical standards and no aftercare, illegal abortions were dangerous and often deadly. In Chicago, the women-run Jane Collective organized to perform safe underground abortions, but it always ran the risk of arrest, as did the women terminating their pregnancies.

At the same time, in states where abortion was legal, women could openly access safe abortion services performed by doctors and receive professional care afterward.

Seeing the radical difference that this open access made in women’s lives, activists began to push for full legalization. State- based activism sought to turn over the laws on the books but also court cases were pursued in the hopes of taking the issue to the Supreme Court.

Finally, in 1973, Roe v. Wade, a case in which a young woman was suing the state of Texas for access to an abortion, was heard by the justices. Citing privacy rights, the court ruled that the government should not have jurisdiction over a woman’s health decisions, and, therefore, states could not prevent access to abortion in the first and second trimesters. The third trimester, when a woman carries a more fully developed fetus, was considered a grayer area, and the justices left it open to the states about how to regulate that stage, when pregnancies are rarely terminated, and then only when a woman’s life or health is in danger or in other extreme circumstances.

Beyond the specific expansion of reproductive access that came out of the ruling, it also made a statement about who should be in charge of a woman’s body, making it plain that it should be the woman herself. It would seem to go without saying, but the highest court in the land still needed to decree this.

A year earlier, the legislative and executive branches of the federal government had made a similarly profound statement: 50 years after first being introduced in Congress, the Equal Rights Amendment passed the House and Senate! By huge margins! Then it was signed by President Nixon, who was clinging to office by his fingernails.

Altered slightly from Alice Paul’s original version, it now read simply, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

The coolest part: Alice Paul was still alive and got to witness her amazing accomplishment.

The amendment was then sent for ratification to the states, which competed to be the first to ratify. Hawaii won the honor. The amendment needed approval by 38 states to be fully ratified. The House had passed a bill giving the amendment of seven years to get all the necessary state ratifications. But whatever. How could it be a problem? Look at how excited everyone was! I mean, the Dingaling Sisters had sung “I Am Woman” on the Dean Martin Show! We were golden, right?

As we know by now, it’s never that easy.

Adapted from She the People, written by Jen Deaderick and illustrated by Rita Sapunor, with permission from Seal Press, an imprint within Hachette Book Group. Copyright © Jen Deaderick, 2019.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.