#MeToo

How Do You Teach a Bad Man’s Good Art?

In the wake of #MeToo, professors grapple with how to teach culturally important art while reckoning with the abusive, misogynist nature of some of its creators.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

This spring, Michelle Rodino-Colocino was faced with a conundrum.

The Penn State professor was looking for a film with which to counterbalance D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, the white-supremacist propaganda film from 1915, for her entry-level communications course, Media & Society. Wouldn’t 2016’s The Birth of a Nation, made by Nate Parker and Jean McGianni Celestin, be perfect? Except … wasn’t there something controversial about that film, too? Oh, right.

“There’s no way that I could do this,” Rodino-Colocino says of showing the 2016 film, given that there were infamous rape accusations against its filmmakers, and especially because the incident allegedly happened while they were enrolled at her university, where students routinely come to Rodino-Colocino to share their experiences of sexual harassment and assault. She instead showed footage from James and Floyce Gist’s 1930 Hellbound Train, together with excerpts from Mark Cousins’s 2011 television documentary, The Story of Film: An Odyssey.

“I don’t need to show Birth of a Nation,” Rodino-Colocino says. “I can get at it with these voices that have been marginalized in our history books.”

Since movements like #MeToo hit a fever pitch last fall, there has been plenty of conversation around what we should do with the art of bad men or the stone-cold reality that most of us will continue to, say, listen to their music even as campaigns like #MuteRKelly gain prominence. And from a personal standpoint, making an informed decision about which art you choose to acknowledge or enjoy makes sense. In academia, where educators both have the responsibility to discuss art in a historical context and are confined to the harsh reality that much of said art that has survived through the years is made or derived by men—some of whom led atrocious, or at least questionable, personal lives—things get dicier. How do you teach the future in a film history class when the very industry you’re studying has a long reputation of suppressing voices that speak out against the status quo?

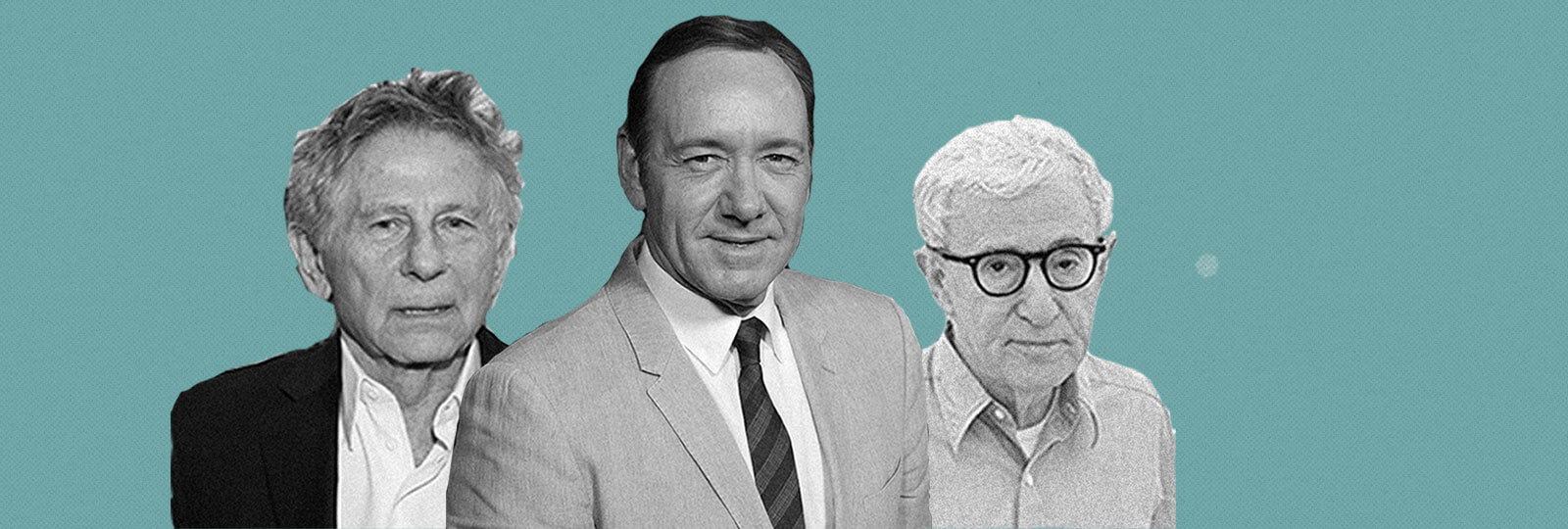

Now professors find themselves quite publically walking the line of acknowledging the impact that artists like Roman Polanski or Woody Allen have had on the pop cultural canon while also struggling to include examples of similar works made by people with less troubled pasts.

Some changes have been subtle but significant. Among other alterations to his lesson plans, University of Florida’s Andrew Selepak replaced an image of Kevin Spacey in House of Cards with Matthew Broderick in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off when he simply needed an example of a character breaking the fourth wall—he didn’t need one that also featured an actor who’d been accused of assaulting young boys.

Other changes have been about listening to the students who are either triggered by documentation of past injustices or feel concerned with how to interpret the work through today’s theoretically more enlightened society. And professors are forced to explain that deleting these horrible things from the conversation doesn’t mean they will disappear from cultural history (or, more importantly, won’t come back).

Michael Budds, a music professor at the University of Missouri who once lectured me on the importance of understanding that people like Chuck Berry could be both horrendous humans and influential artists, is still figuring out this push-pull with a new generation. (In addition to his legendary temper, Berry served federal prison time for violating the Mann Act for transporting a minor across state lines. Later, when he bought a restaurant, he was accused of installing cameras in the women’s restroom.) He told me of an incident last year during his class on the history of opera, in which he’d quite innocently played a clip of the processional scene from a staging of Aida, thinking he’d teach his students about what he calls composer Giuseppe Verdi’s “magnificent music.” But some were too repulsed by an actor appearing in blackface to hear what he had to say about the melody.

“Of course, it’s absolutely essential to understand the fact that there was blackface … but to not be able to rally to that magnificent music because of imposing one set of rules and values on another time is problematic for me,” Budds says. “I certainly want everyone to understand the history of discrimination in American society, and I go out of my way to make sure that people understand things like that. But to automatically disqualify a powerful musical experience because of some of those social circumstances? I don’t exactly know how to deal with that yet.”

Constance Penley, former chair of the film and media studies department at University of California at Santa Barbara and past director of the Carsey-Wolf Center says she makes a point to “not give trigger warnings” in her classes—especially the one about pornography—because her lesson plans should speak for themselves. But she also is scrupulous when it comes to vetting hires for all positions in her department, not just faculty.

“We can’t have someone in the department who is not going to comfortably support us in showing everything,” says Penley, adding that the purpose of showing all of these films is the classroom discussion that builds around them.

This isn’t to say that academics haven’t had their own “never meet your idols” moments. After all, they dedicated their lives to covering these art forms because they love them and, sometimes unfortunately by default, the people who created them.

Christine Acham, a cinematic arts associate professor at USC, has lectured and written about Bill Cosby’s impact on contemporary cinema and television. But, despite being a self-professed “gigantic [Cosby Show] fan for the longest time,” Acham says her appreciation for Cosby waned when she became more aware of his sometimes reactionary political values and the way she feels he had been “de-historicizing and de-contextualizing the ways in which the Black community has had to struggle.” By the time Hannibal Buress’s standup routine and the many sexual assault allegations against the legendary comic rolled around, she’d shoved her once-cherished photo of the two of them to the back of a desk drawer. Yet she still teaches The Cosby Show in her class.

“I think that the way I felt about it is that he is a part of African-American television history. We cannot deny it, and we cannot erase him from that history,” says Acham, acknowledging that her students have a vastly different reaction to The Cosby Show than she did watching it in her living room during its original run. But, she says she can help them contextualize “that he really sort of sold himself as the most respectable Black man, and the father of America, and he was able to kind of judge African-American society and what they were doing at a certain period in time; and was very vocal about that while he was simultaneously abusing women.”

The #MeToo movement is also coming at a fortuitous time in academia, as essays and studies in recent years have called for the hiring of more diverse faculty (which would, theoretically, give light to more diverse subjects). This might be just the kick in the pants educators need in order to diversify which artists they put on their syllabi. J-L Deher-Lesaint, the assistant professor and co-chair of the English, speech, theater, and journalism department at Chicago’s Harold Washington College says that he’s as “mindful as possible to include more works by women, in film or literature” and has “taught classes on doing and undoing the male gaze across many sexualities and sexual identities.” He adds that, “I won’t stop mentioning Allen, Hitchcock, Weinstein… and the like, but I will always provide students with the full story for them to decide how problematic it might be for them to admire an artist’s work.”

After all, as Sarah Erickson, an assistant professor of communications at San Antonio’s Trinity University argues, what better place than college to engage in these conversations? It’s impossible to say exactly how many schools have seen changes to dialogues on campus or in the classrooms, but it seems to be working for the ones that are.

“College is a place where students can talk about tough issues like those that are brought up by the #MeToo movement in a relatively safe environment,” says Erickson, who has also discussed the significance of The Cosby Show to students at her predominantly white institution. “I don’t think I can, as a media scholar, pretend like The Cosby Show didn’t exist. And I don’t think I can pretend like the #MeToo movement doesn’t exist. So I try to have a dialogue with them about it.”

Specifically, Erickson says, she’s had a group of (all-white) students come to her to ask how they can respectfully present “research on Black audiences to a classroom of white students” and talk about what a “game-changer in representation of black families when we now know all this stuff about Bill Cosby.”

“A lot of what I recommend to do is turn it back on the class and say, ‘’Hey, now we know all this other stuff. What do you make of it?’” Erickson says, adding that while there were certainly students who do not want to look at any images of Cosby in the classroom, she was able to have a discussion on accepting “that a television show is not created by one person alone.”

“If we totally dismiss everything about this, we’re not only dismissing how important it was for audiences, but also how important it was for the lives of the other people that worked on the show,” Erickson says.

The hope, in all these cases, is for the students to become the teachers and it seems to be working. Deher-Lesaint says his students at Harold Washington are captivated when they learn about, say, Polanski’s rape of Samantha Geimer—especially when adding the context like his wife’s murder by the Manson family, his Jewish childhood surviving a concentration camp in Auschwitz, or that his victim has tried to put the case behind her—or when he says he shows how Alfred “Hitchcock’s fetishism, voyeurism, personal paranoia, misogyny … wove their way into his work.” Penn State’s Rodino-Colocino says she’s particularly seen changes in her male students who have adapted this class discourse and news reports to their own lives.

“Men get that they need to learn new behavior and language around consent,” Rodino-Colocino says, adding that the school invited football player Wade Davis to host a discussion on how not to commit sexual assault. She noticed that some of the guys in attendance “wanted to discuss what language they could use so that they could see if their partner would consent to sex and not come off as creepy.”

But, in addition to the marches, hashtagging, and thesis-paper topics that have been exploding on college campuses as responses to the #MeToo movement, perhaps students will also start protesting with their pocketbooks. University of Florida’s Selepak points out that his students—the youngest of whom were born in 2000—may not have recognized the names Harvey Weinstein or Kevin Spacey before now.

“What is needed beyond awareness is action,” Selepak says. “We will soon see what the effects of the movement truly are depending on whether those who engaged in acts of harassment and assault are eventually allowed to restart their careers and see no repercussions for their actions other than a temporary dismissal from the spotlight.”

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.