Reflecting on her childhood fear of the serial rapist-murderer, who was recently arrested in her hometown, the actress and writer wonders how her parents were able to ultimately make her feel safe.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

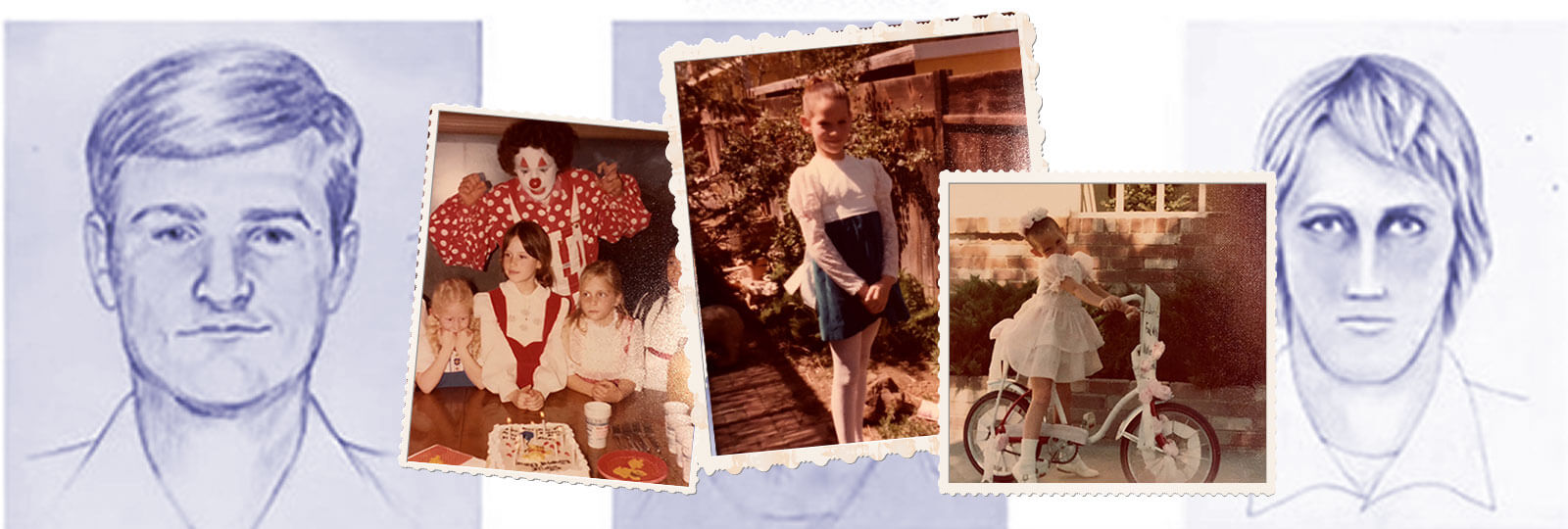

In 1976, the year of the Bicentennial, I was in the second grade. It was a year that seemed to me consumed by two topics of conversation: the Founding Fathers (patriotic swag abounded everywhere) and a monster that people referred to as the “East Area Rapist.” I was particularly interested in the latter because I lived and went to school in the east area of Sacramento, where the violent serial predator was breaking into people’s suburban homes and raping women, regardless whether children were present.

At 7, I wasn’t clear exactly what rape was—my understanding of sex was hazy at best—but I knew it was bad. I also knew that it was something that was happening to women. Women alone with their children in the house. Women like my mother.

My father was a musician who supported our family by playing piano late into the night. Since he was also blind, my mother drove him to work after family dinner in the early evening, and then would go back and pick him up when he finished, around two in the morning. My older sister and brother and I usually accompanied them for the drop-off, and when it was time to get him, my mother would carry each one of us out to the car individually, half asleep, with pillows, blankets, and stuffed animals. Both of our parents carried us back into the house upon our return. Every single night. During the time in between pickup and drop-off, my mother was alone in the house with three young kids under the age of 12. We had no house alarm, no gun—the closest thing we had to guard dogs were a small, hyperactive poodle and an overweight Chihuahua named Chili Beans.

We also didn’t have around-the-clock news then, and never subscribed to the local paper since my father only read braille and my mother was too busy cooking, gardening, and driving us to school and to our various extracurricular activities to sit and read the paper. She always seemed to be in perpetual motion. But the stories of the East Area Rapist’s crimes reached our ears in lurid detail despite the news blackout. The mothers gathered on street corners in our little cul-de-sac neighborhood and chatted about the latest attacks in low voices. If one of us asked a question about the East Area Rapist, the subject was quickly changed to something benign, like American tennis champ Chris Evert’s latest defeat over the Australian tennis ace Evonne Goolagong (whose name sounded like a dessert to me). But later, at school, we would recount the gruesome details to each other.

“Did you know he put plates on them and said he would kill them if they fell?”

“He uses shoelaces to tie them up!”

Talking about the “East Area Rapist” was like talking about the boogeyman, except that there wasn’t any lingering doubt about whether he was real. I still believed in Santa Claus, so the idea of a man coming into your house uninvited was hardly beyond the realm of possibility.

When I read on April 25 that a suspect had been arrested in Citrus Heights, California, the hair on my arms stood up. In 1976, when he committed his first known crime, I was living with my family at 7554 Garden Gate Drive in Citrus Heights just a few miles away. My grandparents lived in Auburn at the same time the suspect, Joseph James DeAngelo, lived and served on the police force there. Sometimes, when I visited them, they would take me for pancakes at the Denny’s where DeAngelo’s mother supposedly worked.

DeAngelo was fired from the Auburn police force for being accused of shoplifting dog repellent and a hammer from a Pay N Save in Citrus Heights. He didn’t live in our town then, but he committed many of his first rapes in the county, and then would later choose to settle down in a house four miles from my childhood home, blending into the quiet suburban town, and into the nondescript grandpa on the precipice of retirement. Of course I didn’t know any of these details then. Back in the 1970s, the East Area Rapist was nameless and faceless to me. Except for the few police sketches, no one knew any real details. He was a terrifying mystery who became a chimera as time went on, and the case grew cold.

Strangely, despite having lived with the threat of a ruthless criminal striking continuously in such proximity, I felt safe. I suppose this is a testament to my parents and the psychological security they provided me. I was allowed to ride my bike with my friends to the 7-Eleven a couple of miles away. All of the kids I knew back then ran around the neighborhood unsupervised. We would climb over the fence and into the creek and pick wild berries behind our house, walk in and out of friends’ houses unannounced, run around the overgrown field of weeds at the Lutheran church down the street, as long as we were home in time for dinner. If we weren’t home by sundown my father would stand out in front of the house and bellow each of our names. His resonant voice echoed throughout the twilit neighborhood and sent us scrambling home.

Now I suppose they would be called “free-range parents.” As a mother of young children myself, who tries my best not to “helicopter” my own children, it’s hard to fathom the freedom we were given as kids, especially considering the danger lurking nearby.

“Weren’t you scared?” I asked my mother recently.

“Sure I was,” she said. “But what are you going to do? You have to live your life.”

“Did you consider getting a gun?” I asked.

She scoffed. “No, of course not. I would never have a gun in the house.”

I asked what her plan had been for the East Area Rapist.

“Oh, I don’t know,” she said. “We kept our doors locked.”

“And we got an automatic garage-door opener,” my father, who had been listening, added.

“I don’t think we got that until later,” my mom said.

“That’s why we got one,” he insisted.

My parents squabbled about when exactly they got the automatic garage-door opener and then finally agreed that, yes, the garage-door opener was thanks to the East Area Rapist. But I only remember our car being parked in the driveway.

You have to live your life. This sentence of my mother’s was not really that surprising to me. It’s always been more or less her philosophy and I believe it was born out of someone whose life hasn’t always been easy. She didn’t come from wealth, wasn’t given a fraction of the opportunities she gave her own children or the myriad I give mine. People often say that parents do their best, and I think for the most part that’s true. But it so happens that her parents’ “best” just wasn’t very good. In fact, it was pretty dismal. Her father was a black-out alcoholic and her mother, a compulsive gambler. She wasn’t even taken to the dentist for eight years as a child. Somehow, (I don’t even know for sure how), my mom survived. She overcame the physical abuse and severe neglect, by her wits, her intelligence or just an innate sense of survival. My mother spotted my father across a room when she was 18 and said she knew right away that she wanted to make a life with him. Nothing was going to take that life away from her. While that certainty bolstered my sense of security I’m not suggesting it had anything to do with our home not being one chosen by the East Area Rapist. That was just luck. Random, dumb luck.

Not long after I found out about the arrest, my sister Beth texted me to ask if our mother had seen the news. I was having dinner with our mom at the time and texted back that I had been talking to her about it all day and that at first my mother wasn’t even sure she remembered him. My sister had been following the case for awhile, knew when Michelle McNamara—the late author of I’ll Be Gone in the Dark who’d spent years investigating the rapes and murders—renamed him “The Golden State Killer” and was shocked that the details weren’t as fresh in our mother’s mind as they were in ours. “Everybody around Sacramento including me was terrified of him in the ’70s!” she texted.

“There was a cannibal who was caught not far from your school,” my mother mused. “I definitely remember him. But they caught him right away.”

It’s a wonder they didn’t put Xanax in the water along with the fluoride.

In 1978, my family moved from Citrus Heights to North Hollywood in Southern California. We lived in an apartment for a year, which is where I stopped believing in Santa Claus after my mom had a mini-nervous breakdown trying to get all of the Christmas presents wrapped by herself. (Truthfully, I had already stopped believing while we were still in Sacramento, but it was then that I stopped pretending to believe for my mother’s sake). I wrapped presents with her until late into the night, and it was the first time I remember seeing my mother as a person, and not just my mother.

Eventually we moved into a house with a swimming pool surrounded by palm trees, across from a used bookstore and a Pioneer Chicken restaurant. Memories of the East Area Rapist faded into the background as I grew into a teenager. It wasn’t until much later that I’d learn the East Area Rapist started attacking people in Southern California as well. I assumed that those were committed by someone else.

A new era dawned at the beginning of the ’80s: the American hostages in Iran came home. I became obsessed with New Wave music, Ms. Pac-Man, convertible cars, Ray-Bans, drinking coffee at Dupar’s diner, and the color pink. I drove up and down Ventura Boulevard with my friends listening to Bananarama and then back up to the top of Mulholland Drive. I danced at Florentine Gardens, went to the movies, stayed up all night, acted in movies, and then grew up and moved away from California altogether.

I’m relieved that this particular monster was finally caught, a proof that in some way our justice system still functions. I may not have been an anxious child, but I confess I have grown into an anxious adult. I stay up late scrolling though the news wondering when we will all be able to exhale and just live our lives.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.