Movies

How To Fix the Romantic Comedy

Historically marketed to women, and often problematic, the most profitable film genre needs a face-lift if it’s going to win over audiences in the #MeToo era and beyond.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I first saw Love Actually in the theater with my friend Kate. We were 22 years old, single, and well-versed in the rules of rom-com: ‘Tis better to be a “singleton,” to borrow a word coined by Bridget Jones, than settle for a non-soulmate who looks nothing like Colin Firth.

We bought popcorn and in the silent seconds before the movie began, stopped our loud chewing and held the buttery kernels in our mouths so as to not attract attention. We looked at each other and laughed sheepishly. We kept laughing throughout Love Actually, which had its highlights, most notably a scene-stealing turn by a lowbrow brilliant Bill Nighy. And yet, this pleasant and pretty film populated with pretty people fostered a feeling that deeply unsettled me, leaving a sour aftertaste. Later, in the parking lot, Kate lamented, “What about Laura Linney?”

What about Laura Linney indeed. The actress’s character, a competent professional woman who selflessly cares for her mentally ill brother, was given the short shrift by writer-director Richard Curtis: Her creepy boss, overstepping boundaries he pretends not to know exist, encourages her to date the sexy graphic designer office crush (Rodrigo Santoro, model) for whom she pines. But then! Following a successful night out with the object of her affection, her brother phones, interrupting an intimate moment. Office Crush walks off like he’s seen a ghost, thereby ending the relationship before it even began. According to the romantic comedy playbook—a genre that hinges on the pursuit of love as the ultimate life-fixer—this was a flat-out failure. Laura Linney didn’t even end up with a platonic best friend.

The boys of Love Actually are the winners here—they all find love—and they fully embrace their privilege to woo female employees of much less power and means, enshrining an unequal dynamic that doubtless fills Mike “Handmaid’s Tale” Pence with delight. It’s basically a fairytale for the patriarchy.

Love Actually premiered in 2003, a weird time for women. Back then, especially if you were 22 and aching to be as desired as Britney Spears in a backless top, it was uncool to call yourself a feminist, which translated to “man-hater” among college bros who cruelly mocked Take Back the Night rallies. Romantic comedies have always held up a mirror to society, reflecting back the dynamics between men and women throughout history—and how gender roles have evolved. But they’ve never quite gotten them right. The way to sustain the romantic comedy—endangered at the 2018 multiplex despite the popularity of infrequent sleeper hits such as The Big Sick—is to modernize it for a younger, multicultural and open-minded audience of hopeful romantics who crave stories about love, but rarely, if ever, see their experiences expressed on-screen. The solution is simple, yet has eluded Hollywood far too long: Greenlight more movies with writers, directors and actors of different backgrounds who can bring the illuminating and inclusive perspective needed to refresh the romantic comedy.

The innuendo and conservatism of the 1950s was officially out of fashion by the time the feminist movement of the 1960s and ’70s swept America, coinciding with the demise of the studio system and the rise of auteur filmmakers who made provocative movies about relationships where traditional happy endings no longer applied. See: Annie Hall, An Unmarried Woman, The Graduate. And 1972’s The Heartbreak Kid, directed by Elaine May, that subverted the rom-com formula to explore life after the meet-cute: the dark side of marriage, and what happens when Happily Ever After fails to live up to the hype. During this period, when young Americans questioned institutions of every kind, when women walked out on their husbands in unprecedented numbers, when the conversation surrounding sexual politics drew attention to inequities in male-dominated popular culture, the conventional romantic comedy appeared wildly out of place. Just as the early feminist movement notoriously excluded lesbians and women of color, romantic comedies have projected a very specific image of who deserves to find love. Of the hundreds of studio romantic comedies produced in past years, virtually all have centered around white, heterosexual couples—many of whom have sidekicks-of-color whose main function is to serve as a star’s sounding board. Like Laura Linney, these characters are fated to be the bridesmaid but never the bride.

1989 was the year the romantic comedy changed—or was supposed to, anyhow. The Reagan era brought political and cultural backlash against women—and advances made during women’s liberation—that weaved its way into movies from the dramatic (Fatal Attraction) to the romantic (Overboard), wherein career witches were killed and rich-bitch shrews tamed, thereby easing the anxiety of men who resented women for not staying in their lanes, aka the kitchen. When Harry Met Sally, starring Meg Ryan in her breakthrough, defining film role, focused on a career woman who believed, unlike her romantic foil (Billy Crystal), that men and women could be friends without sex getting in the way. The collaboration between director Rob Reiner and screenwriter Nora Ephron—whose biggest priority was to write “about two strong people finding their way to love”—created the blueprint for a second golden age of romances that restored the balance of the screen couple along with the old-school happy ending while mining contemporary truths about men and women for laughs. This movie made people feel good—also restoring their faith in love—and studios greenlit a rom-com revival that produced a number of hits and misses until petering out as superhero and fantasy flicks took over the international multiplex.

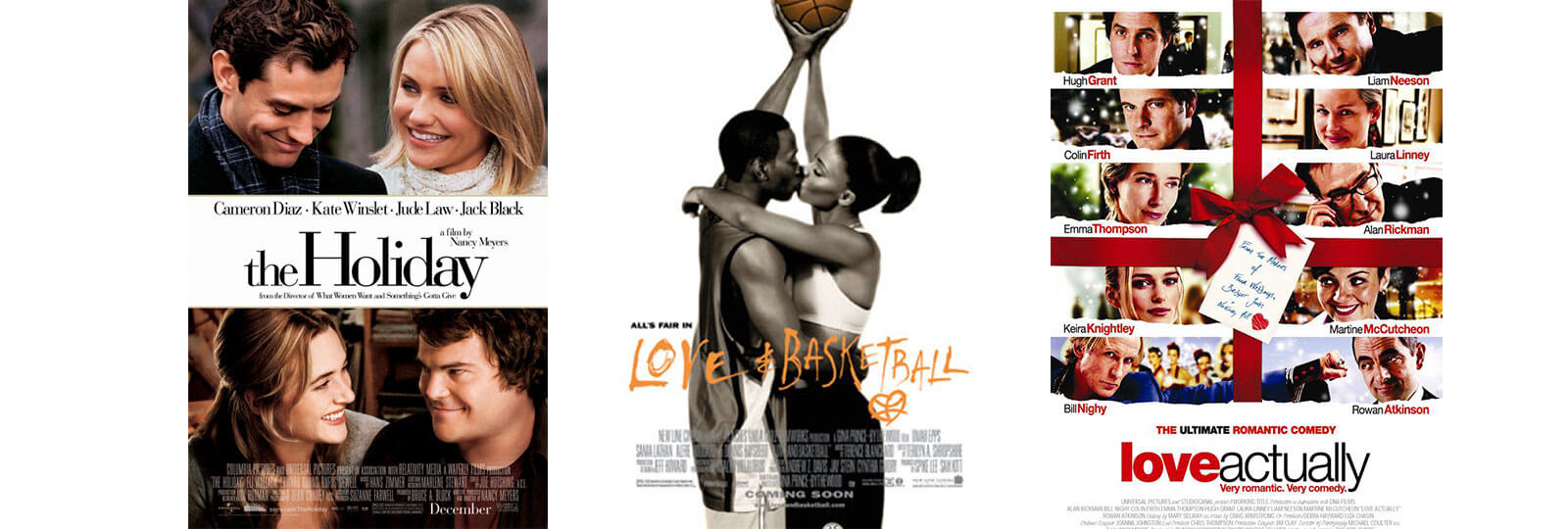

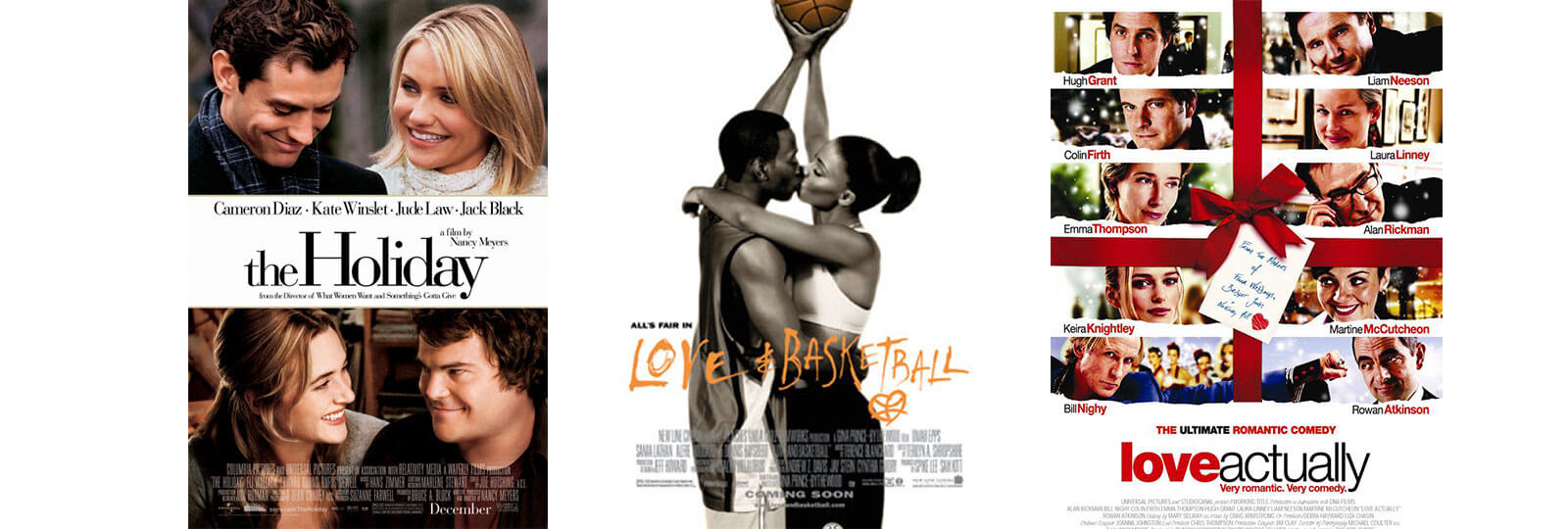

Though Ephron and another successful woman filmmaker, Nancy Meyers (It’s Complicated, Something’s Gotta Give), infused the romantic comedy with a female point of view that felt refreshingly authentic—look, if you’re going to make films about women for women, you might as well hire women to make them—both directors overlooked people of color in casting their greatest hits. Ephron, who did cast Dave Chappelle in his charming, be-turtlenecked role as sidekick-to–Tom Hanks in You’ve Got Mail, socialized mainly with white people from her Manhattan/Montauk/Malibu milieu; her films reflect that experience. Perhaps she didn’t think about racial diversity, nor see it as essential. And that’s not just Ephron. That’s Richard “Sexism Actually” Curtis. That’s Judd Apatow, who wrote and directed the 21st-century “classics” The 40-Year-Old-Virgin and Knocked Up, in which Katherine Heigl had to quit her job to have a baby with her one-night-stand: stoner Seth Rogen. And he got all the jokes.

That’s Hollywood. Representation matters, and the romantic comedy—beloved by everyone, not just the straight, white women whom marketers have long targeted narratives of straight, white love—should recognize and reflect the diverse rainbow of hopeless romantics aching to see themselves on screen, not to mention the actors, writers and directors of color who could make the next When Harry Met Sally if given the opportunity.

And it’s not that the stories and stars weren’t out there, it’s that they were never afforded the chance. The hugely successful Black-targeted rom-com genre (and it should not be its own genre, but a part of the larger one), has raked in hundreds of millions of dollars for Hollywood. Brown Sugar, starring Taye Diggs and Sanaa Lathan–the Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan of Black-targeted rom-coms–made nearly $30 million its opening weekend–in 2002. Boomerang, starring Eddie Murphy, Martin Lawrence, Robin Givens, Halle Berry, and David Allen Grier, is one of the most quoted (and now memed) movies in modern history, putting the actual comedy in rom-com.

Perhaps the most underrated–albeit entirely beloved by those who know it–is Love & Basketball, the phenomenal 2000 love story written and directed by Gina Prince-Bythewood, starring Lathan and Omar Epps. It was one of the best-reviewed movies of that year, making stars out of its leading actors. What’s more, Lathan and Epps got equal billing, and that’s no accident: Prince-Bythewood, truly invested in Lathan’s character, ensured that she showed up in the script as a fully-fledged human and not an object or male projection. And as the one calling the shots, the director also reserved the power to protect her character, a tough yet vulnerable basketball powerhouse, during the filming process. She said in a recent appearance at the British Film Institute, “There’s a stereotype about female athletes and who they are and what they’re like that I wanted to knock back and show that you can love sports, you can be tough but you can also be feminine. And that you can fall in love and that you can have it all.” If a man were in charge, the tone of the movie—its emphasis on the female perspective—might have changed entirely, at the expense of Prince-Bythewood’s vision.

Not surprisingly, the game-changing When Harry Met Sally inspired Love & Basketball‘s delightfully predictable plot about friends-turned-lovers, according to Prince-Bythewood. Ephron’s alter ego, Sally Albright, was complex and interesting, and Reiner allowed her to be; in a rarity for a male director, he gave Ephron a seat at the table and encouraged her to tell Sally’s love story from her own idiosyncratic point of view. The result: A character who inspired other would-be romantic comedy writers and faked the most famous orgasm in cinematic history—one that caused women to collapse with laughter and men to squirm in their seats. Later, when Ephron watched the mean-spirited, misogynistic director Herb Ross mangle her script for the Steve Martin flop My Blue Heaven, she realized her positive experience with Reiner had been kind of a fluke.

Creative control is everything, and since men continue to hold the reins of power in the movie business, the support of male allies can make or break a career. (I am reminded of my conversation several years ago with Oscar-winning screenwriter, David S. Ward, who said peers were having trouble finding someone to direct a Tupac Shakur biopic. I suggested Prince-Bythewood, who had just released the wonderful romance Beyond the Lights, but he dismissed the idea. He said they wanted a man to direct it. I think about this a lot. And I especially think about how he might have responded differently to me, a journalist, following the fall of Harvey Weinstein and the movement against sexual harassment in Hollywood. As Time’s Up co-founder Shonda Rhimes argued: “It’s very hard for us to speak righteously about the rest of anything if we haven’t cleaned our own house.”

Women have always found more opportunities working in television, where the rom-com has migrated in recent years. Writer-producer Rhimes (brilliant at casting) has built an empire with watercooler TV series that offer juicy roles, with steamy storylines, for Kerry Washington, Viola Davis and Sandra Oh. Mindy Kaling (obsessed with You’ve Got Mail) graduated from The Office fan favorite to writing and starring in her popular romantic comedy, The Mindy Project, which ended its five-year run last November on Hulu. (Kaling will soon be seen opposite Reese Witherspoon and Oprah in Ava DuVernay’s A Wrinkle in Time.)

More women like Kaling need to be granted opportunities, on TV and in film, in order to push the romantic comedy to new creative heights—and broaden the audience for the genre by representing people of all backgrounds. And that includes LGBT stories. Call Me By Your Name, a sexy, intellectually satisfying slow-burner co-starring Armie Hammer and Timothee Chalamet, is hands down the most romantic film I’ve seen in years. And Hammer as the most fire screen god since Brad Pitt in Thelma and Louise. Gay romance? Irrelevant. This film is about yearning and desire and stolen glances and first love. But despite what Hollywood will lead you to believe with its barrage of accolades for the deserving film, it is not the first same-sex love story worth celebrating. Other gems suffered from lack of exposure, like The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love by Maria Maggenti, But I’m a Cheerleader, directed by Jamie Babbit, and Saving Face by Alice Wu.

In recent years, a handful of winning rom-coms have pushed the envelope—but we can do better. Obvious Child, written and directed by Gillian Robespierre, stars Jenny Slate as a comedian who becomes unexpectedly pregnant (and omg: gets an abortion without being made to feel guilty about it!); it’s a Knocked Up from the pen of a woman, and this time, the girl gets all the jokes. Silver Linings Playbook is a sharply funny, deeply felt story about second chances that humanizes mental illness, yet it revolves around the love between straight, white characters played by Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper. (Imagine if Shonda Rhimes, or Lin Manuel Miranda, or a casting director with imagination, had cast Silver Linings. It goes without saying that an age-appropriate actress should have replaced Lawrence in her role as a world-weary widow who appeared to be at least 19 years old. At the time, nobody really batted an eyelash, and Lawrence walked away with an Oscar.)

2017’s most successful rom-com, The Big Sick, proves the romantic comedy can evolve in fresh, inclusive ways with an interracial love story. Like When Harry Met Sally, The Big Sick was written by a comic actor (Kumail Nanjiani, who also stars) and a witty screenwriter (Emily V. Gordon, Nanjiani’s wife). Gordon enhanced the screenplay with amusing, specific observations from her real life and relationship with Nanjiani, a Muslim man who was born in Pakistan and moved to the United States at age 18. The result: The No. 1 ranking last year at the specialty box office, a category for films that skew small, experimental and independent, and often cross over into mainstream success. The accolades include an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay and the Women’s Film Critics Circle honor for Best Screen Couple, featuring Nanjiani the lovesick immigrant and Gordon stand-in Zoe Kazan, who’s allowed to portray a human being and not a male fantasy. It’s the way it should be. But it’s the exception to the rule.

“The good (romantic comedies) are a good mix of escapist entertainment but also character studies and … also about something else,” Nanjiani told me at December’s SFFILM Awards Night, where he and Gordon were honored with a screenwriting award. For example, he said, When Harry Met Sally addresses the universal issues of sadness and loss, and also the realities of aging and the shifting priorities that come with it.

Reiner and Ephron and Nanjiani and Gordon knew that story is the backbone of a great romantic comedy; if the script is excellent, that gives filmmakers the freedom to experiment with casting and alternate visions of love that don’t fit the mold. The mission, should the powers-that-be choose to accept it: Love stories between people who are neither white nor straight should be so common as to be completely ordinary. The romantic ideal of the pretty, self-deprecating white girl and cute, rascally white guy is a tired trope, a formula that’s lost its fizz. Now is the time for industry leaders, under pressure since #OscarsSoWhite, #MeToo and Time’s Up to ditch the empty talk and finally open doors to women and people of color. That means funding projects for and by women and people of color and buying original scripts from them. Imagine Issa Rae, one of HBO’s brightest, most exciting stars, take on a big-budget romantic comedy; or Lena Waithe, creator and director of the Showtime’s equally funny and heartbreaking The Chi, penning a poignant love story that happens to feature two women. Like Mindy Kaling, these women aren’t an anomaly; they’re the future.

A rom-com landscape that’s truly diverse and rich in both story and experiences is the happy ending the genre needs.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.