Sexual health

Your Vagina, Explained

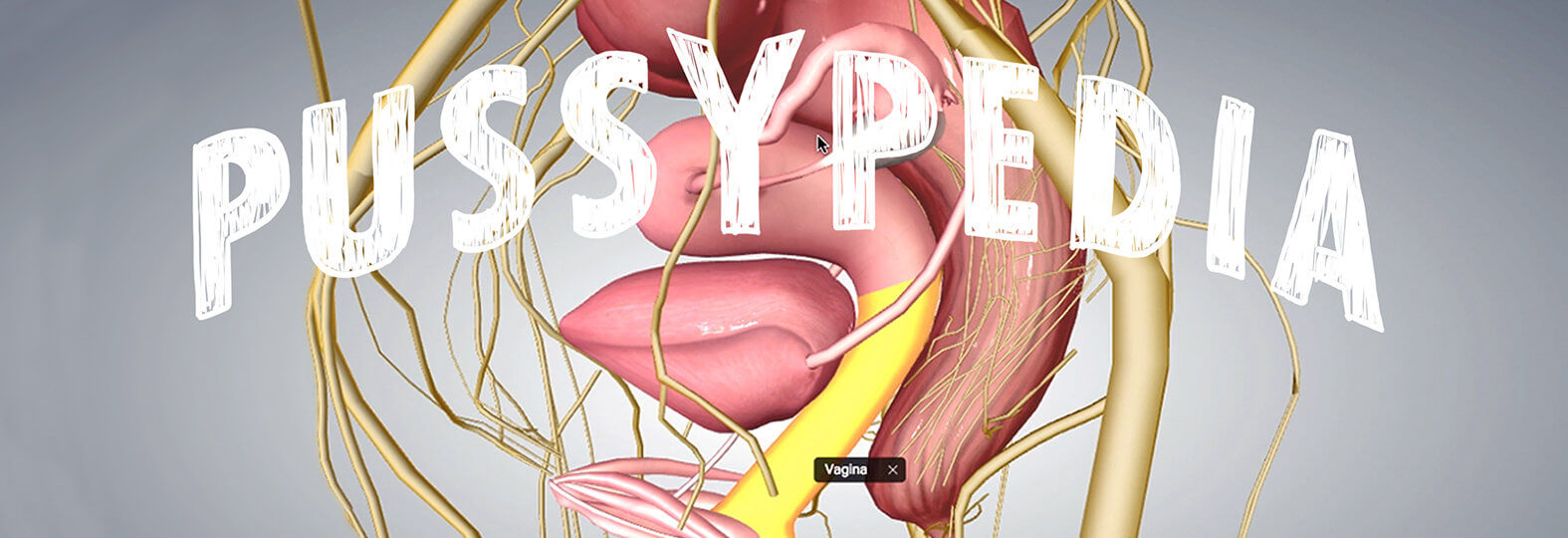

“Pussypedia,” a new Bilingual, Online “Encyclopedia of the Vagina” is here to answer all your questions and make you feel damn good about your lady business.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

In 2018, it’s tempting to think that our collective understanding of the female body has vastly improved since the Ancient Greeks’ crazy “wandering womb” theory, or since Freud declared the clitoris a tiny, “inferior” version of the penis.

Sadly, anatomical misinformation seems rampant as ever. Fake pregnancy clinics across the U.S. spread bogus claims that abortion causes breast cancer. Celebrities urge women to shove $66 jade eggs up their vaginas. Twenty-three percent of U.S. public schools teach abstinence-only sex ed. The problem is worse in Latin America, where many schools don’t teach sex ed at all.

Enter Pussypedia, a bilingual, online “encyclopedia of the vagina” that aims to correct centuries’ worth of ignorance surrounding femme sexual health. Illustrated with an interactive 3D model of the vagina—which looks a bit like a creature out of Pan’s Labyrinth—Pussypedia will feature encyclopedia entries on everything from transfeminine and transmasculine vaginal health to menstruation, masturbation, STI prevention, contraception, and abortion.

Mexico City–based journalist Zoe Mendelson started the project after Googling, “Can all women squirt?” The search results didn’t answer her question conclusively, but she did discover that everything she thought she knew about G-spot orgasms was wrong. Hoping to enlighten the sisterhood, Mendelson recruited two friends—Jackie Jahn, a Harvard School of Public Health Ph.D. student, and artist Maria Conejo—to help create an online hub of meticulously-sourced information about pussies (their preferred term).

After raising more than $22,000 on Kickstarter, Pussypedia is slated to launch later this year. In both Spanish and English, it will be freely accessible to anyone on the internet, including the estimated 50 percent of men who can’t identify a vagina on an anatomical diagram. DAME talked to Pussypedia’s creators about the wonders of clitoral bulbs, how their project relates to #MeToo, and why they’re embracing the P-word.

Why does the world need Pussypedia—and especially why now?

Zoe: If you start with the basic premise that knowledge is power, then we need more knowledge about our own bodies. It’s a simple equation. Knowledge is the tool to assert control. If we can’t control our own bodies, we can’t fully own them and if we don’t own them, who does? The internet is too far along to not have a good amount of reliable, accessible information about vaginas. It’s ridiculous.

Maria: It’s unfair that it’s 2018 and we aren’t aware of how our bodies work. How we can be in control of our own sexuality and birth control? I think the majority of serious problems in my country, Mexico, are due to a lack of education in general. When we talk about sexual education in Mexico, it’s a scary thing. It’s always been avoided or treated as something bad, a sin, because of religion and macho culture. Making certified information free and accessible to everyone is one solution to this problem. We need to educate ourselves.

This may help to prevent diseases, unwanted pregnancy, and create a place where you can find answers and talk about your intimate issues with trust.

Zoe: There’s also a power imbalance in that we don’t know about our own anatomies as much as men know about theirs, especially when it comes to pleasure. A lot of women don’t know how to get themselves off. Most women probably don’t know what their clit looks like. Some don’t know what any clit looks like. They don’t know where their own erogenous zones are. And because we’re ashamed, we don’t take the time to explore it.

What role will Pussypedia play in the #MeToo movement? How do you think the culture of silence, taboo, and misinformation surrounding women’s anatomies is linked to the culture of silence surrounding sexual harassment and assault?

Jackie: First, I want to make clear that the onus of changing the culture of sexual assault and harassment is on men, not women. Pussypedia is a resource for people with pussies and is not meant to be a solution to the silence that enables sexual assault. I do, however, think the feminist spirit of the site will encourage readers of all genders to respect pussies and women’s health.

Zoe: Sexual violence comes from men, but there are things [women] can do to help fix the problem. One thing we can do is to own our own sexuality. We have to be able to say “yes” in order for no to mean no. When we’re ashamed of our bodies and our sexualities, we can’t vocalize what we do want and what we don’t want. That’s where our responsibility comes in to fix sexual dynamics between men and women. We need to be able to say “Yeah, I want sex,” and one step toward being able to say yes is not feeling freaked out and disgusted and ashamed of our vaginas.

2017 was the year the word “pussy” went mainstream, arguably thanks to the so-called “pussy tape” and the ensuing wave of pussy hats and pussy-grabs-back sentiment. Why should we reclaim or reappropriate “pussy”?

Zoe: Because first of all, fuck the idea that Trump is gonna own the word pussy. Fuck that.

But also because there’s no word that we use that refers to the variation of anatomies, or to the entire [area]. A vagina is just the canal. When we refer to everything as the vagina, it’s not comprehensive.

Also, the word vagina comes from the Latin word “vāgīna,” which means sheath—that thing you put a sword in. So we kind of refer to our pussies as “the thing you put a penis in.” Why focus on the one part where the penis goes in?

And people have tons of different variations of parts. Deciding that “pussy” is just gonna mean all those variations makes it a more inclusive term.

A lot of people still don’t like the word “pussy.” Why?

Jackie: People don’t like that word because the demeaning original connotation is still real for them. I like that word because it’s what a lot of people actually call it. The “pussy” part of Pussypedia is people’s real language/experiences/knowledge of their own bodies, the “pedia” part is sexual health research.

Why is it still so hard to find reliable, comprehensive, accessible information about our bodies, even with the whole internet at our disposal?

Jackie: Too many sexual health campaigns and websites 1) shame femmes for having sex, 2) assume queer women don’t get STIs, 3) are written for academic and not lay-people audiences (and are behind journal paywalls), and 4) are scattered across the internet and hard to find. Pussypedia plans to change that.

Maria, what is the state of sexual education in Mexican schools? What are some particular obstacles Latinx people face when seeking information about sexual health?

Maria: Well, there is a lack of quality education in Mexico, so sexual education is almost nonexistent. When I was a child we used to have a class called “Values” and another class called “Health” where we talked about the body as something biological. Sexuality was framed as only being for reproduction. I wish I had learned earlier that I’m allowed to feel pleasure and don’t have to feel bad about it.

In my high school, I was always accused by the principal and other nuns of having a body that distracted boys. They said I needed to cover it, so I was asked several times to buy new uniforms. One time, I brought a feminist magazine to school, because I wanted to photocopy some artistic photos of nude people. A teacher took it and gave it to the principal’s office. Someone there opened it and found an article of how to give oral sex to a woman (that actually was very well explained). They called me and sent me to the school psychologist. This person told me that I had a sexual disorder and that I was being promiscuous. Maybe that can give you a picture of how sexual education is in Mexico—and I’m talking like middle-class education that I was privileged to have. In public schools, they actually don’t care about sex ed. That’s why we have a lot of teenage pregnancy, too.

Asking questions about your body has always been a matter of shame. So, where do you go to find the answers? On the internet, but sometimes it isn’t that reliable.

How do you plan to make this site inclusive for gender non-binary and trans people?

Jackie: We’re working with consultants to advise us on how to make the site a place GNB and trans (and disabled!) people want to visit. We’re also having internal discussions about our language and framing—to avoid defining femininity and womanness by body parts, and making our visuals more inclusive.

Jackie, as the research lead on this project, how are you sourcing your information?

Jackie: When Zoe first told me about her idea for a free, online, bilingual encyclopedia about vaginas, it struck me as a way to put my years of public health training to immediate use. Generating internet content for a mass audience is way outside my researcher comfort zone, but I wanted to contribute because I feel a deep responsibility to share the benefits of my scientific literacy. My role has been to examine the published literature, make sure all scientific claims are accurate and cited, and shaping the messaging to avoid the shaming/transphobic/heteronormative missteps of some previous public health work.

How does knowing scientific information about your body translate into empowerment and more self-confidence?

Jackie: It doesn’t always! A lot of sex-ed experiences can have the opposite effect. I think the key is in how the information is framed—with wonder, appreciation, frankness, and relatable narratives.

Zoe: When we don’t know what’s going on with our bodies, we can’t take care of them and our health suffers. Health is a necessary condition for power in a fundamental, practical sense. When we don’t know about our bodies, we are more susceptible to the shame that advertisers purposely instill in us to create demand for their products. That often leads us to buy and use products that damage our health.

If we consider ourselves equals, why do so many people with pussies readily give but never ask for oral sex? Because they think their pussies are gross and so they fail to believe they are equally deserving. When we think we are gross, we think we are less, and we do not assert our needs or desires. Shame means we lay our power down at their feet.

Or take birth control. Multiple doctors told me I was totally imagining the side effects. They insisted it was the most tested and harmless drug ever. But I felt terrible. I was fatigued, gained 10 pounds, and felt completely emotionally psychotic. After a few years I decided, against my doctors’ insistence, to quit birth control. Those problems stopped. Now they’ve finally started admitting the side effects of birth control. But when you don’t have knowledge, you are at the mercy of “experts” to make informed decisions. When you can’t make informed decisions, you have no power.

What did you learn about your own anatomy while researching this project that you hadn’t known before?

Zoe: That the so-called ‘G-spot orgasm’ and ‘clitoral orgasm’ aren’t actually two separate kinds of orgasms—they both stem from one system of nerves being activated. The idea of “I don’t come that way” or “I can’t come that way” is wrong. It’s all one thing.

Jackie: Bacterial Vaginosis can pass between pussies, OMG!

Zoe: And people just don’t know about the clitoral bulbs! They’re these two bulbs, part of the clitoris, on either side of the vulva. They inflate, get erect, and fill with blood. They’re made of the same tissue of the penis shaft, and when you orgasm, the blood drains, just like with a boner. And if you don’t orgasm, they take a few hours to drain.

So it’s kind of the same idea behind “blue balls,” except it’s “blue bulbs’?”

Zoe: Jackie really doesn’t want me to use the term “blue balls,” because it’s not a real scientific concept, it’s a made up thing that men use for sexual coercion, but yeah, we kind of get “blue bulbs.” It’s like being left with a boner.

What are some of the most common and outrageous misconceptions about sexual health that you’ve encountered in your research?

Zoe: People think that discharge is gross and dirty, but it’s the way that your vagina cleans itself. Douches are terrible for you. Walgreens and CVS still sell douches, but they completely disturb your body’s ecosystem. Not necessary. I definitely wasn’t told in sex ed not to wash the inside of my vagina with soap, so I think I washed the inside of my vagina with soap for like ten years. I thought I was just washing myself. Also, talcum powder causes cervical cancer. It should not be used on pussies at all.

Have you gotten any backlash to this project? If this project does go mainstream and certain press and critics start to push back, what’s the action plan to spread the education?

Zoe: There are people that turned red in the face and got uncomfortable when we showed them this project. Just mentioning the female anatomy still makes people uncomfortable, because it’s still taboo, and that’s fucking nuts. It’s 2018. It’s so silly.

I don’t think press and critics can stop this project from spreading. Explaining this project almost never has to go beyond “it’s an online encyclopedia of the vagina” for people to immediately recognize the need. I don’t think any op-ed could convince women they don’t need to know more about their vaginas. And whatever they say, who doesn’t want to look at a 3D pussy? We’ve only received ONE negative reaction through this entire process and it was from a liberal white cis dude who told us it had “nothing to do with real feminism.” Responding to that email was one of the most fun emails I’ve ever written, so I ain’t mad. But basically it’s just been this overwhelming collective ‘Duh.’ Who knows, maybe I’ll get blindsided. My only plan is to be transparent about our process and publicly accountable when we make mistakes which of course we will. But I really doubt that we will get significant pushback.

I’m serious when I say that 2018 is the year of the pussy. People I would never say pussy around usually are taking this project completely seriously when I explain it. People maybe get uncomfortable for a second, but then you see them rise to the occasion. People are recognizing that this needs to happen, and needs to happen now. That said, I am dumbfounded that Moira Donegan got fired from The New Republic for making the Shitty Men in Media list when an anonymous outlet is so desperately needed. And that seems obvious to me too. And maybe I live in a bubble and shouldn’t take any of this for granted.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.