#MeToo

Uma, You’re Still My Hero

The men behind 'Kill Bill' abused and manipulated its star. But Uma Thurman deserves our awe and respect not only for her brilliance onscreen, but her courage off it.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

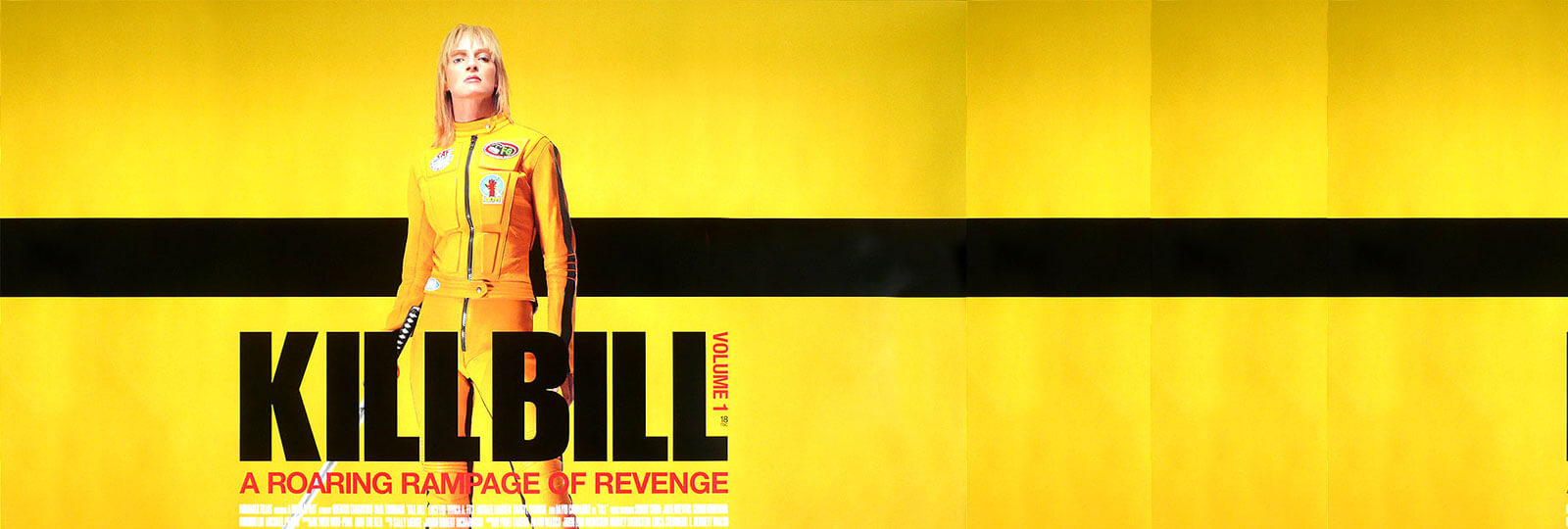

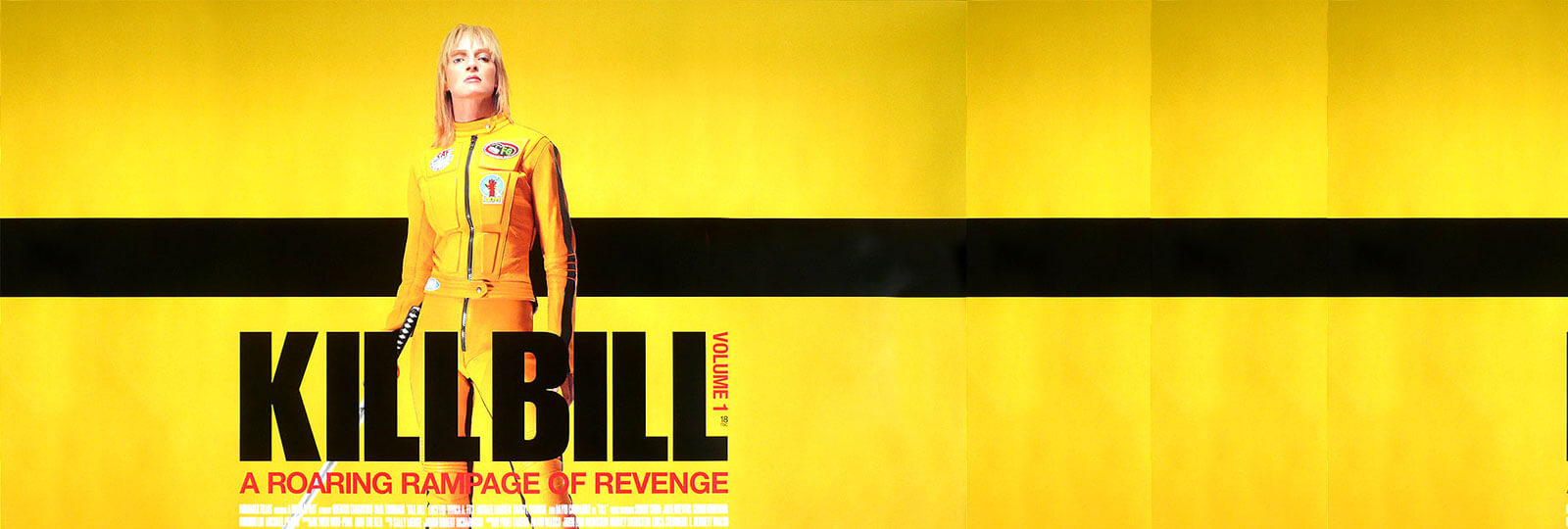

For almost two decades, one of the most resonant images of an empowered woman for me was Uma Thurman as Beatrix Kiddo, a.k.a. Black Mamba, a.k.a. the Bride, monologuing behind the wheel of a convertible. She speaks in a low, slow voice that thrums with rage—and a note of “bloody satisfaction” at all the people she’s killed in “what the movie advertisements refer to as ‘a roaring rampage of revenge’”—as she describes “the last one, the one I’m driving to now. The only one left. And when I arrive at my destination, I am gonna kill Bill.” The path to her destination—face to face with her ex-boss and ex-lover, the man who helped her become one of the deadliest women in the world, the father of her child, the smirking killer who shot her in the head as she moaned for mercy and told her that this was him “at [his] most masochistic”—is cobblestoned with agony. She has been shot; raped; cut up and bruised in battle; bound and buried alive—but she has slashed and punched and kicked and knuckled her way out six feet of dirt to take her final revenge. Because she deserves it, goddamn it.

The Kill Bill movies came out just as I was graduating college, and I’d never seen anything like them, or like the woman they featured, a heroine so naked in her rage, and so deadly capable of inflicting it upon the rat bastards who deserved it. Here was a cinematic universe centered so explicitly around women—even Beatrix’s core nemeses, the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad, comprised mostly women with their own rich histories: Vernita Green, a.k.a. Copperhead (Vivica A. Fox); O-Ren Ishii, a.k.a. Cottonmouth (Lucy Liu); and Elle Driver, a.k.a. California Mountain Snake (Daryl Hannah). In the first film, O-Ren—“half-Chinese, half-Japanese, half-American”—is treated as a “final boss,” complete with her own origin story anime sequence, and a last battle with Beatrix that is elegant and raw, brutal and poignant. Most of the other action heroines I’d seen—including the godmother of them all, Sigourney Weaver’s alien-killing Ellen Ripley—were surrounded by men (if they weren’t explicitly in service of a man’s story). But here was a pastiche of all the genre films I used to sneak down to watch on late-late-night cable—the Bruce Lee flicks and the grindhouse fare, the revenge thrillers and the spaghetti Westerns—finally rendered through a woman-centered story.

For years, Kill Bill has been the Alpha and the Omega of my creative impulses: The films, and particularly Uma Thurman’s performance, formed the crux of my writerly obsessions. In fiction and nonfiction, I’ve devoted myself to the alchemy of heroines; I write about the grit and complexities of “strong female protagonists,” especially the emotionally ugly, angrier ones. Thurman is a marvel of violence and vulnerability; her Beatrix feels like a carnivorous plant, scarred, and burned by an arid terrain, but still verdant and sensate, parting her fanged leaves as the flies circle low. Clearly, I am not alone in being influenced by Kill Bill, or by the incipient hipster feminism (or feminism-adjacent) strands in Quentin Tarantino’s earlier work (Hell, even the CW teen soap Riverdale features a tribute to the finale of Death Proof, where the quartet of heroines stomps the woman-killing villain Stuntman Mike to death). Yet, a recent New York Times profile of Thurman indelibly complicates, and in some instances, further illuminates, Kill Bill’s position as a seminal piece of feminist (or, at least feminist-adjacent) piece of pop culture.

The profile, penned by Maureen Dowd, is the inevitable, elongated, and positively wrenching follow-up to Thurman’s infamous late-2017 red-carpet interview. When asked about Harvey Weinstein, who produced the Kill Bill movies (as well as Pulp Fiction), and the importance of women speaking out against workplace abuse and assault, Thurman becomes a tightly coiled spring: “I don’t have a tidy soundbite for you, because I’ve learned … I am not a child, and I’ve learned that, when I’ve spoken in anger, I usually regret the way I express myself. So, I’ve been waiting to feel less angry. And when I’m ready I’ll say what I have to say.” What she has to say is nothing less than gutting: Weinstein sexually assaulted her. And it happened more than once. In a particularly disturbing detail, after one hotel room encounter where she tried to confront him about “the first attack,” she emerged blank and disheveled, unable to remember what happened.

She also reveals that Tarantino, the same man who wrote the “roaring rampage of revenge” speech, who crafted a world where women can literally make their abusers’ hearts stop with one five-point punch, is a craven sadist—and had spat in her face for a scene, strangled her with a chain mace for another; and, most devastatingly, bullied her into driving a stunt car that the on-set teamsters deemed unsafe, until she wrecked, and was wrecked, for life, with a concussion and lasting knee and neck injuries (and the trauma of believing, in the moments immediately afterward, that she’d never walk again). All so he could get a shot of her hair billowing in a certain way.

These revelations about Tarantino emerge at a time where the twinned emphasis on harassment and abuse and on women’s righteous anger holds a blade of Hanzo steel to the pretty little throat of auteur mythos. The age-old debate about separating the art from the artist that had, until now, been occasionally sparked by a reminder that Woody Allen, Patron Saint of All Film Bros and their Cult of “Well Actually,” is credibly accused of sexually molesting his young daughter, has attained a new urgency.

There’s a clearer understanding that the worshipfulness that turns a man into a god among creatives also creates a smokescreen of ceremonial incense for his abuses—and a greater willingness to call out our idols. But what makes Tarantino’s abuse of Thurman feel especially galling is that he did it, all of it, while making a movie about a violated woman who roars, and rampages, and gets bloody satisfaction against her transgressors—a woman who would become a truly iconic, even inspirational, film heroine. Now, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve seen some traces of subtle (and not-so-subtle) misogyny in the films—most notably, the way that every man that Beatrix encounters comments on her attractiveness and fuckability (with the lone exception of Pai Mei, whose “cruel tutelage,” turns her into a top assassin); or the fact that, while Beatrix killing Buck (the orderly who “likes to fuck”) is a fist-pump of a moment, it was wholly unnecessary to include her being raped, repeatedly, while comatose.

I suppose I viewed these tropes as a contemporary re-mix of the exploitation genre, particularly the rape-revenge sub-genre, that gave Kill Bill its spiritual grist. Exploitation films often inflict extreme sexual violence upon their heroines, so that their revenge can be appropriately oversize—and they can act with a justifiable savagery that is otherwise never permitted in women. In the 2010 thriller, I Spit on Your Grave, for instance, the rape survivor, on her roaring rampage of revenge, tricks her attackers by pretending to seduce them before she dispatches them in deliciously grisly ways—like hanging them, slicing their dicks off mid-hand job, or disemboweling them with a speedboat. In this regard, the heroine isn’t just battling against the damn dirty bastards who did her wrong; she’s engaged in a meta-textual war against the misogynist culture outside of the film itself. But now, knowing that Tarantino was profoundly abusive to a woman who was supposedly his creative collaborator, it’s hard not to see this smirking misogyny for what it really is—another damn dirty bastard getting his rocks off on a woman’s suffering. And this knowledge contextualizes the woman-hating ugliness of Django Unchained—where Tarantino not only reduced Kerry Washington, one of our great working actresses, to a damsel-in-distress trope; he also tortured her on set—and The Hateful Eight, in which Jennifer Jason Leigh is repeatedly beaten by men, and which remains one of the most deeply uncomfortable experiences I’ve ever had in a movie theater.

So, what do I do with Kill Bill? How can I reconcile the truth that the movie most responsible for my early vision of an empowered, and compelling, heroine—and my “pop culture feminism,” if you will—was produced by a serial rapist and harasser, and conceived of, in part, by a man who bullied his star into permanent injuries? To redeem the whole bloody affair, I must separate the “Quentin of it all” from the “Uma of it all.” After all, the closing credits mention that the movies are “based on the character of ‘the Bride,’ created by Q & U”—although the auteur worship that has elevated the Q into a solitary genius has erased the U from her own creation. While they were collaborating on Pulp Fiction, Thurman told Tarantino about her idea for a character named Beatrix, a character who could align with his loose ideas on a revenge story starring the deadliest woman in the world. The two engaged in an intense two-week dialogue about the character—and the film’s iconic opening, that close-up on the blood-spattered bride, was all Thurman’s idea. “It took me a year and a half to write the script and I spent that year and a half hanging out with Uma,” Tarantino would say. “We were just doing it together … she was reading it and we’re talking about it.”

If our knowledge about Weinstein, and about Tarantino, diminishes our appreciation of their contributions to the movie, then that knowledge must, conversely, renew our awe for Thurman’s artistry. She channeled the agony of being so horribly betrayed by men she considered mentors and collaborators into a character who is also betrayed by the man she loved the most. In the Times interview, Thurman describes the car accident as “dehumanization to the point of death,” and laments that, “I went from being a creative contributor and performer to being like a broken tool.” So, it is especially important—a political act, in a way; certainly, an act of solidarity—to remember, and respect, Thurman as a collaborator, an architect of a cinematic experience that still inspires so many people. It’s telling that, after Thurman’s initial red-carpet interview, the internet erupted in GIFs of Beatrix slicing through the Crazy 88 or training with Pai Mei. Uma was done wrong by the industry, by the men she trusted, and even by the profile itself, which Dowd treats as just another dishy celeb profile, complete with references to Thurman vaping, drinking white wine, and feeding pizza boxes into the fireplace. One wishes that Thurman’s story had been entrusted with a real reporter with real experience writing about abuse and assault, like Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, who first broke the Weinstein story.

When Beatrix finally sits across from Bill, for a final confrontation that is more brutal for its intimacy, she tells him, somewhat wistfully, somewhat angrily: “If I had to make a list of impossible things that would never happen, you performing a coup de grace on me, by busting a cap in my crown, would have been right at the top of the list. But I’d be wrong, wouldn’t I?” In a meta-textual way, here is Thurman, a woman wronged, speaking to the man across from her, but also to the man behind the camera, the supposed friend who irrevocably harmed her. Now, of course, I must view Kill Bill through the prism of the abusive, sexist culture it was made in (and I’m not exactly advance-purchasing my tickets to Tarantino’s forthcoming Manson-era flick). But I must also view the film through the prism of Thurman’s incredible, formidable survival. Thurman turns a character who, on paper, could have been an inscrutable, Terminator-esque bad-ass, into a killer who is raw with regret, who grieves the wrongs that were done to her, though she is amply capable of avenging it. She endures as a symbol of women’s power and anger, and ultimate triumph over victimization, because of everything Thurman has instilled in her.

My love of Kill Bill exists in a new paradigm, one that centers on Uma Thurman’s indelible contributions to cinema history, and, in a clearly much smaller way, my own maturation as an artist. And if I could say one thing to her, other than I’m so sorry, it would be that she was never a broken tool, that she was always so much more than what these men tried to reduce her to. She was, then, and is now, a kinetic force of power and rage, wry wit and an unconquerable strength.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.