Whitewashing

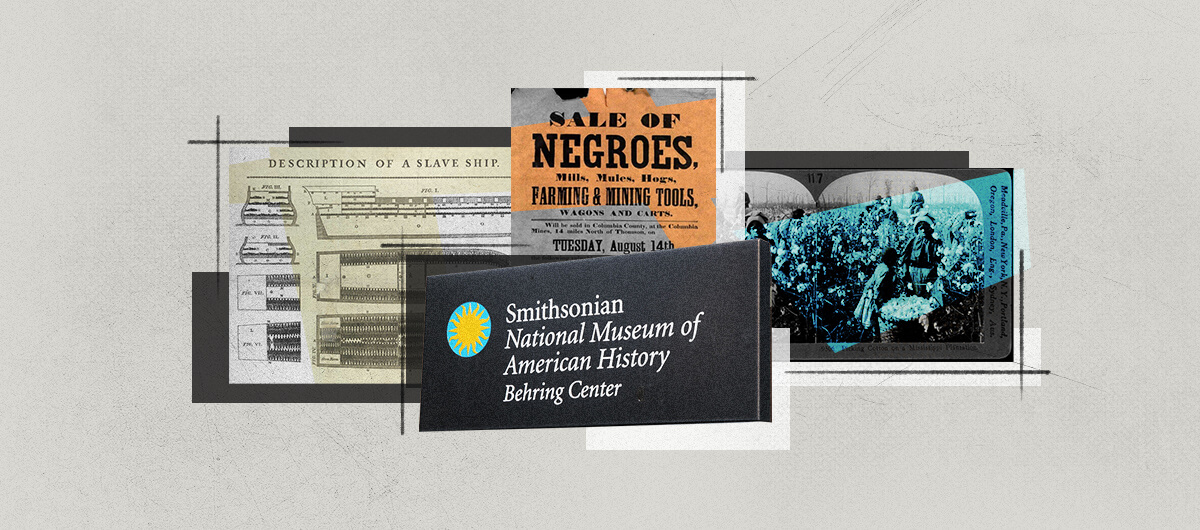

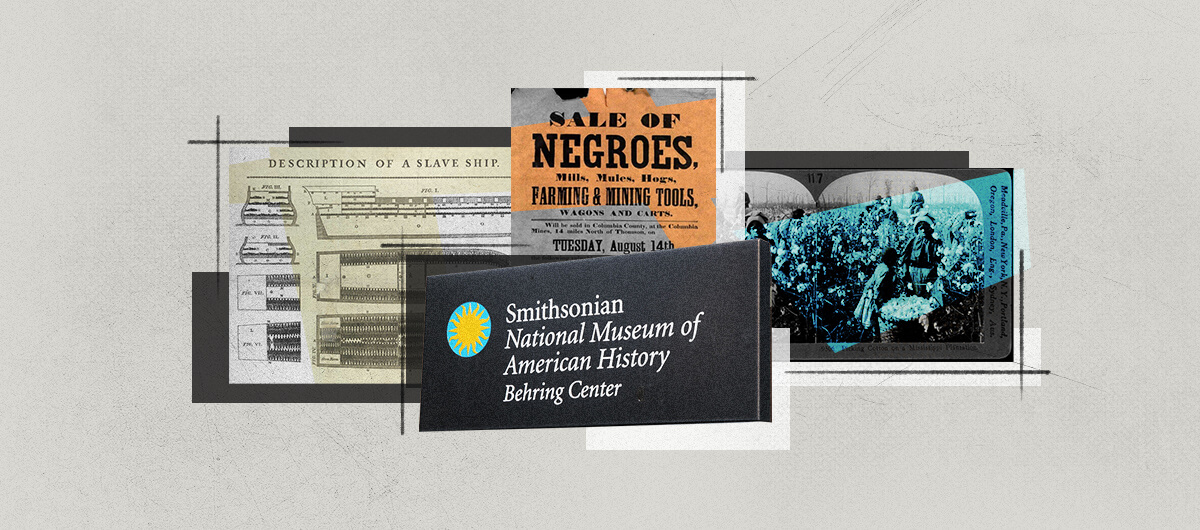

The History of Slavery Cannot Be Erased

With Trump raging against the Smithsonian Museum, it's clear that his authoritarian goals are to create a false, perfect past because a functional democracy demands historical honesty.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Last week, the White House sent this “Letter to the Smithsonian,” their latest missive addressed to one of our cultural institutions with their demands to whitewash history. It is likely not going to be Trump’s final word on trying to promote a shiny, happy, mythological vision of our past, in this instance, our nation’s history of slavery. Here’s what he said later this week on Truth Social:

The Museums throughout Washington, but all over the Country are, essentially, the last remaining segment of “WOKE.” The Smithsonian is OUT OF CONTROL, where everything discussed is how horrible our Country is, how bad Slavery was, and how unaccomplished the downtrodden have been — Nothing about Success, nothing about Brightness, nothing about the Future. We are not going to allow this to happen, and I have instructed my attorneys to go through the Museums, and start the exact same process that has been done with Colleges and Universities where tremendous progress has been made. This Country cannot be WOKE, because WOKE IS BROKE. We have the “HOTTEST” Country in the World, and we want people to talk about it, including in our Museums.

In late March, Trump issued a noxious executive order called “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History” directed at the Smithsonian, among other American institutions. And now, in another horrific blow, the President is raging against the Smithsonian for discussing … “how bad Slavery was.” That’s what “woke” means: being clear on the actual, genuine, unending horror that was slavery.

I guess, at least, he’s being open about what I’ve spent the year writing about, his manipulation of history — he doesn’t want us to ever mention how bad slavery was. That’s why they’re putting back up Confederate memorials. That’s why his people are pushing PragerU, a conservative media organization that is promoting itself as an educational network. That’s why they’re pulling down Black military heroes from government websites. The anger, the resentment about the way the humanities engage with the flawed project that is America, all boils down to this: Trump and the MAGA right do not want to be confronted with the violence of slavery, and its fundamental role in American history, culture, art, economics, and identity.

As historian Taulby Edmondson has pointed out, it is, unfortunately, rare that any of our institutions offer comprehensive coverage of what slavery actually was in the United States. He singles out two who do: the Smithsonian and the Whitney Plantation. Behind Trump’s yelling at the Smithsonian is the same fantasy that’s destroying universities, mandating white supremacist history: a vision of a fascist America, the mythohistory and nostalgia that bolsters the White Christian Nation his followers fantasize about. And nothing shatters that paternalistic, Lost Cause–esque, Jim Crow–era White feel-good racism like actually dealing with slavery. Because “how bad Slavery was” is worse. Much worse. Worse than you imagine, worse than you learn, worse than even the museums can depict.

At the forts where many ships picked up captives for transfer across the Atlantic, slave traders tried to calculate precisely how little they could feed captives without losing profits by starving them to death, in what historian Stephanie Smallwood has called a “rationalized science of human deprivation.” A number of slaves died in the 1690s because Royal African Company agents bought cheap, soft stones for grinding corn — desperate captives were forced by their hunger to eat sand, effectively, until it killed them.

The ships were even worse. Captains mad with drink, opioids, and malaria sexually assaulted enslaved women, beat their own crew members to death, and rushed across the ocean to sell their cargo before smallpox and starvation could deplete their profits. An enslaved man named Boyrereau Brinch later reported that even the wailing of starving children “could not penetrate the heart” of the ship’s captain, not even enough for him to “bestow a morsel of bread upon his infant captive, even enough to save his life.”

Those who survived the Middle Passage had to endure new horrors. After a five-month voyage, the 300-odd surviving captives aboard Brinch’s ship were brought aboard in Barbados in 1757. While the ship’s captain waited to sell them, they were chained together and set to work picking apart harsh hemp rope into a sealing material known as oakum. The rough rope lacerated their hands. One of them, a man named Syneyo, gave a long and memorable speech railing against his enslaver, which Brinch remembered in detail many years later. It culminated in a plea: “If you have one spark of human sensibility, or even the least shade of humanity, repent and let us … return to our once happy shores.”

After he spoke, “all was silent for a few minutes” until the captain replied. He insulted Syneyo, promised to cut his rations to “twelve kernels of corn per day,” and to make his breakfast 50 lashes with a whip. To silence Africans’ cries of agony, slave traders sometimes gagged them with oakum. PragerU’s ventriloquized Columbus insists that slavery was better than death. Countless Africans who jumped to their deaths in the Atlantic or took their own lives rather than live in slavery tell us otherwise.

Sellers took pains to disguise dead and dying captives as healthy workers, hoping they might survive at least a few weeks so they could be sold. Sometimes slave traders sealed the orifices of enslaved Africans using oakum to cover up dysentery. South Carolina shoemaker Patrick Hind tried to profit by buying one half-dead boy or man in 1757, hoping to provide medical care and then sell him as a healthier worker; when this failed because of disability or illness, Hind’s friend Henry Laurens called the unnamed captive a “loathsome carcass” and an “idiot,” and bemoaned Hind’s financial rather than the enslaved child’s suffering. Plantation owners hoped Africans would last longer — years rather than weeks — but expected to work most of them to death within a few years. When overseer Mr. Pooley killed 14 people on Samuel Martin’s Antiguan estate out of sheer neglect, Martin merely scolded him before offering him a recommendation for another overseer job elsewhere.

Nineteenth-century mortality was lower: Cotton was less deadly than sugar, and the post-1808 ban on the slave trade made it harder to treat enslaved workers as expendable. This meant that Black Americans were born, lived their entire lives, and died shifting through backbreaking labor. Overseers on cotton plantations set ever-rising productivity quotas. Those who failed to meet them were whipped in proportion to how short they fell. Enslaved people who worked outside of plantations also faced constant brutality. When an enslaved man named Lewis, whose enslaver Mr. Broadwell was a merchant in 19th-century New Orleans, tried to visit his wife at the plantation a few miles from the city she had been sold to, Broadwell tortured Lewis by having him tied to a beam with only his toes touching the floor to keep him from asphyxiating.

Sexual violence was a constant in Atlantic slavery, from slave ships on the African coast to plantations in Virginia. Eighteenth-century Jamaican planter Thomas Thistlewood committed thousands of sexual assaults, and recorded them in his diaries as an ordinary daily event, without any shame. Thistlewood, like other planters, sadistically tortured enslaved people to punish them for resistance: One of his methods was having them whipped, having acidic liquid rubbed into their wounds, forcing another enslaved person to defecate in their mouth, and then gagging them. Ellen Sinclair, who was born into slavery, recalled her mother telling her that one could see which women had resisted Bill Anderson or his sons on his plantation in antebellum Texas, because they were scarred from the whip. William Craft, an abolitionist who had escaped slavery, explains that “a slave [had] no higher appeal than the mere will of her master.”

Museums like the Smithsonian, and historians of slavery, do far more than just tell us how brutal slavery was. They also show us how enslaved people survived and resisted slavery — how they took care of each other and tried to free themselves despite constant violence. Even the most mundane records of daily violence also contain moments of resistance, records like an advertisement that an Antiguan enslaver took out in 1798, offering a reward for the return of a woman known as Louisa. As an identifying detail, he reported that she laughed often when spoken to. She might have been one of the numerous enslaved Antiguans who conspired to help fugitives escape slavery aboard Navy warships, or she might simply have been a woman who survived and occasionally managed to laugh despite unspeakable horrors.

America’s very founding cannot be understood without enslaved people. Enslaved maritime workers in Newport, Rhode Island, were critical participants in the proto-revolutionary riots of the 1760s. For them, this was not a tax revolt but a revolt against imperial policing. Rhode Island’s John Quamine, who bought his freedom with lottery winnings, fought as a revolutionary privateer to earn the money to free his family. He died, a casualty of war, in 1779. But his efforts organizing Black Rhode Islanders helped pave the way for the state’s abolition of slavery. Trump’s war on museums threatens to bury stories of resistance as well as suffering; of life as well as death.

The way we talk about slavery, it’s like one day, virtuous White Americans stood up and fought a war against someone else — that the Confederacy was something other than half of the United States — and ended it. We still discuss the horror and the violence against Black people as if it is the past. As much as Trump is commenting specifically on the discussion of slavery, and wanting us to forget it, the unending violence against Black Americans did not stop in 1865, and still hasn’t stopped. If you read any account of slavery — a diary from a racist plantation overseer, letters from a plantation owner, any of the accounts of enslaved people — then John Brown’s holy war against slaveowners makes sense. Sherman’s March to the Sea is a reasonable response. Reconstruction did not go far enough.

The Klan Act — the Enforcement Act of 1871 that authorized the president to deploy troops against the first Klan — should have been applied fully and forever. We have to actually talk about what it means for Jim Crow to valorize the Lost Cause and erect the Confederate statues Trump’s administration loves, and then discuss mass lynchings, the casual photography of towns in their Sunday best posing with tier murder victims. We have to talk about the massacres in Atlanta, the Red Summer of 1919 — Washington, Norfolk, Chicago, Omaha, Elaine, and Wilmington — and Ocoee, Tulsa, Perry, and Rosewood. We have to talk about the Second Klan marching in D.C. under the America First banner. We have to talk about the violence, murders, bombings, lynching, and abuse targeted against the Civil Right Movement activists — the MOVE bombing, the murders of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark and Bobby Hutton — not just recite “I Have A Dream” in classrooms out of context and preach nonviolence.

We have to acknowledge the murders — by cops and by vigilantes who got away with it — and know the names of Daunte Wright. Andre Hill. Manuel Ellis. Rayshard Brooks. Daniel Prude. George Floyd. Trayvon Martin. Breonna Taylor. Atatiana Jefferson. Aura Rosser. Stephon Clark. Botham Jean. Philando Castile. Alton Sterling. Freddie Gray. Janisha Fonville. Eric Garner. Michelle Cusseaux. Akai Gurley. Gabriella Navarez. Tamir Rice. Michael Brown. Tanisha Anderson. And so many others.

And never forget that the man sitting in the Oval Office took out a full-page advertisement in the New York Times calling for the execution of the Central Park Five; profited from far-right panic over Black Lives Matter marches; routinely dehumanizes people of color, wields “DEI” as an acronym of white panic and uses it to enforce discrimination against minorities, and was sued by the Justice Department in the 1970s for racial discrimination. Trump would like us to stop talking about “how bad Slavery was” so we will stop talking about everything that came after, too.

This is America, the land of the free. But that freedom has never been universal, it has always been contested, and it has been fought over and fought for: Blood has been spilled, endlessly, on plantation grounds and battlefields, city streets and empty fields, in search of something better and more than what we have been. Trump wants to deny this. Fascism demands a false past of perfection that we can return to if only we kill the right people. Democracy demands reckoning. Truth. Reconciliation, if you can achieve it. And a forward momentum to someday become more. Become a place where we can hold these truths to be genuinely self evident, that all people have the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And that too will be a fight, one we must win.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.