activism

How Young Activists Are Getting India To Talk About Menstruation

From a marathon runner who let it bleed to “Pads Against Sexism,” feminists are raising desperately needed awareness about that time of the month.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

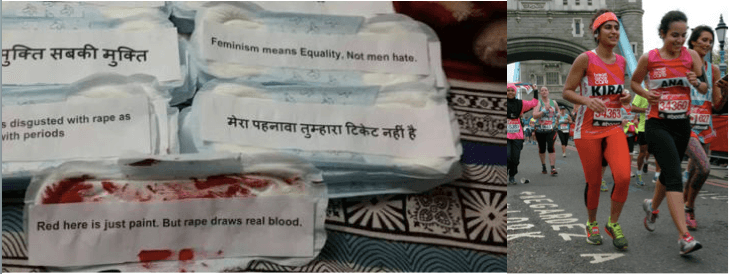

Kiran Gandhi, the 26-year-old drummer for M.I.A. and Harvard Business graduate, has been in the news a lot recently for choosing to menstruate without a pad or a tampon during the London marathon back in April, which she revealed in a now-viral essay for Medium and blog post. She did it, she said, “to draw light to my sisters who don’t have access to tampons and … hide it away like it doesn’t exist.” And though she’s had some defenders on social media who appreciate the boldness of speaking out against period-shaming (“badass”; “radical”), there are men and women in the U.K. and in the U.S. even all these months later still recoiling in horror, declaring it “disgusting” and “TMI.”

But perhaps they don’t appreciate the fact that menstruation is a major source of shame for women in India, many of whom don’t learn about it until their periods begin. Or that of the 355 million menstruating women in India, only 12 percent of them use some sort of sanitary method to stem the blood flow. Or that only about 31 percent households in rural parts of the country have toilets, which becomes even more burdensome for women who need to dispose of feminine hygiene projects. Most public toilets don’t even have wastebaskets for women to dispose of pads. Furthermore, when women venture out to defecate in the open, they expose themselves not only to the threat of disease, but of sexual violence.

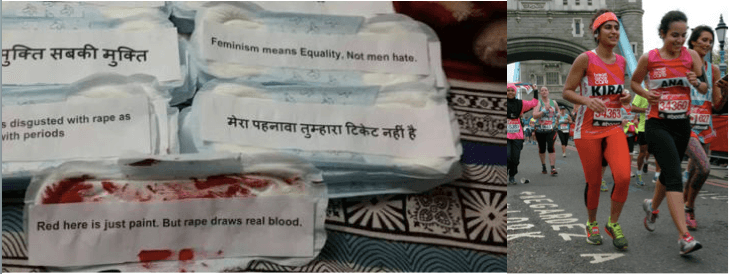

Which is why a group of psychology undergrads at Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi, inspired by an initiative called “Pads Against Sexism” created by a student in Germany named Elona Kastratia, began their own chapter. Delhi’s Pads Against Sexism took to the capital’s streets back in March, plastering walls around town with sanitary pads with feminist messages about everything from periods to rape.

The pads were inscribed with sayings like (note: translated here into English): “I’m not going to stay indoors because you’re horny.” Another one is like the Indian rebuke of “She’s asking for it”: “I’m not going to change the way I dress; why don’t you change your attitude instead.”

The students would approach people in town, in one instance, a group of auto-rickshaw drivers at a Metro station and quizzed them about menstruation. “We asked them if they knew what this (pad) was,” said Kaainat Khan, one of the leaders of the Delhi chapter of Pads Against Sexism. (They did.)

“The entire concept behind Pads Against Sexism is if you are going to suppress a woman at a certain time in life, you suppress the whole gender,” said Khan. The objective is to attack the country’s deep-seated misogyny, which is not only source of the widespread menstrual taboos, but of the rape culture, because, as Khan explained, “when you suppress the whole gender, you give rise to a culture of rape.”

In patriarchal India, women don’t get a level-playing field. Female literacy is much lower at 65 percent, compared to 82 percent for men. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, 92 women are raped in the country every day. But in a repressive society such as India’s, issues such as rape, and even sex and reproductive health are simply not discussed, or even mentioned. “People are ashamed to talk about it,” said Aditi Gupta, founder of Menstrupedia, a comic book and website devoted to menstruation. It’s not uncommon for teachers at Indian schools to skip chapters related to reproductive health, she added. Many boys don’t even learn about menstruation until college—and often through their girlfriends.

And because of this climate of ignorance, myths and misinformation is easily perpetuated and disseminated: In both urban and rural areas, young girls are asked to avoid touching pickles when they are menstruating because of the belief that the pickle might be spoiled. They are also asked to stay away from areas of worship during this time because that could invite the gods’ wrath.

Period shame isn’t exclusive to India, of course. In Nepal, women in rural areas are sent to separate huts or cowsheds. Orthodox Jews regard a woman unclean both during the week of and the week after her period. Even the social-media platform Instagram recently took down pictures that showed a woman sleeping in blood-stained pajamas. Judging from the comments that Gandhi received from the American press after her interview with Cosmopolitan.com, both men and women remain squeamish about menstruation (e.g., “Gross, I’m a woman and that’s just unsanitary”; “I love how Cosmo is making her out to be the Rosa Parks of bleeding on your leggings”).

Another issue for women in India is access: 68 percent of rural women can’t afford sanitary napkins, according to an AC Nielsen study (compare this to China, where the majority of women use them), and approximately 23 percent of rural adolescent girls between the ages of 12 to 18 drop out of school due to a lack of sanitary facilities. What do women use when they can’t get sanitary napkins? According to the study: most frequently they use, and reuse cloth, but some women have been known to use sand, husk, and even ash. In fact, 45 percent of women reuse cloth and 70 percent dry them in the shade, which increases chances of infections like Reproductive Tract Infection (RTI).

Despite the bleak scenario, things would appear to be slowly changing in India, with an emerging feminist awakening through enterprising men and women across the country, who have initiated campaigns to produce cheap sanitary pads in rural areas. For example, Coimbatore-based entrepreneur Arunachalam Muruganantham developed a low-cost method of creating sanitary pads. His machine is installed across 27 states in India and seven other countries. He supplies these cheap pads to women through non-profits and self-help groups. And last year, Gupta, together with artist and storyteller Tuhin Paul, who are based in the western Indian city of Ahmedabad launched Menstrupedia. The comic book, which initially began as Gupta’s dissertation, explains the science behind menstruation through four female characters. The accompanying website receives 100,000 visitors a month from around 200 countries. They have sold 6,000 comic books worldwide so far.

Ordinary women have also risen to the challenge. When more than 40 women were strip-searched in a Kerala factory late last year because one of employee had left a sanitary napkin in the toilet, female protestors launched the “Red Alert” campaign, and sent sanitary napkins to the factory owners.

Kavita Krishnan, one of India’s leading feminist activists, said, “It’s great that people have started openly talking about breaking the taboo around menstruation and that strong demands are being made by women, especially those with a poor background, to have access to menstrual hygiene.”

In the meantime, Pads Against Sexism has since slowly spread into big and small towns across the states of West Bengal, Kerala, and Karnataka.

The young campaigners seem to have matured quickly as well. Now in the second phase of the campaign, the activists want to do more meaningful work. Deepti Sharma, a student-activist, who has been involved with the campaign at Delhi University, said that their sensationalist approach got them attention initially, but it’s time to move beyond pads. “It’s a complicated message,” said Sharma. “Sometimes when you write it on pads, people don’t get it.”

Pads are also expensive. Sharma said they faced criticism that these pads should be donated instead of being squandered. Khan said they will use paper cutouts in the shape of sanitary pads—they’re cheaper and still have the visual image of the pad.

In the next stage of the movement, campaigners from different colleges will join forces to organize workshops on menstruation and reproductive health. They are sourcing stories from women about menstruation, and plan to publish a booklet that could be distributed as supplementary material at these workshops.

The question now is: Can a movement run by amateurs survive? The Delhi chapter is reaching out to non-government organizations. Parterning with them could provide Pads Against Sexism with a professional edge.

Can they bring about real impact? Gupta said they have already made a difference by bringing a hidden issue out in public consciousness. “Campaigns like Pads Against Sexism are driving people out of their comfort zone and forcing them to talk about menstruation,” said Gupta. “They may grow bigger or not, but they have done their job already.”

For Khan and her friends, the campaign started as a labor of love, but now it’s become a mission. Khan reckons campaigns such as these will eventually uproot misogyny in the country. “The more we talk about these issues, the more normal they will become,” said Khan. “And that’s how you shoot down a culture of rape that’s creeping in.”

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.