Abortion

Abortion Doctors Aren’t Retiring Because of “Stigma”

A growing lack of providers poses an alarming threat to the procedure’s safe and legal access. But the reasons behind this shortage aren’t what abortion opponents want you to believe.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

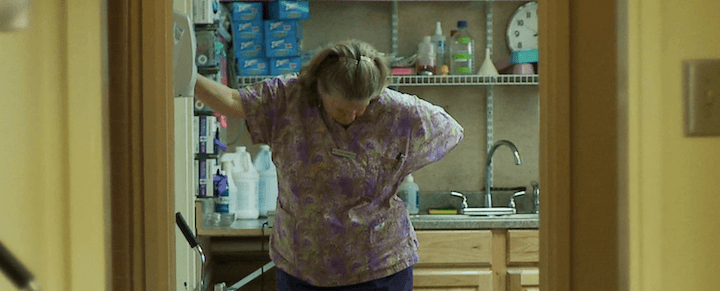

There’s a moment in After Tiller, the 2013 documentary on the four providers who still offer third-trimester abortion services after the murder of Dr. George Tiller, where Dr. Susan Robinson says, “I just thought the other day, I can’t retire, my God, there aren’t enough of us.”

I thought of that scene when a Nebraska newspaper recently reported that Planned Parenthood of the Heartland reduced the days that it could offer abortion services in their clinics in Omaha and Lincoln due to the retirement of a doctor on staff. Because it was now necessary to fly in a provider from out of state, Planned Parenthood has cut the number of days that it offers abortions almost in half, from eight per month to just five.

“It has been challenging to meet the need for abortion services at our Nebraska health centers,” Angie Remington, public-relations manager of Planned Parenthood of the Heartland told the World Herald. “We are booking out two weeks in advance.”

Doctor retirements have long been the looming crisis when it comes to abortion access, and it’s one that may be getting worse. A generation of doctors who began terminating pregnancies because they saw the effects of illegal, unsafe abortions or because they knew someone who underwent an illegal procedure is growing older, and the following generation of medical professionals—born at a time when legal, accessible abortion services were considered a given—aren’t as likely to be motivated to offer abortions with the same zeal.

According to anti-abortion activists, it’s the stigma of being a doctor who provides abortions that is keeping so many new abortion providers from filling the pipeline. Julie Schmit-Albin, the executive director of Nebraska Right to Life, asked the World Herald, “What young medical student wants to jump into that?” She may even be right, but what abortion opponents call “stigma” others would likely refer to as intimidation, pressure and even outright harassment of current and potential abortion doctors as a means of deterring others from entering the field.

Anti-abortion activists have always known that if you eliminate providers, you eliminate access. It was the motivating factor behind most of the activities depicted in Joseph Scheidler’s Closed: 99 Ways to Stop Abortion, the 1980s handbook of anti-abortion tactics meant to stop legal abortion in the United States. Picketing doctors’ homes, non-clinic workplaces, clubs, and churches was intended to intimidate current doctors into quitting, and new medical professionals into never starting in the first place.

Today the same tactics are still being used in Huntsville, Alabama, where protesters frequently bring signs to the private practice of a doctor who also offers abortions at a separate clinic; in Ohio, where abortion opponents drive a truck with pictures of aborted fetuses and the names of targeted medical providers allowing a clinic transfer agreement to stay in place; and in California, where Survivors of the Abortion Holocaust use their “training camps” to picket local abortion providers at their homes.

“Stigma,” in other words, is just a way of saying that the harassment campaign against current providers and future providers is working.

In large, progressive metro areas like New York City, Washington, D.C., and most of California, there is unlikely to ever be a massive abortion-doctor shortage, regardless of retirements. Replacing doctors who retire or otherwise stop providing abortions in low clinic access areas is a different story. When no one in the community itself is willing to open him or herself up to the sort of harassment that many abortion providers see on a daily basis—at work and at home—that means someone from out of state must be flown in, raising costs and decreasing availability, or, even worse, that the clinic closes.

We’ve watched it happen repeatedly in the last few years. Montana at one point was considered a relatively accessible state for terminating a pregnancy, with five clinics that offered surgical abortions within its borders. Faced with health issues, Dr. Susan Wicklund closed her Livingston clinic in the fall of 2013. Less than a year later, Susan Cahill’s Kalispell clinic was destroyed, putting her out of business as well. In a mere six months, Montana’s abortion access was cut nearly in half. Until South Wind Women’s Center opened in 2013 in Wichita, Kansas, there was no place in the state other than Kansas City where a person could legally end a pregnancy after the 2009 murder of Dr. Tiller. And in Wisconsin, the doctor at the only clinic that provides abortions after 20 weeks’ gestation said nearly a year ago that he wants to retire but can’t until he finds someone else to take over. Meanwhile, the rest of the clinics in the state testified that they would not be able to handle the influx of patients if his clinic shut down.

The issue isn’t necessarily the lack of providers itself, although anti-abortion activists have tried hard to make it so. In some states, legislators passed bills making it harder to train on abortion techniques in medical schools, and the increase of religious universities and hospitals makes it far more likely for a med student to make it all the way through his or her education without ever performing abortion techniques or even interacting with someone who does them. While action groups like Medical Students for Choice work to increase training opportunities in med schools, unfortunately the states passing bills road-blocking abortion training are the same states where the provider shortages are the worst. Advocacy organizations like Provide, which focuses on abortion-provider trainings in low access states, step in help navigate that gap between abundance and need.

Many providers, once trained, may feel that entering a state with an access issue is the greatest way to make a difference by offering abortion care. Dr. Cheryl Chastine told me in March that her decision to take a job in Kansas in 2013 was because, “I felt like I had the greatest obligation to meet the greatest need.” Unsurprisingly, abortion opponents have made that even more difficult, first by creating a hostile environment that makes a doctor feel unsafe to live in the state where he or she may terminate pregnancies, then by writing admitting privileges legislation knowing hospitals are far less inclined to approve privileges for a doctor who doesn’t reside in the state in which that hospital operates.

Yes, there is a shortage of abortion providers, but the issue isn’t “stigma.” The issue is harassment of doctors, legislation limiting where they live and work, and a slew of model bills that open them up to potential felony charges if a mistake is made while terminating a pregnancy. However, it’s doubtful this new batch of deterrents will last for long. Just as a generation of providers entered the field because of the conditions they saw pre-Roe, a new generation of doctors is likely to be just as inspired by this new map where a safe, legal abortion is available only on a state-by-state basis.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.