On the writer’s travels to Italy, she discovered Trump is less like Hitler and more like the buffoonish Mussolini. Only time will tell if he and his minions face a similar comeuppance.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Before visiting the school in Amandola, a small town in Italy, my husband Pat and I meet English teacher Daniela for coffee on Piazza Risorgimento. We’re there to talk to Daniela’s 12- and 13-year-old students about writing and my mother’s escape from Nazi-occupied Austria. Our connection came through Carol, a mutual friend, who told me about eight Jewish immigrants Amandola hid during WWII — a story echoing my mother’s experience and compelling me to accept Daniela’s invitation to speak in person rather than over Zoom. Given the troubling political climate in the U.S., with its own slide toward authoritarianism, it felt like a meaningful time to step away, hoping Italy’s history might offer lessons for surviving this current moment.

The piazza is alive: men playing chess, families savoring gelato. It’s easy to imagine black shirts and Nazis marching these cobblestone streets — perhaps because, back home, ICE and the National Guard now sweep through American towns, raiding businesses, detaining immigrants. “Populations are bleeding,” Daniela observes, noting the exodus of people from small towns for work elsewhere. “There are no jobs, and people are moving to bigger towns in Germany, France, Scandinavia, Estonia, and Finland.” When I ask about America, she shakes her head: “We knew a different America.”

Laundry lines still connect neighbors. Festival posters for truffles, chestnuts, and fava beans decorate shop windows. Some places, like Amandola, seem to possess an indefinable spirit — shaped by history, landscape, and the old buildings nestled among the Sibillini mountains, where resistance fighters once hid. This town rebuilt itself after the devastating 2016 earthquake, as chronicled in Christine Toomey’s When the Mountains Dance. Living on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, which was hit by Hurricane Katrina, Pat and I know something about natural disasters, poor government response, and slow recoveries.

A block from the café, Saint Augustine church is fortified with iron bars against future quakes, inside its ceiling netted to catch falling fresco. The “incorrupt” skeleton of Anthony of Amandola, who died in 1450, rests under glass — a grisly sight, but familiar, as are the ever-present images of Mussolini. Unlike Germany, where de-Nazification took root, Italy never fully purged its fascist past. Mussolini’s ghost remains everywhere. At the Piazza dei Capitani Popolo in Ascoli Piceno, photographs of Mussolini sell alongside Pinocchio dolls with noses of varying lengths, depending on his lies.

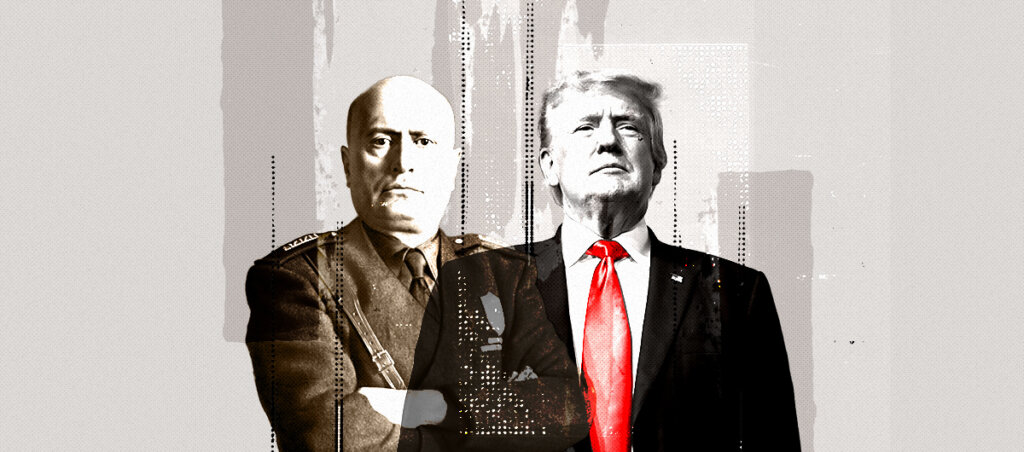

Traveling through Italy, the parallels between Mussolini and Trump become hard to ignore. Mussolini: aggressive, proud, grumpy; expelled for stabbing a classmate; a violent temper; a master of propaganda and lies; promised national renewal; used violence and intimidation; loved crowds and photo ops, often shirtless to appear virile; survived assassination attempts; fixed elections; cultivated a cult of personality; criminalized anti-fascism; shifted political allegiances. Trump mirrors these: aggressive, proud, grumpy; a violent temper; spreads conspiracy theories; promises to “make America great”; incites violence; thrives on rallies and manipulated images; survived an assassination attempt; undermines elections; leads a personality cult; criminalizes anti-fascism; shifted parties.

While Hitler remains the embodiment of evil, Mussolini is remembered as the evil buffoon.

By 1933, Amandola, like all of Italy, was firmly under fascist control. Mussolini’s “Gold for Fatherland” campaign saw blackshirts urging women to toss jewelry into military helmets, priests their crosses, to fund expansion in Africa. Prominent citizens — teachers, doctors, pharmacists — were forced into the fascist party to keep their jobs.

My mother once saw Mussolini in Rome before WWII, a short man appearing tall atop a white horse. Her tutor, a nun, assigned her to write about his glory. She focused on Ethiopia, but lacked sufficient praise, earning a low grade.

***

Amandola’s middle school, like its church, is girded against earthquakes, with a climbing wall built into the brace. The students introduce themselves in English — one loves The Godfather, most love pizza and spaghetti. I worry: Are they too young for the history I’m here to share?

Pat uses Google maps to show our home on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. The class reacts with “oh” as he zooms in on our town. Mussolini liked renaming things too, calling the Mediterranean Mare Nostrum, meaning “Our Sea.”

I tell them how honored I am to be in Amandola, a town whose history connects us. In September 1943, stationmaster Giuseppe Brutti saw eight exhausted Jewish refugees — the Almuli-Eskenazi family — at the train station: an elderly woman, her daughters and granddaughters, Ena and Alisa, aged 6 and 8, and a doctor with his family. They’d fled to Italy, only to be arrested for being Jewish, forced to report daily to police until Mussolini’s fall, then pushed further south toward the Allies.

Amandola, near Germany’s last defense line, was occupied by Nazi troops and intelligence officers — a dangerous place for Jews. Brutti invited them to dinner above the station house, then gave them cots and blankets to sleep. He knew the risk: Discovery meant death for all. The next morning, Brutti conferred with trusted townsfolk. Together, they resolved to keep the family safe, arranging housing, food, beds, and clothes despite the danger.

“I tell this to you because it only took one person to save those eight people,” I say.

Some students know this story, likely descended from those who helped. Others listen intently. Even now, retelling this history, I marvel at Brutti’s courage. He saw what needed doing and did it — helped, then rallied others to help. That’s all it took. For years, their community had been subjugated by a clownish leader and his thugs. When did they decide: “I must help”? I wonder if, in the U.S., that tipping point will come — when enough say “enough.”

Amandola didn’t unite against fascism all at once, but some came together to save lives. Maybe they’d finally had enough of lies, hate, and failed promises. After all, Mussolini hadn’t improved their lives. At one point, a cobbler denounced the Almuli-Eskenazis to the Germans, but Brutti organized their escape to San Cristoforo, southeast of Turin, where a priest sheltered them until liberation in June 1944.

Eventually, Alisa and Ena reached the U.S. In 2010, they visited Evansville, Indiana, to see Alisa’s granddaughter perform — a connection facilitated by Carol, who introduced me to their story. Daniela’s classroom displays Evansville student letters — “Dear Italy, Thank You. You’ve Got Mail” — a testament to the long-running Pen Pal program between the towns.

I show the students a picture of my mother, once their age, fleeing the Nazis in 1939. Alisa and Ena’s story resonates because my mother, too, was an immigrant needing help from strangers. I recount my mother’s journey: her escape from Vienna, her years in England, her eventual reunion with family and emigration to America. Some relatives were murdered in camps; others escaped or hid.

Watching ICE arrests and seeing the detention centers on the news shatters my faith in America. My mother warned “it will happen again.” I believed her but I never thought I’d witness such violence and hate myself. Surely, a reckoning is at hand.

Donald Trump is clearly following Mussolini’s fascist playbook, but they appear to forget how that ended.

In April 1945, the Italian resistance captured Mussolini and his mistress, shot them, then hung their dead bodies upside down from the girder of a gas station in a public square in Milan. It was a warning.

Many of Mussolini’s loyalists were dragged on the ground, then dumped alongside them, too. Crowds of people gawked and took pictures. They cut the bodies down only to beat the carcasses more, all while filming and taking more pictures.

These were the last photographs of Mussolini and his fascist regime and they are gruesome.

The violence they incited ultimately consumed them. For the first time in my life, I understand the rage of those crowds in Milan. And I am not at all comfortable with my rage, angry that the hate exuding from our current president has polluted me.

I hate all the hating, the lying, and the willful celebration of ignorance. Not to mention thoughts about revenge, too. There are times when I dream of a reset button to press to a time when most people knew right from wrong; good from evil.

When Hitler, in his bunker, heard what the people did to Mussolini, he killed himself, instructing his men to dispose of his body so that his enemies could not do what they had done to his ally.

Yet, even in dark times, some, like the Brutti family, showed heroism and compassion, and were later honored for saving lives during the war.

There will be a day when he’s no longer in office. There will be a day when he’s gone.

How will we respond to his legacy? Will he be venerated or reviled? Will we display him as a saint or will people go after his body as they did Mussolini’s? I’ve never had such thoughts about any public figure. Maybe it’s being in Italy, seeing pictures of Mussolini, and all the bones and body parts.

Late one night, in Rome, my husband says he hasn’t said Tutto bene, or “all is well,” as much as he had wanted. Maybe because we haven’t felt it. Maybe because all may not be so well. Above our hotel bed hangs a photograph of Mussolini at the opera.

We’ve learned some uncomfortable truths: Italians don’t like cheese with fish; really good extra virgin olive oil makes you cough a little; fascism and anti-heroes are running the United States.

I want to stay in the U.S., if only to fight for democracy, but I’m not sure democracy will hold for three more years. Not at this pace.

It hasn’t even been a year, and already Donald Trump — and/or Stephen Miller — has ticked through the list of signs for fascism like it’s his to-do list. And it clearly was and is: Project 2025.

I look around the room at all the bright young faces of Daniela’s students. Despite uncertainty, I find hope in teaching about kindness and resilience, urging them, as their ancestors did, to help others no matter the obstacles.

In the end, it’s simple: Be good to each other and do what you can to help.

It only takes one person.