Straight from the authoritarian playbook, Trump has turned the RNC into a hereditary dictatorship in his quest to swap out the entire GOP—and reality itself—with a murderous...

Straight from the authoritarian playbook, Trump has turned the RNC into a hereditary dictatorship in his quest to swap out the entire GOP—and reality itself—with a murderous...

Journalism is a vital part of a healthy society, and we not only need to fund and sustain it—we need to defend it. But we also need to listen to news consumers, because the media...

Nex Benedict is the most recent casualty of the conspiracy-theory-mongering by right-wing groups, who are peddling anti-LGBTQ misinformation to instill moral panic. And it is having a...

Become a member at DAME today to help support our independent reporting so we can continue to shine a light on the stories that need to be told, from perspectives that aren’t heard enough. Every dollar we receive from readers goes directly into funding our journalism.

“All men are created equal” only holds for a specific value of “all” “men” and “equal”—and white cishet male Republicans appear to be the only ones who can define the...

From bounty-hunters to “fetal personhood” bills, GOP state lawmakers are finding new ways to criminalize not only terminating pregnancies, but nearly all forms of bodily autonomy.

It’s not hyperbole to say the re-election of the former president—twice indicted, with 91 felony counts against him—will threaten the safety of the nation and the world. His...

In this exclusive excerpt from RELINQUISHED, sociologist Gretchen Sisson explains how the historical traumas of family separation have shaped contemporary adoption in the U.S.

The writer wondered why the statue elicited a strong reaction in her until she realized that everything about it—from the story behind its creation to image itself—evokes what it's...

For years, reproductive-justice activists have been warning that the GOP’s “fetal personhood” bills would endanger access to birth control and fertility treatment—especially...

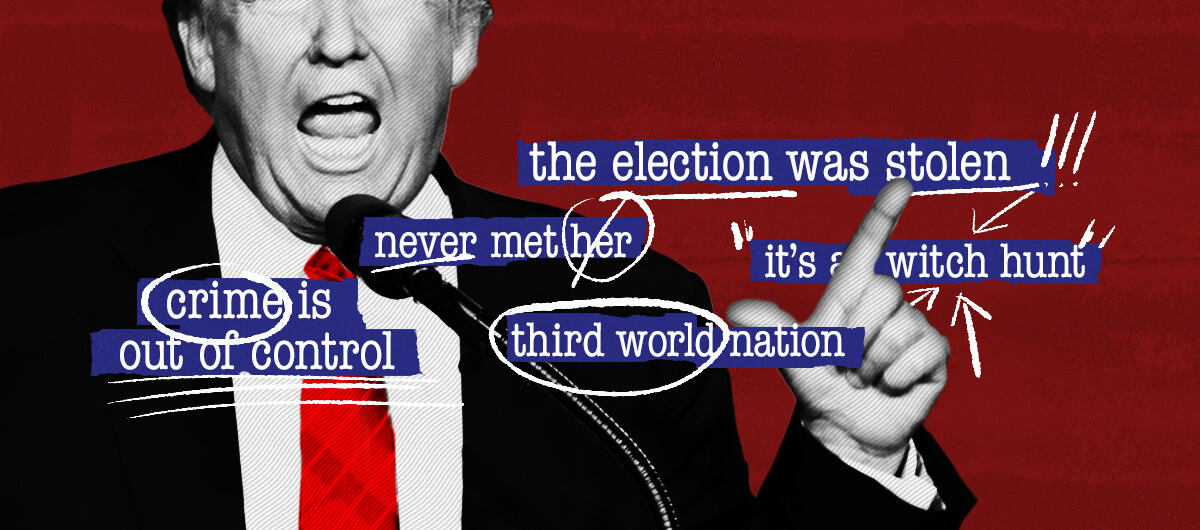

The media has normalized Trump’s extreme, outrageous statements, which has made them appear mundane—and now that coverage has the potential to help the wannabe autocrat at the...

Taking their cues from the GOP, the mainstream press has devoted their front page coverage to “but her emails”-level scandals, like President Biden’s age and DA Fani Willis’s...

Become a member at DAME today to help support our independent reporting so we can continue to shine a light on the stories that need to be told, from perspectives that aren’t heard enough. Every dollar we receive from readers goes directly into funding our journalism.

When women seek medical help for chronic pain, especially for gynecological-related issues, health providers are still scrutinizing their mental and emotional health.

When the author and her wife learned their 18-month-old needed open heart surgery, it proved to be one of the most terrifying moments of their lives—and, to their surprise, uniquely...

The author was diagnosed as autistic in her late 40s—and soon discovered she wasn’t alone. In this reported essay, she pinpoints the reasons neurodivergent cis girls elude diagnosis...

Swedish author Clara Törnvall wasn’t diagnosed with autism until she was 42. In this excerpt from ‘The Autists,’ she wonders whether the answer lies in psychiatrists’ gendered...

The long history of pool segregation: from the pre-Civil Rights Era to modern day defacto segregation

There are plenty viral news stories where people of color have been confronted in public spaces, but there’s a long history of the policing of public spaces.

Late-night pioneer Robin Thede joins Ashley to answer listeners' questions about navigating working relationships, and turning pettiness into power.

Ellevest CEO Sallie Krawcheck reminds women of the key to true gender equality: Learning to take control of our money is the only way to dismantle the patriarchy.

You don't have credit card details available. You will be redirected to update payment method page. Click OK to continue.